Soaring Oil Production Spurs Infrastructure Growth Across Booming Bakken Play

By Danny Boyd, Special Correspondent

Five years into the Williston Basin’s historic oil boom, operators and municipalities find themselves wrestling with infrastructure challenges many regions would love to face: crude oil transportation constraints brought on by surging production, and maxed-out municipal services in a rural region with a rapidly expanding population that is bursting at the seams.

Across North Dakota, demand is off the charts for everything from drilling rigs and pumping units to housing and office space, driven by a blistering pace of activity in the Bakken Shale play. The number of producing Bakken/Three Forks wells in North Dakota has expanded by more than 700 percent (from 470 to 3,377) over the past four years, and daily oil production in the state skyrocketed from 36,000 barrels in January 2008 to 481,000 barrels in January 2012–a nearly 14-fold increase!

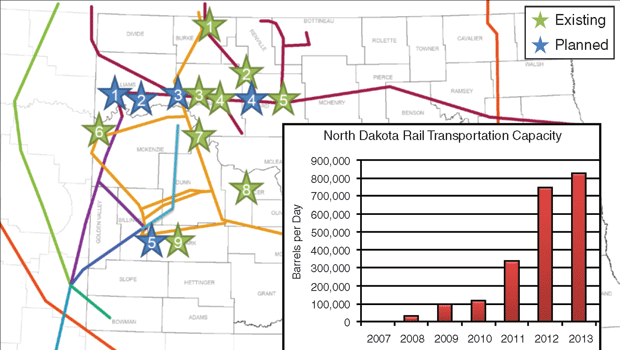

With that kind of meteoric growth, one of the most obvious and pressing needs is transportation capacity to ship the produced oil to market. To meet the need, major investments are being made in pipeline systems that could double North Dakota’s daily export capacity over the next five years, as well as in a rapidly expanding rail transport system that is expected to have a capacity of 750,000 barrels a day this year, according to Justin Kringstad, director of the North Dakota Pipeline Authority.

“Considering the incredible production increase we have seen in the Bakken, we are looking at where production is going to be two years, five years or 10 years into the future,” he remarks. “That is the challenge as we try to get new projects put together so we are not undersizing or oversizing projects. We want to have the right size project in place at the right time.”

The latest example of new crude oil rail shipping capacity is the Bakken Oil Express hub, which accepted its first truck deliveries in October, and the first unit train filled with crude departed the facility the first week of November, reports Managing Director Steve Magness. With the first of two phases of construction completed, the hub includes two rail loops, each approximately 8,000 feet long, more than 210,000 barrels of tankage, and a “truck center” with multiple independent bays.

“Interest in the new facility has been very high, and we have been very busy,” Magness says. “We are looking already at making a third expansion by adding additional tanks and tracks.”

Projections vary, but total Williston Basin oil output is expected to double again over the next eight years and could eclipse 1.3 million barrels a day by 2025. While rig counts jump to record levels in the basin and operators await additional pipeline, rail and processing infrastructure to reduce oil and gas transportation bottlenecks, municipalities are transitioning from temporary to permanent housing, and are scrambling to install public infrastructure capable of accommodating a booming population.

“I think the biggest challenge for the region is transitioning from the exploratory phase to the development phase and getting all the necessary infrastructure in place, whether it be from an industry standpoint or for communities needing to catch up and stabilize the workforce by getting more people into homes,” says Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council. “Hopefully, over the next two to three years, we will begin to see that infrastructure catch demand.”

A mild winter by North Dakota standards has helped, allowing companies to speed construction of crude oil and natural gas gathering systems. This year, the industry is spending $3 billion on natural gas infrastructure alone, Ness points out.

Leading Producer

For Oklahoma City-based Continental Resources Inc., the basin’s leading oil producer and largest Bakken leaseholder, with more than 1 million net acres in the play, the lack of gas lines and processing capacity has been one of the few impediments, says President Jeff Hume.

“Fortunately, that is being cured very quickly,” he says. “That field is so large that often we were stepping out 10 or 15 miles to the nearest well. Once production is established, gas trunk lines and compression have to be moved to the locations. We outran the gas plants.”

Although the Bakken is an oil play, it does produce significant amounts of associated gas. In fact, natural gas production in North Dakota has tripled since the Bakken play took off in 2007, and the state had 3,800 wells with some gas sales at the end of 2011.

Continental is moving 160 million cubic feet of gas through two plants that came on line in January, Hume says. Plant additions over the next year and half are expected to allow operators to bring on several hundred million cubic feet a day more, he adds.

In the meantime, there is certainly plenty of drilling left. Continental has identified 3,500 locations on its acreage. If the working rig inventory basinwide averages 200, Williston production could surpass 1 million bbl/d by 2015-16, predicts Hume.

“There is enough inventory for those rigs for a decade or longer, drilling only the Bakken formation,” Hume says. “The rig count is hovering around 215, and likely will plateau over the next few years around 250.”

Continental Resources Inc. is the leading Bakken Shale oil producer and holds the largest acreage position in the play, with more than 1 million net acres. The company has identified 3,500 locations on its acreage and is running 25 rigs in the Bakken/Three Forks play.

Continental is keeping 25 rigs busy. With much of Continental’s position now held by production, its contractors are preparing rig fleets so the company can continue its shift to “eco-pad” drilling. In 2013, Continental plans to have 75 percent of its fleet on pads, Hume says.

“That will cut down on rig moves, require a smaller drilling footprint, and help us gain other efficiencies that will allow our development dollars to go further,” Hume explains. “Pad drilling should save us 10 percent on total drilling costs.”

For Continental and other operators, the high level of drilling translates to an even greater need for crude gathering and transportation infrastructure, he notes. “A lot of pipeline infrastructure is being put in with start dates ranging from mid-2014 to mid-2015,” Hume states. “We should have more of the transportation system lined out within the next three years.”

About 150 of Continental’s 650 employees are based in the Williston, Hume says. While the company has not had to build crew housing, it has donated to local hospitals and emergency agencies.

“I do not see any glaring challenge out there for us,” Hume reports. “The biggest thing is to continue to work. I think the challenge is continuing to do what we have been doing on a larger scale. We stress communication. We spend a lot manpower on training and bringing in a lot of young people who have not worked in the industry before.”

With much of its lease position held by production, Continental Resources continues to shift to “eco-pad” drilling. The company expects to have 75 percent of its contracted fleet on pads by next year, increasing operational efficiencies, minimizing rig moves, creating smaller drilling footprints, and decreasing overall drilling costs.

Continental also will continue to deploy technological solutions to allow it to achieve additional cost savings and efficiency improvements in the Bakken/Three Forks play, including remote well monitoring systems and pump-off controllers, he offers.

“Most pumping units have a pump-off controller. That gives us better efficiency on both a power usage basis and on run time to optimize pump performance. With remote monitoring, we can see early on if a piece of equipment such as a bottom-hole pump starts wearing out, and can schedule maintenance rather than react to a failure and have unscheduled down time,” Hume says.

Market Access

Transportation constraints have cost operators as much as $25 a barrel in discounts to get their crude to market, North Dakota Petroleum Council’s Ness notes, but the construction of up to 12 rail hubs and the quick growth in rail access is giving operators access to multiple markets.

“Rail has given our sweet crude access to nontraditional markets,” Ness says. “That has been helpful, even though our production continues to outpace our ability to export.”

Rail facilities such as the Bakken Oil Express provide producers the flexibility to access a number of destinations served by railroad (Figure 1). “The Bakken Oil Express hub is the first open-access, multiple shipper unit train loading facility operating in North Dakota,” Magness says. “From the facility, crude can be shipped to all major trading hubs.”

Strategically located west of Dickinson, N.D., within the Three Forks play and in proximity to pipelines originating from the heart of the Bakken Shale play, initial rail loading capacity is 100,000 bbl/d with a loading time of less than 12 hours per train, according to Magness. “We are preparing to undertake a second phase of construction to expand loading capacity to 130,000-140,000 bbl/d, or two unit trains a day,” he says.

A subsidiary of Wichita, Ks.-based Lario Logistics, Magness adds that plans are in place that would allow for additional loops, tanks, rail loading racks and pipeline connections to potentially expand facility throughput to more than 200,000 bbl/d. And just as important as getting oil out of the basin, the hub will facilitate getting equipment and supplies moved into the basin. “With 350 acres zoned industrial, the Bakken Oil Express is capable of handling unit trains for shipping oil field service materials,” he notes.

Rail transport accounts for 25 percent of total Williston Basin crude oil transportation export volumes, with the remaining 75 percent shipped by pipeline, Kringstad relates. Despite the current capacity constraints, the transportation outlook is good, he says. “In addition to new rail hubs, six pipeline projects have been announced or are in regulatory review, planning or construction phases,” Kringstad reports. “It is a matter of getting approval and getting the pipelines installed.”

The new Bakken Oil Express rail hub is located west of Dickinson, N.D., and has an initial loading capacity of 100,000 bbl/d. A second phase of construction will expand loading capacity to 130,000-140,000 bbl/d, or two unit trains a day. Eventually, capacity could be increased to more than 200,000 bbl/d.

An example is the new Four Bears Pipeline, which was announced in January, and includes a 12-inch, 77-mile line with 105,000 bbl/d capacity. “Four Bears is expected to eventually reduce truck traffic by 50,000-75,000 miles a day,” says Kringstad.

New Oil Pipeline

In April, Tulsa based ONEOK Partners announced plans to invest $1.5 billion to $1.8 billion in a 1,300-mile, 200,000 bbl/d crude oil pipeline from western North Dakota to the trading hub at Cushing, Ok.

“We are a natural gas pipeline company, and we have been handling gas and natural gas liquids associated with oil production for a number of years and will continue to do so,” says ONEOK spokesman Brad Borror. “But we envision the need for additional crude oil pipeline take-away capacity in the coming years. This is a natural evolution for our business.”

Many of the supply commitments under negotiation are with the same producers ONEOK services in the Williston Basin, according to ONEOK Partners President Terry Spencer. After securing permitting and regulatory compliance, he says the company expects to begin construction in late 2013 or early 2014, with completion planned by early 2015. Based on supply commitments prior to construction, the capacity can be increased as needed.

More than 80 percent of the route parallels the partnership’s existing and planned natural gas liquids pipelines, and will be positioned to also transport crude oil from the Niobrara Shale in Wyoming and Colorado. “As producers continue to aggressively develop crude oil from wells in the Bakken Shale, more crude oil pipeline take-away capacity will be required,” Spencer said while announcing the project. “This proposed pipeline will provide producers with efficient and reliable transportation of their product directly to one of the largest crude oil market hubs in the United States.”

ONEOK previously announced investments totaling $2.8 billion-$3.5 billion through 2014 in “growth projects” in the Williston Basin, including a 500-mile NGL pipeline (the Bakken Pipeline), a 270-mile gas gathering system and related infrastructure in Divide County, N.D., and three 100 MMcf/d natural gas processing facilities (including the Garden Creek plant, which went into service in December).

The North Dakota Legislature has designated $1.2 billion for transportation, housing, public safety, coordinated planning and other infrastructure needs in the state. One of the focal points is road construction projects to accommodate increased traffic, including designated truck routes and bypasses to relieve congestion on community streets. Photo courtesy of the North Dakota Department of Transportation.

According to Continental’s Hume, developments in the Williston are leading a transformation of the nation’s entire crude transportation infrastructure as new lines are announced and others are reversed to connect the basin to major crude trading hubs and refining complexes.

“With enough line reversal, I think the industry will be moving oil to the East Coast in a couple years,” he ventures.

Expanding oil pipelines can work hand-in-hand with rail facilities to optimize efficiencies for operators as they develop their leaseholds and invest in in-field gathering infrastructure, Hume goes on. For example, as Continental expands its pipeline-connected liquids gathering systems, it reduces the need for truck traffic in areas with higher numbers of producing wells. That frees those trucks to be redeployed to newer areas with fewer wells, where gathering infrastructure is not in place, allowing that oil to move to rail connections, he says.

“We hope to plateau a little bit on the number of crude hauling trucks moving from the well to the regional pipeline or regional rail facilities as we build local infrastructure,” Hume says. “That is progressing very fast.”

Economic Impacts

The oil industry is pumping about $2 billion every month into the regional economy in the form or wages, salaries, equipment purchases, and the sale of oil and gas, according to E. Peter Elzi Jr., principal senior economist for THK Associates in Denver, which works for private developers in the region.

Elzi says the booming Williston Basin represents a major inflection point in a modest broader trend line on the nation’s economic growth. “I never thought the road to recovery would lead through Williston,” he offers. “When I describe the boom to clients in Denver, they do not believe me when I say there really are guys making $100,000 a year living in their cars in North Dakota.”

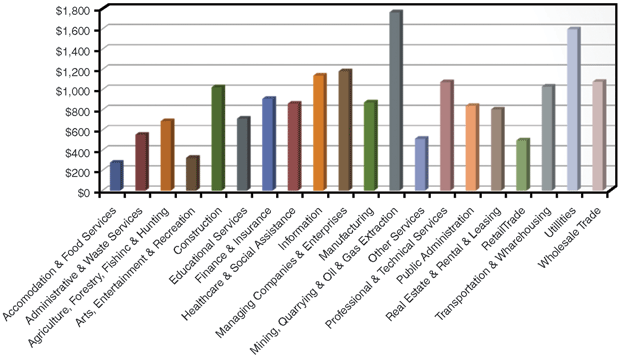

The oil and gas, mining and quarrying sector pays the highest average weekly salaries in North Dakota (Figure 2), and Williams County–with Williston as the county seat–accounts for more than half of North Dakota’s total employment growth in the sector, Elzi says. The county is home to about 25,000 jobs with an average weekly pay approaching $1,400. More than 10,000 jobs have been added in the county since 2009, with average weekly pay growing by two-thirds, he estimates.

By comparison, Ward County, N.D., which includes Minot, has about 35,000 jobs, but weekly pay is just below $800, with the job figures including higher education and other private sector employment that existed prior to the Bakken boom, he notes.

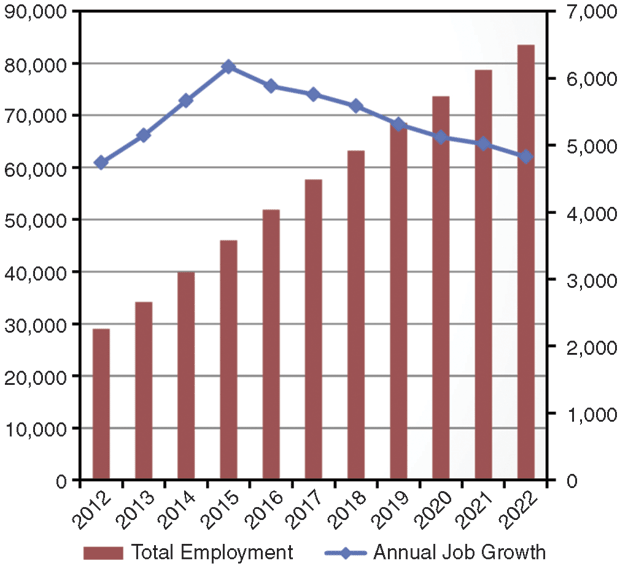

Over the next decades, total employment in Williams County could approach 80,000, although annual job grow will ebb in the future, Elzi says. In Ward County, total jobs are expected to grow to about 60,000.

“Once they are done drilling all the wells in Williams County–and that will probably not happen in my lifetime–and they start drilling more in adjoining counties, those counties will start get a larger share of mining jobs,” he reflects.

Job openings abound in Williston, says Ward Koeser, the city’s mayor for 18 years. There are 3,000-4,000 openings in the immediate area, with just about every business in town displaying help wanted signs in their windows, Koeser points out. Labor shortages are being felt from the school system, which needs 30-40 teachers, to the local hospital, which is short about 60 employees, he says. The local Wal-Mart is looking for 200 additional workers.

“I appreciate all the workers who have come into Williston to serve the oil and gas industry and live in the man camps, but unfortunately, they do not bring others with them to help fill the job vacancies we have all over the city,” Koeser says. “There are no additional teenagers to work at restaurants or spouses who can help in the local clothing or other retail stores.”

Population Shift

An influx of construction and oil field workers has created its own set of challenges, he says, from long lines in stores and traffic congestion on the city’s streets, to housing shortages and stressed municipal utility systems. While the city of Williston has a conservatively estimated population of 20,000, the immediate area is likely home to more than 30,000, counting residents of man camps near the city, says Koeser.

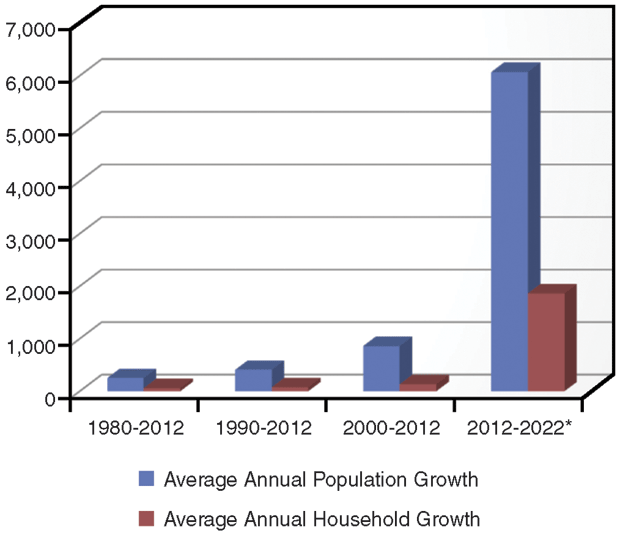

Figure 3A shows projected employment growth in Williams County, while Figure 3B shows historical and projected population and household growth in the county. The 2000 Census put Williston’s population at 12,000, Koeser recalls. Even as late as 2004-05, the city’s population was estimated to be around 13,000, he says.

Elzi estimates as many as 40,000 people could be living in man camps, hotels, motels and RV parks in a four-county area that includes Williams, Ward, McKenzie and Stark counties, N.D.

“God only knows how many people really are living there,” says Elzi, whose firm works for private developers in the region. “Nobody really knows. Ever go to the circus and see a Volkswagen pull up, and 20 clowns get out? That is how I think some of these housing facilities. When I visited the area, I got the cot in what was the ‘family room’ of a 10- x 20-foot trailer. There were five in the trailer that night, and I was thankful I had found a place to sleep.”

Looking forward, Williams County’s population is expected to grow about 6,000 a year for the next decade, Elzi says. While Williston’s population is estimated at 20,000, the entire area is likely home to 60,000 or more when including residents of work camps, hotels, motels, RV parks, etc.

“Williams county could have 60,000 permanent residents over the next 10 years,” Elzi says. “I do not see this thing stopping anytime soon. There are a lot of wells to drill yet.”

Fastest-Growing Area

With the Bakken boom, Williston has become the nation’s fastest-growing “micropolitan” statistical area, a U.S. Census Bureau measure of areas with populations ranging from 10,000 to 49,999.

“It does not surprise us,” Koeser says. “It is intense here. We have had a lot of the national news media here, and they tell me that this is one of the most intense places in the country for growth. The drilling success rate is unbelievable. I believe in the last two years, the state has reported there are no dry holes and it is high-quality sweet oil. If the federal government does not slow things with some kind of regulation, I think it is going to be busy for a long time.”

Williston’s housing shortage remains acute, even with $350 million spent last year on residential and commercial projects, Koeser reports, in addition to $6 million the city contributed to temporarily expand the sewer system so more projects could come on line.

By the end of August, another 1,000 or so housing units–from apartment complexes to new single-family homes–are expected to be available, with the city needing two or three times that many new units this year alone, he says. “We need 2,000-3,000 each year for the next three to four years to get caught up,” Koeser remarks.

If 75-80 percent of existing residents were to eventually transition from temporary living quarters to permanent housing, Williams, Ward, McKenzie and Stark counties would need an additional 13,000-14,000 housing units to have a normal housing stock, Elzi says.

Despite the housing constraints, businesses keep moving in, further fueling housing demand. As many as 400 oil field service companies have set up shop in the area, Koeser says, ranging from one-man operations to the major companies. The 10 largest service companies in the world all have local offices in Williston, he adds.

“It seems weekly that a new oil field service or supply store opens,” says Koeser, owner of Kotana Communications. He says he relocated to Williston from Montana in 1978 to launch a business selling and servicing communications equipment to the oil and gas industry. “Our city is located in the middle of oil production for the basin. Service companies tend to look here first for new locations, although they do not all move to Williston because of the shortage of commercial space to buy or rent.”

Williston, in conjunction with the state of North Dakota, is sharing the risk of growth after a boom-and-bust cycle in the 1980s left the city with $28 million in debt that had to be paid. “The Bakken play is different from the oil boom of the 1980s. This time we have been getting support actively from the state, and anticipate receiving more,” Koeser says. “We also have asked for more involvement from developers. We require them to put in infrastructure with their projects. The city does not want to get stuck with a lot of debt.”

Rerouting Truck Traffic

In January, representatives of nine North Dakota agencies traveled to 14 cities to learn more from local leaders on infrastructure needs, how to better carry out coordinated responses, and to update leaders and state officials on progress from $1.2 billion set aside by the legislature during the current biennium for transportation, housing, public safety and coordinated planning, says North Dakota Commerce Commissioner Al Anderson.

As of mid-April, $800 million of the state funding had been distributed. State funding comes amid changing local sentiments in light of the boom’s impact on communities, he says. “Over the past several decades, North Dakota had been depopulating, so the last thing local leaders wanted was a highway bypass around their city,” Anderson says. “They wanted traffic coming right through downtown.”

But long lines of oil field truck traffic have changed that, he says. Now, local leaders want designated truck routes to relieve traffic congestion, especially in Williston, New Town, and Watford City. “The first step for local leaders is to gain local support for projects, then it is easier to get those reliever routes in place,” he says.

Typically, the process of building a truck bypass would take three to five years to gain regulatory approval, secure rights-of-way, compile the required environmental impact statements and build the roads, Anderson says. But a temporary truck route on the west side of Williston is expected to open in summer after bids in April.

“It will not be perfect, but diverting some of that traffic outside the city is one of the biggest concerns those communities have from a safety and road maintenance perspective,” he says.

Other projects will expand regional highways to four lanes and add passing lanes.

“It is truly incredible,” Anderson says. “Cities are growing that in the past were declining, and it presents different challenges, but they are challenges we would much prefer to address than closing schools and trying to encourage main street development.”

A large truck stop, which will include additional truck parking, is going in on the north side of Williston, which should reduce the need for trucks to park all over the city, Koeser says.

“I think down the road a couple years, we are going to be a better town than when we started this whole thing,” he says.

Real Estate Development

Builders continue to work with available labor and coordinate construction logistics to get more housing and commercial property open, says Doug Walker, president of Nakota Property Management. The company is building two extended-stay Value Place™ hotels, scheduled to open mid-July and 68 walk-up and 19 garage storage units in Williston, he reports. Walker says Nakota also plans to start construction on two additional Value Place hotels in the region this summer, and plans are being completed for a 400-unit apartment complex to be located in Williston.

But rounding up crews and finding adequate housing for construction workers continues to be a challenge, Walker says. Nakota has installed some temporary worker housing in Value Place rooms that already are completed.

“The plumbers will come in and leave, then the framers will come in and leave, and then the sheetrockers, then the painters, etc.” he says. “We use the same housing for multiple trades. They come in, do their part and then move on to the next site.”

But not everyone who shows up stays to complete the work, he adds. Despite the mild winter, one out-of-state crew left early when it got colder. “Keeping up worker morale is a big issue,” Walker says. “Crews are anxious to get there and work, but after they get there for a while, they want an extended break to get home. To help, we have cookouts for the crews, and we have put satellite-connected televisions in all the units we have brought in for housing.”

With local labor taken, Nakota and other developers work together to screen crews and provide references on the quality of their work, he says. “These guys are coming from all over the nation, so you cannot drive by their last project to find out what kind of work they did. You have to vet crews,” Walker says. “They do not all come with the level of expertise they might say they have. We started with a couple crews that did not do the quality of work we required, so we had to let them go and brought in new crews. That is a tough way to do construction. By working with other developers, we can look at their sites and they can look at ours to see how crews are performing.”

Local construction material supply shops are small and have limited selection, forcing contractors to buy in bulk and ship in material as needed to avoid exposing material to the weather because of a lack of covered storage capacity, he says.

Transportation costs for material are also high because material hauling flatbeds have to return to base empty because of the lack of return-haul opportunities in the region, Walker explains. “It’s hard to load oil onto a flatbed,” he quips.

Development of commercial space is picking up, he adds, although much of the commercial development includes oil and gas companies building their own multiple-use facilities, which typically include a combination of warehouse and office space.

Financing for projects is becoming more available for some projects, but remains tight for speculative commercial developments, Walker observes. Explaining development opportunities in North Dakota to potential financiers brings its own set of challenges, he adds.

“You call people and say you have a development project in North Dakota,” he reflects. “If they are still on the line after that, you tell them it is in Williston. Then they ask where in the world Williston is. As much press as Williston has gotten because of the boom, there are still people who are unfamiliar with it.”

The growth has been a boon to municipal tax revenues, Elzi points out, with Williston’s tax collections now higher than collections in Fargo, the state’s largest city. Williston is expected to see retail sales of $800 million in 2012, he adds.

The four-county area has 4.8 million square feet of commercial space, with an additional 4.2 million expected to be added over the next decade, he says.

“The biggest challenge commercially is finding labor,” he says. “While you might be able to fill jobs paying $80,000-$120,000 a year, getting somebody to come to town and work for $20 an hour and find housing are bigger issues.”

Capital Formation

Acreage throughout the play continues to move into the hands of well capitalized larger independent companies, notes Michael Nepveux, managing director of Wells Fargo Energy Capital in Denver, which specializes in serving operators with deal sizes of $100 million or less.

“But there are still many small producers who have nonoperated minority working interests in drilling service units operated by the larger companies,” he adds. “And larger, nonoperating interest holders also continue to assume greater positions as smaller operators choose to sell their acreage.”

With well costs running $10 million-$12 million, small companies holding several thousand acres can find it difficult to cover the cost of authorizations for expenditure issued by a large operator, Nepveux says, adding that operators typically earn three times the amount of an AFE a smaller interest holder pays.

“A lot of them see $20 million-$30 million in bills coming their way in the next 12 months, and they want to pay those AFEs and participate in those wells,” says Nepveux. “If they do not, that constitutes a nonconsent and the operator essentially gets most of the economics from their piece.”

Smaller companies with enough production and wells can borrow at low rates from commercial banks that shy away from companies lacking adequate size to address concerns about risk, he adds. For those operators, mezzanine financing remains available in the Williston Basin, Nepveux says.

“If we like the people, their assets, and the well operator, we will pay 100 percent of the cost of their portion of the AFE, and in exchange, we get an equity interest in their acreage,” he explains.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.