Natural Gas Outlook

U.S. Natural Gas Supply Expanding To Surplus Levels, Demand Growth Will Follow

By E. Russell “Rusty” Braziel

HOUSTON–For most of the 150 years of U.S. oil and gas production, natural gas has played second fiddle to oil. That appeared to change in the mid-2000s, when natural gas became the star of the shale revolution, and eight of every 10 rigs were chasing gas targets.

But natural gas turned out to be a shooting star. Thanks to the industry’s incredible success in leveraging game-changing technology to commercialize ultralow-permeability reservoirs, the market was looking at a supply glut by 2010, with prices below producer break-even values in many dry gas shale plays.

Everyone knows what happened next. The shale revolution quickly transitioned to crude oil production, and eight of every 10 rigs suddenly were drilling liquids. What many in the industry did not realize initially, however, is that tight oil and natural gas liquids plays would yield substantial associated gas volumes. With ongoing, dramatic per-well productivity increases in shale plays, and associated dry gas flowing from liquids resource plays, the beat just keeps going with respect to growth in oil, NGL and natural gas supplies in the United States.

Today’s market conditions certainly are not what had once been envisioned for clean, affordable and reliable natural gas. But producers can rest assured that vision of a vibrant, growing and stable market will become a reality; it just will take more time to materialize. There is no doubt that significant demand growth is coming, driven by increased consumption in industrial plants and natural gas-fired power generation, as well as exports, including growing pipeline exports to Mexico and overseas shipments of liquefied natural gas.

Just over the horizon, the natural gas star is poised to again shine brightly. But in the interim, what happens to the supply/demand equation? This is a critically important question for natural gas producers, midstream companies and end-users alike.

Natural gas production in the lower-48 states has increased from less than 50 billion cubic feet a day in 2005 to about 70 Bcf/d today. This is an increase of 40 percent over nine years, or a compound annual growth rate of about 4 percent. There is no indication that this rate of increase is slowing. In fact, with continuing improvements in drilling efficiency and effectiveness, natural gas production is forecast to reach almost 90 Bcf/d by 2020, representing another 29 percent increase over 2014 output.

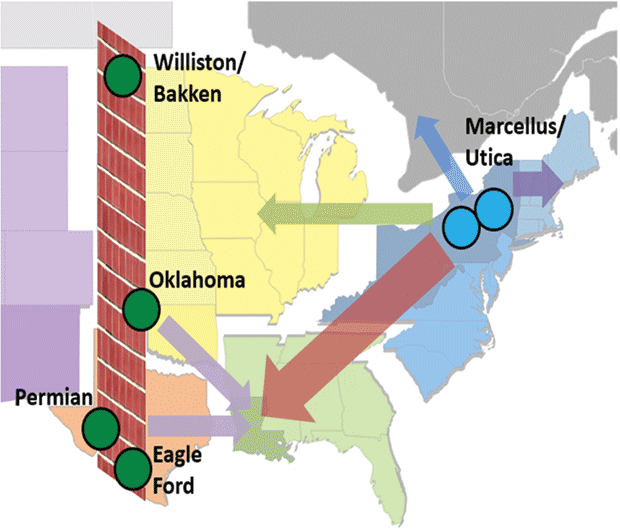

Most of this production growth is concentrated in a few extremely prolific producing regions. Four of these are in a fairway that runs from the Texas Gulf Coast to North Dakota through the middle section of the country, and encompasses the Eagle Ford, the Permian Basin, the Granite Wash, the South Central Oklahoma Oil Play and other basins in Oklahoma, and the Williston Basin. The other major producing region is the Marcellus and Utica shales in the Northeast. Almost all the natural gas supply growth is coming from these regions.

Production in the Northeast is particularly abundant, with volumes increasing from 2 Bcf/d in 2008 to more than 18 Bcf/d in 2014. That astronomical growth rate is expected to continue, reaching 30 Bcf/d by 2020.

This much gas far exceeds the infrastructure available to move those supplies to market, and in fact, exceeds the ability for markets in the Northeast to use all the gas. Even though the Northeast market is one of the largest in the country, regional production is on track to exceed regional demand on a net basis next year. After that, a burgeoning supply surplus can be expected to develop.

Northeast Pipeline Capacity

The need for new pipeline capacity to move this surplus out of the Northeast has been recognized by the midstream sector, and more than 60 pipeline projects have been announced to facilitate transporting regional supplies. Some of these projects are new “greenfield” developments, but many are reversals of existing pipelines that historically transported gas into the area. Such pipelines are being modified to take gas out of the Northeast to relieve take-away constraints that have developed as production has increased. Those take-away constraints resulted in Northeast natural gas prices averaging $2.00-$2.50 an MMBtu below the Henry Hub price during most of 2014.

Of the announced pipeline projects, 41 actually increase take-away capacity while the remaining projects simply shuffle gas supplies within the region. Approximately 28 Bcf/d of take-away capacity is being added by these projects, with flows moving to New England, Eastern Canada, the Midwest, and especially, the U.S. Gulf Coast. About 16 Bcf/d (nearly 60 percent) of that capacity targets the Gulf Coast as the destination market. In an ironic shift, the region that historically provided most of the Northeast’s natural gas supply will soon be the demand region receiving most of the Northeast’s gas surplus.

As Northeast gas rushes out of the region, the central question becomes, “Where is all that gas going to go?”

Basically, it is a two-part answer. The first, and most obvious, destination market for Northeast surpluses is incremental demand in the form of new gas-fired power generation, industrial demand, and LNG exports. Over time, these demand sources can absorb a significant portion of the surplus. Since much of that demand growth is in areas outside the Northeast, the pipeline capacity being added is not only necessary to relieve the region’s take-away constraints, but it is equally needed to move gas supplies to growing markets (most of which are in the southeastern portion of the country).

However, it will take several years for that new demand to develop. In the meantime, and the second part of the answer, is that surplus Northeast gas will take market share from other North American producing regions. Over the next few years, these supplies will displace gas that previously moved into the Northeast from Canada, the Rocky Mountains, the Mid-Continent, and the Gulf Coast. As new pipeline expansions provide routes to physically move gas into those markets, Northeast gas will be able to capture market share from what in the past have been secure markets for local producers.

Hitting A Wall

But there is a problem in the competition for market share: The Northeast is not the only supply region experiencing growth. Producing regions in the middle part of the nation–the Eagle Ford, Permian, Oklahoma and the greater Rockies (Williston/Niobrara)–are growing also, primarily from gas associated with crude oil production and high-Btu wet gas that contains large quantities of natural gas liquids.

Figure 1 suggests the implications. Most of the production growth from the Northeast will move west, but those flows will encounter significant market competition–in effect, a wall of increasing supply coming from those four producing regions. All of that gas supply is driven by the economics of oil and NGLs, so much so that natural gas frequently is relegated to byproduct status. In other words, natural gas is produced because it comes along with the oil, not because of the value of the gas itself.

But that does not mean natural gas production is not increasing rapidly in those liquids plays. In fact, pipeline capacity and markets’ ability to absorb gas from these regions are nearing maximum, with limited outlets to the West or the Midwest. That leaves only one outlet for those supplies: the Gulf Coast. The implication is that Northeast supplies bearing down on the Gulf Coast will run directly into supplies from Western basins, with the collision of gas flows occurring primarily in the Southeast and centered in Louisiana.

This is not the first time a significant ramp-up in natural gas supply that started in one region has collided with production from another area to result in significant market disruption. About 10 years ago, a similar sequence of events roiled U.S. natural gas markets, starting in the Rockies and culminating in a radical resetting of price expectations at the Henry Hub. At that time, the chain of events began to play out when supply growth in the Rockies exceeded the infrastructure’s ability to get that supply out of the region. The lack of take-away capacity resulted in a regional price collapse.

However, the rest of the national market, represented by Henry Hub prices, was protected from the impacts by the same constraints that made the local impact so severe. In essence, the oversupply monster was fenced in.

Eventually, the capacity constraints were relieved, primarily by the completion of the Rockies Express Pipeline from Wyoming to interconnections in Ohio. The oversupply monster got out. The local market saw immediate relief as its prices approached national levels, but the now-free supply surge hit national markets, causing prices to begin falling.

At almost the same time the Rockies supply surge reached the market, it was joined by simultaneous and competing supply growth from new shale plays (namely the Haynesville, Fayetteville and Barnett) coming into Louisiana on new pipeline capacity from Texas and Oklahoma. All this supply eventually converged on the Henry Hub, and prices fell low enough to discourage drilling in both the Rockies and the new shale plays.

That threshold price turned out to be an economic break-even price of about $4.00 an MMBtu. Not coincidentally, the national price at the Henry Hub declined to about $4.00/MMBtu and has gravitated around that level ever since.

Timing Problem

Today’s market conditions are somewhat similar to the market share competition a decade ago between Rockies gas and gas from new shale plays. But this time, it is Northeast gas versus gas from Western shale basins. With supply pouring into the Southeast market from the east and west, significant increases in demand will be necessary to balance the market.

Unfortunately, the largest demand sector–residential and commercial–has been essentially flat for years because of the combined effect of efficiency and conservation gains. That is unlikely to change. Therefore, any demand increase will need to come from some combination of the industrial sector, the power sector, and the export market (both in the form of LNG and increased pipeline exports to Mexico).

Demand from the industrial and power sectors certainly has responded in the past. Between 2005 and 2014, natural gas industrial demand was up 2.9 Bcf/d (16 percent) while demand for power generation was up 6.0 Bcf/d (37 percent). Although those increases are significant, they obviously are well below the 40 percent production growth during the same time frame.

The market balanced by backing out imports from Canada as well as LNG shipments from overseas suppliers. A combination of demand and supply adjustments was required to balance the market. It is likely that the same kind of adjustments will be needed over the next few years.

Consider a very healthy 2014-20 demand scenario in which gas-fired power generation grows by another 8 Bcf/d (or 36 percent), industrial demand increases 4 Bcf/d (20 percent), and combined industrial and residential/commercial demand is flat. While such a projection of 12 Bcf/d in domestic demand growth is aggressive, it still falls well short of the 20 Bcf/d supply growth outlook over the next five years.

Of course, the balancing item is expected to be exports, both to Mexico and overseas LNG. Mexico’s demand for U.S. gas is expected to increase, which will take up some of the surplus. But the lion’s share of the surplus will be exported as LNG.

More than 10 Bcf/d of LNG export projects have advanced sufficiently through the regulatory process to be expected to move forward, with at least another 2.2 Bcf/d being likely. These projects ultimately will total about 13 Bcf/d of capacity, with 80 percent of that along the Gulf Coast. Almost half, or 6.5 Bcf/d of capacity, is planned for the Louisiana Gulf Coast. Combined with 1.0 Bcf/d-2.0 Bcf/d increased exports to Mexico, that would be more than enough export capacity to balance the market.

The problem is timing. Sabine Pass, the first LNG export facility expected to come on line, is not expected to be operational until late 2015. The rest are not planned until 2018-20, at best. In the ensuing years of 2015 through early 2018, natural gas production will be growing dramatically while LNG export capacity is under construction. The timing problem is exacerbated further by the demand growth trajectories expected for industrial and power demand.

Even assuming demand grows by 12 Bcf/d by 2020, that growth will be incremental at about 2.0 Bcf/d per year. Consequently, even if enough demand eventually materializes to absorb all the projected growth in production, there still could be a supply overhang of more than 5.0 Bcf/d beginning in 2015 and continuing until demand catches up in 2018. The bottom line is that if all that gas gets produced, there is nowhere for it to go until new demand in the form of industrial plants, natural gas-fired generation, and export capacity becomes operational, and that is at least four years out.

As was the case with gas-on-gas competition between the Rockies and early dry gas shale plays, the implication is that the supply side must help balance the supply/demand equation. But backing out imports will be extremely difficult. LNG imports are at zero, while imports from Canada have nowhere else to go. That suggests that in the medium term, the only way the glut of supply can be relieved is for producers to cut back drilling in response to gas prices declining below their break-even price levels.

Breaking Even

Consequently, mirroring the market share competition between the Rockies and early shale plays, gas-on-gas competition between the Northeast and Western shale plays likewise will be concentrated in the Southeast, with much of the surplus gas flowing into Louisiana. But there is one significant difference today: break-even price levels.

The break-even price for most dry gas in 2009-10 was about $4.00 an MMBtu. When oversupply required producer cutbacks, the price fell to a level at or slightly below that price, discouraging drilling activity in marginal plays (which turned out to be primarily higher-cost, dry gas-producing regions such as the Haynesville and Barnett).

Break-even prices are much lower now. Marcellus dry production remains slightly above zero internal rate of return at a price of only $2.00/MMBtu. Wet Marcellus remains above 40 percent IRR at $2.00/MMBtu, since producers are making most of their money from NGLs. Even more dramatic are the core areas of the Bakken, Eagle Ford, Niobrara and Permian. With much of the production value coming from crude oil and NGLs, these plays can remain profitable at a natural gas price of essentially zero. This is the case even at crude prices in the range of $75 a barrel.

Accordingly, while the supply/demand balance scenario is similar to that of the Rockies/dry shale gas play conflict, the implied floor to which natural gas prices could fall is much lower. If the average break-even price was $4.00 an MMBtu in the 2009-10 gas-on-gas competition, it is closer to $2.50/MMBtu today. As increasing natural gas production volumes descend on the Louisiana area over the next few years, there is little besides curtailing gas drilling that can balance the market.

As new pipeline projects relieve take-away constraints on Northeast gas over the next five years, surplus volumes will escape their constraints and relieve the basis differential penalties being experienced by Marcellus/Utica producers. The negative price differentials in the Northeast will dissipate. But the important question is how this will impact the price outlook for the overall market, represented by the benchmark natural gas price at Henry Hub.

Henry Hub is at the epicenter of gas inflows from the Marcellus/Utica and oil/wet gas shale plays. Based on the demand scenario presented in this article, gas will have to be priced low enough to discourage drilling activity, presumably at a level below break-even prices in high-growth basins.

Of course, it is the natural gas market, and weather could resolve most of the oversupply issues. But the sobering fact is that if polar vortex weather had not pulled down inventories so hard during the winter of 2013-14, the supply overhang likely would have disrupted the market last summer. Such frigid weather this winter could buy the market another reprieve. But whether this year or next, a supply glut appears slated to return in the not-too-distant future.

By the turn of the decade, this oversupply situation should be behind the market as new gas-fired generation, industrial capacity and exports balance supply and demand. In the meantime, however, it will be a tough market for producers, where efficiency, effectiveness and low-cost operations will be critical to success.

E. RUSSELL “RUSTY” BRAZIEL is president of RBN Energy LLC in Houston. He formerly served as vice president of sales and marketing at BENTEK Energy, a Platts company. Before Platts acquired the company in 2010, Braziel was co-owner and managing director of BENTEK Energy LLC. During his three-decade career, he has worked as a programmer, analyst, planner and energy trader. He was vice president of energy marketing and trading for Texaco (now Chevron), and vice president of business development for Williams. Braziel also founded and served as president and chief executive officer of Altra Energy Technologies, a developer of energy transaction management software and electronic trading systems. He is a director on the North American Energy Standards Board and a director of Black Elk Refining in Wyoming. Braziel holds a B.B.A. and an M.B.A. in business and finance from Stephen F. Austin University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.