LNG Emerging As Fuel Of Choice For Vessels, Ferries

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

Harvey Gulf International Marine announced plans in mid-June to build and operate the first liquefied natural gas marine fueling facility in the United States at its vessel facility in Port Fourchon, La. The facility is expected to begin service in February 2014, and will support a fleet of six offshore supply vessels that Harvey Gulf has on order. Once it takes delivery of those new ships, Harvey Gulf will become the largest owner and operator of LNG-powered offshore vessels in the world, says Shane Guidry, chief executive officer.

“To date, Harvey Gulf is the only company in North America that has committed $400 million to build, own and operate LNG-powered offshore support vessels as well as two LNG fueling docks,” Guidry stated while announcing the fueling facility.

The facility will consist of two docks, each with 270,000 gallons of LNG storage and the capacity to transfer 500 gallons of fuel a minute, as well as the capability to fuel land vehicles that operate on LNG.

The advanced Wärtsilä LNG-fueled engines powering the M/S Viking Grace make it the “greenest and quietest ferry in the world,” according to Viking Cruise Lines. The 218-meter long, 57,600-ton vessel completed its maiden voyage in January. It has a cruising speed of 22 knots and is designed to accommodate up to 2,800 passengers. Image courtesy of Viking Cruise Lines.

The Harvey Gulf fleet support facility announcement was the latest in a flurry of similar plans that have accelerated LNG-fueled ships from a novelty to a burgeoning market. Just a few weeks before the Harvey Gulf announcement, Interlake Steamship Co., a major bulk carrier on the Great Lakes, struck a deal with Shell Petroleum to supply LNG so Interlake could convert its vessels.

Those bulk carriers are expected to be the first LNG-powered ships on the Great Lakes and among the first in the United States. With a goal of converting the first vessel by the spring of 2015, Interlake reports it already is working through engineering and design, seeking regulatory approval, and securing financing. Under the agreement, Shell will be Interlake’s exclusive supplier of LNG.

Shell also announced plans in April to invest in a liquefaction unit at its Sarnia Manufacturing Centre in Ontario, Canada. Once operational, that project will supply LNG fuel throughout the Great Lakes, the bordering U.S. states, Canadian provinces, and the St. Lawrence Seaway.

In addition to the Sarnia plant, Shell reports that it plans to install two smaller-scale liquefaction plants for making transportation fuel: one at Geismar, La., which is being designed with marine use in mind, and another in Alberta, which the company says likely will be used for on-road and high-horsepower applications.

And late last year, containership operator Tote Inc. committed to constructing two state-of-the-art, dual-fuel container ships for the Puerto Rico trade, with options for three more vessels for additional domestic service. The vessels will be capable of carrying 3,100 20-foot-equivalent unit containers, and are expected to be the largest ships of any kind powered primarily by LNG. Both ships will be powered by LNG engines, but also will be capable of operating on low-sulfur marine diesel.

Beyond those developments, the two largest ferry operators in North America–Washington State Ferries and British Columbia Ferries–have unveiled plans for both converting existing vessels to LNG as well as dedicated new builds. Their smaller eastern counterparts are moving even more quickly: the Province of Quebec will take delivery of an LNG ferry by the end of next year, and one of the Staten Island ferries in New York also is slated to be converted to LNG next year.

Time Has Come For LNG

“There are about 30 LNG-powered vessels in service worldwide today,” estimates Marcel LaRoche, marine manager for western Canada for Lloyd’s Register. “There are another 30 or so in design or construction. That is not counting the almost 400 LNG carriers, many of which are dual fuel, so they can decide on the fly whether to burn their boil-off or regasify it, based on the relative prices of LNG and other fuels.”

LaRoche says it is clear that LNG as a marine fuel is an idea whose time has come, both in terms of reduced emissions (nitrogen oxide, sulfur oxide and particulate matter) as compared with heavy bunker oil and even low-sulfur marine diesel, and in terms of operating costs. He notes that the leading expenses for ship operators are fuel and personnel.

LaRoche explains that all the seaboards off both the East and West coasts of the United States and Canada, as well as most of northern Europe, are emission control areas (ECAs) as adopted in amendments to Annex VI of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships.

Annex VI imposes progressively stricter emission limits on the global shipping industry over the next decade, with the most stringent requirements within ECAs that encompass a 200-nautical mile band around most of North America and the Hawaiian Islands, and 40-50 nautical miles around Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Mediterranean Sea and Japanese coastal waters are possible future control areas, according to LaRoche.

“We and others have recognized LNG as a fuel source for some time, and now there are operators stepping to the plate with hard cash,” says LaRoche. “The ferries and offshore vessels are obvious markets because they can return to the same terminal for fuel. But it is when you start to see the investment in bunkering operations such Shell’s bunkering strategy that you know LNG-powered ships are not only real, but are an expanding market.”

Other indicators, LaRoche advises, are the development of commercial bunkering barge designs, and an increase in dialogue around applying LNG as a fuel for U.S. inland service. “The buzz is all around the ‘brown water’ fleet,” he states. “That is really where you start to see the math work, and that is the kind of thing that gets the natural gas suppliers excited. Inland marine is the golden goose for LNG-powered vessels in North America, and is a market that is very active already in the Netherlands, where Lloyd’s Register has supported the safe design, building and operation of LNG-fueled tankers and a range of inland waterway ships. The same market is very active on China’s main rivers.”

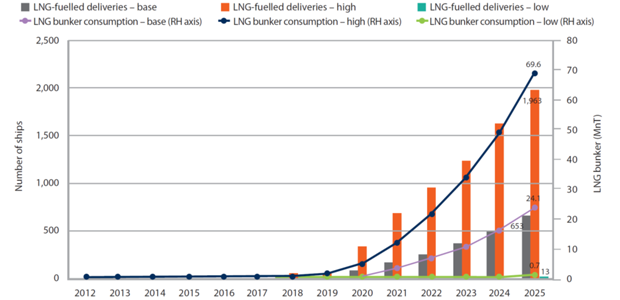

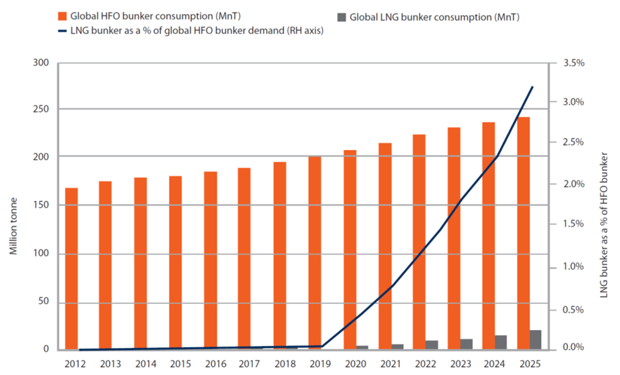

What is much harder to quantify is even a rough estimate of how much natural gas the marine market could consume. Figure 1 shows Lloyd’s Register’s base-, high- and low-case forecasts for new-build LNG-fueled vessels and LNG bunker demand growth for deep-sea trades through 2025. The base case forecasts 653 new-build LNG vessels and 24 million tons of annual LNG bunker demand, while the high case projects 1,963 LNG new-builds and 66 million tons of annual LNG bunker demand by 2025. Figure 2 shows Lloyd’s Register’s base case for projected global LNG versus heavy fuel oil (HFO) bunker consumption for all deep sea ship types through 2025.

FIGURE 1

Cumulative Global LNG-Fueled New-Builds and LNG Bunker Consumption (Base, High and Low Cases)

Source: Lloyd’s Register

FIGURE 2

Base Case of LNG versus HFO Global Bunker Consumption (All Deep Sea Ship Types)

Source: Lloyd’s Register

LNG has about 60 percent of the Btu value of an equivalent volume of marine diesel, so it takes 1.7 gallons of LNG to produce the same power as one gallon of diesel. However, the lower cost of LNG combined with lower emissions gives LNG an advantage in operating costs. Various studies have put that advantage at anywhere from 15 to 30 percent or more, depending on the price differential between the two fuels.

Lloyd’s Register categorizes New York, Houston, San Francisco and Los Angeles as tier 1 ports for developing LNG fuel, meaning they fulfill at least two of the primary considerations:

- They are known bunkering ports.

- They are known to be looking at their potential as LNG bunkering sites.

- The supply of LNG is within a 50 mile radius.

- The port is along a main deep-sea trade route.

Tested And Proven

LNG offers the best economics to shipowners and the best environmental benefits to the public, according to a report by ship classification society Det Norsk Veritas (DNV). “Over the past few years, the technical obstacles to implementing this solution have been eliminated, and LNG as a fuel has been tested and proven already,” the report states. “Furthermore, LNG operations are proven safe with a track record from LNG carriers through the past 50 years without any major safety incident recorded.”

In the report, titled Greener Shipping in North America, DNV points out that the first ship with LNG propulsion (the passenger ferry Glutra) was launched in 2001 as a result of a requirement from the Norwegian government. Next came an offshore supply vessel that was designed for LNG propulsion because the operator could balance the emission savings against increased emissions from an onshore plant. Since then, several more ferries and supply vessels have been built, along with three patrol vessels for the Norwegian Coast Guard.

The DNV report notes only two minor technical challenges, which engine makers are in the process of resolving. “The manufacturers focus on eliminating the so-called methane slip, where a small trace of gas fuel passes uncombusted through the engine and is emitted with the exhaust gas. This is expected to be solved in the near future,” the report states. “Another focus area is developing noncylindrical tanks suitable for fitting in hulls with less available space. All technical issues have been solved. The industry is now working on optimizing design.”

Turning to terminals, DNV observes that until two or three years ago, the North American natural gas market was heavily dependent on LNG imports, and all projections indicated this reliance would only increase. Based on those projections, a number of LNG import terminals were proposed and constructed along North American coastlines. With new U.S. natural gas supplies from shale plays, those LNG import terminals are significantly underutilized. “Although they were not set up to re-export LNG in smaller volumes for domestic use, this is an opportunity the import terminal operators should realize,” the report notes.

FIGURE 3

Existing (Blue) and Approved (Green) LNG Fueling Terminals

Source: DNV North America Maritime

Figure 3 shows a map of existing (blue dots) and planned/approved (green boxes) U.S. LNG fueling terminals. The facilities approved for construction would expand the number of LNG terminals from 12 to 31 over the next few years, according to DNV.

In its conclusion, DNV writes, “It cannot be expected that commercial ships in domestic trades will bunker directly from the import terminal, so a supply chain of smaller LNG carriers, barges, bunker stations, and storage tanks must be developed. And it should be developed with the customer in mind (i.e., the LNG must come to where the ships need it, not the other way around).”

Infrastructure Development

Beyond the cost of converting ships, the single biggest impediment to the near-term development of LNG as a significant maritime fuel is the need to build additional LNG production infrastructure to support marine vessel conversions, according to a report by the American Clean Skies Foundation (ACSF). That infrastructure development “could double the price of delivered LNG relative to the commodity price of the natural gas being liquefied, thus eroding annual fuel cost savings after vessel conversion to LNG,” the report states.

“In addition, the LNG delivered price is highly dependent on both the size and utilization rate of the LNG plant,” according to ACSF. “[Environmental consultants] MJ Bradley & Assoc. estimates the practical minimum for cost-effective LNG production would be a plant sized for 100,000 gallons of LNG a day, operated at an average utilization of at least 80 percent. Such a plant, if dedicated to the marine market, would need a client base of approximately seven Great Lakes bulk carriers, 24 ferries or 38 tugs, to be economically viable.”

ACSF reasons that the economics of any particular marine LNG project would be improved significantly, if the project could take advantage of existing LNG import or production capacity within a reasonable distance of the vessel home port. Looking at all four U.S. coasts, the foundation notes that there are several LNG liquefaction/storage facilities near the Great Lakes that could be used to support LNG conversions. As a potential market, ACSF counts the U.S. Coast Guard vessels for 55 Great Lakes bulk carriers, of the type being converted by Interlake. There are also 243 tugs and 83 ferries operating in and around the Great Lakes, although not all of these vessels would be good candidates for LNG conversion.

There also are several LNG liquefaction/storage facilities close to the Central Atlantic Coast, says ACSF. Those could support converting 590 tugs and 246 ferries operating in the New York/New Jersey region. On the Northwest Pacific Coast, there is an LNG liquefaction/storage facility that could support converting ferries, particularly the Washington State Ferry system and international ferries operating between the United States and British Columbia–a total of 97 vessels–as well as 11 cruise vessels operating between Seattle and Alaska.

Finally, the report says there are several LNG import terminals on the Gulf Coast that could be used to support converting 949 tugs and 63 ferries operating in the lower Mississippi River, and in Louisiana and Texas ports serving Gulf Coast marine traffic.

ACSF says it is “optimistic about the prospects for increased use of natural gas as a marine fuel,” but warns LNG conversion will not be an obvious choice for all vessels. Despite very favorable natural gas prices relative to marine distillate and residual fuel, annual fuel cost savings after converting to LNG may not be large enough to provide a reasonable payback for the cost of converting many vessels, the report concludes.

“Successful projects will require both a motivated vessel owner and a motivated LNG supplier. Given significant first-mover disadvantages, initial projects also may require government intervention to offset some of the cost of converting vessels and/or developing LNG infrastructure in the context of promoting greater use of domestic fuels for transportation,” ACSF opines. “After one or more vessel conversions within a given geographic area, further vessel conversions will become easier to implement.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.