Artificial Lift Engineers Leverage Digital Smarts And Rugged New Hardware

By Danny Boyd

Selecting the right artificial lift system for each stage of a well’s life has long been a key element of optimizing its performance and obtaining consistent financial returns. Today, production engineers have an even bigger toolbox thanks to incremental improvements to familiar concepts and powerful new ideas that are extending many artificial lift techniques’ operating windows and strengthening their resilience to harsh environments, gas slugs and power disruptions.

But no matter how flexible and robust artificial lift systems become, maximizing their economics requires periodic fine-tuning that once would have required hours of tedious analysis. As remote management of artificial lift systems improves and well operations become more autonomous, it is freeing engineers from routine adjustments so they can focus on solving novel problems.

As platforms for managing artificial lift systems evolve, they are getting better at highlighting critical information and automating complex optimizations. According to ChampionX, such automation soon will consider external factors, such as commodity prices and electricity costs.

“We have been on the intelligent automation journey for a while, but there remains a lot of untapped potential,” reflects Derek Meier, product line manager for production optimization software at ChampionX. “There is a lot more we are able to do and will be able to do in the near future around autonomous control and intelligent automation to help operations staff make better decisions and squeeze as much as possible from existing wells.”

With that goal in mind, Meier says the company is developing AI-assisted tools that can guide artificial lift systems based not only on technical factors, but also on macro ones such as the price of oil and real-time energy costs. He says this step forward will help operators meet goals for well production and ultimately return on investment.

The challenge for remote management software is the same as always: to convert massive volumes of data into useful information, Meier says. With the earliest systems, he recounts, data on well behavior and output had to be combined from four or five sources before analysis. Modern software turns real-time data from SCADA systems, such as production, pressure and pump status, into useful information for day-to-day operations. For example, the company’s platform for rod lift systems places key metrics on control room dashboards to allow staff to make important decisions and tweak operations in seconds.

Today, Meier says the system can leverage historical information to create accurate facsimiles of data that is not available immediately. “We are able to benchmark data that is not available in real time back into a broader scheme of automated datasets for validation,” he explains. “And this bigger picture, with the analysis connecting it all together, is what delivers results that would be impossible to get with traditional SCADA or regular data acquisition systems that are missing the subject matter expertise for the analysis and interpretations.”

Following its acquisition of Artificial Lift Performance Ltd., Meier continues, ChampionX is extending its platform to include similar software capabilities for electric submersible pumps and gas lift systems. To help production teams optimize their time, the ESP/gas lift optimization platform allows engineers to manage by exception by reviewing which wells are performing above par, at par or below par, Meier mentions, adding that it can highlight production drops or pressure changes that may warrant attention.

Power Preserver

In the Permian Basin and elsewhere, exploration and production companies are relying more on electricity to powerartificial lift and other operations. However, even the briefest power disruptions from utilities quickly switching transmission lines can cost companies production and revenue.

Such interruptions may only last a second or two, but actual downtime can be much longer because a power flicker can turn off an ESP or other electric pump, explains Ted Wilke, president of SPOC Automation.

Ben Gully, chief technologist for SPOC Grid Inverter Technologies, reviews hybrid energy systems designed to help artificial lift equipment stay on through brief power interruptions that can lead to lengthy downtime. Because they only need to provide backup power for a minute or two, SPOC says the systems improve reliability at an attractive cost.

With the pump off, fluid in the vertical column falls back to the bottom of the well, causing the ESP to spin backward in the process. Restarting the pump before this backspin stops can break the pump shaft, Wilke cautions, meaning production can be delayed as long as an hour. If the well normally produces 5,000 barrels a day, that hour of downtime can cost 200 barrels of production and corresponding revenue, he estimates.

To keep equipment running through short outages, the Trussville, Al.-based company has developed a backup power solution that relies on either capacitors, which discharge quickly, or lithium-ion batteries, which provide longer-lasting power. Housed in a cabinet smaller than a typical variable speed drive, the solution is connected to the drive’s DC segment to maintain an ample charge. Usually, the battery pack stores a few kilowatt hours of power, Wilke details.

“We are not talking about running a 100-horsepower motor for two hours,” he notes. “We would need a huge battery for that. We are talking about 30 seconds or a minute, maybe even two minutes of power as a backup system.”

The temporary backup systems can be less expensive than a typical VSD, Wilke says. For example, a capacitor unit capable of providing a burst of power for a 125-horsepower beam pump may cost around $10,000, with additional expenses for installation.

While such backups are unnecessary in places with extensive utility grids, they are being deployed to remote production sites in Kansas, North Dakota, Oklahoma and Texas, Wilke says.

High-Volume Rod Lift

Many operators are accelerating their wells’ transition from ESPs to rod lift by deploying long-stroke pumping units that can handle production volumes typically associated with a well’s third or fourth ESP, says Spencer Evans, development manager at Liberty Lift Solutions.

The vertical units, which stand 40-50 feet high, allow for increased stroke length and slower rod velocity. The combination produces higher volumes and greater pump fillage per stroke, enabling the units to lift 400-800 barrels a day with about half the strokes of a pumpjack, Evans reports. Fewer strokes translates into around 2 million fewer cycles a year and less wear on rod strings and tubing in conventional, unconventional and deviated wells, he says.

Long-stroke pumping units lift enough oil that, in many wells, they can eliminate the need to use a third or fourth ESP before moving to rod lift, Liberty Lift Solutions reports. The company says the units deliver these high volumes with slow strokes that extend rod and tubing life.

“These long stroke units have stroke lengths ranging from 291 inches to 416 inches,” he points out.

Results have been strong, Evans reports. For example, one Permian unit set to pump at a slower pace produced 500 barrels a day for four months from a 10,000-foot well. The system ran for 2.5 years before it had to be pulled because of a corroded pump barrel, Evans adds.

In Lea County, N.M., a unit with a pump depth of 9,000 feet achieved production rates of 733 barrels a day, and in Winkler County, Tx., a pump at a similar depth delivered 890 barrels a day, he continues.

A variable speed drive operates the unit and can adjust speed to account for reservoir conditions and production objectives, Evans says. Motors range from 100 to 150 horsepower, compared with 350-450 horsepower required for ESPs to achieve similar production rates, he says.

A wireless load cell can detect overspeed, vibration and load problems, shut down the system if necessary, and issue an alert through real-time digital communications, Evans assures. Hydraulics are used only to aid in rollback along a frame to accommodate a workover rig.

Rods are raised and lowered with a chain-and-sprocket assembly, which is attached to the rod string on one end and a counterweight box on the other.

Long-stroke units can cost 10%-20% more than a complete pumpjack system, Evans says, but reducing wear on rods and tubing and forgoing at least one late-stage ESP before conversion can make up the difference.

Urban Ninja

As cities expand outward and laterals increasingly enable operators to place wells in urban environments, the need for quiet and unobtrusive artificial lift equipment has grown, says Ron Peterson, principal engineer at Unico LLC. In response, the Franksville, Wi.-based artificial lift company is making its linear rod pump units even quieter by upgrading the tooth profile on their rack-and-pinion lift system’s rack. These upgrades build on noise reductions achieved by powering the units electromechanically instead of hydraulically, he mentions.

The units are popular in Australia and are replacing many traditional pumpjacks in urban areas of California and Colorado, he reports.

With their slim profiles and quiet operations, linear rod pumps have become a popular choice for urban environments, UNICO says. The units also offer built-in automation and precise stroke control to help downhole components run longer.

Like a pumpjack, a linear lift unit activates a traditional rod string and downhole plunger pump. Unlike a beam pump, it includes a slim, vertical housing that varies in height depending on the rod weight, which corresponds to well depth. Standard-duty units for shallower wells have stroke lengths ranging from 20 to 86 inches, while tandem heavy-duty units for deeper wells extend to 120 inches, Peterson describes.

The housing bolts to a standard API casing flange using a traditional rod stuffing box. An AC-powered, reversible electric servo motor, or potentially a pair of motors in deeper wells that require high torque, is mounted about halfway up the unit, Peterson continues. He says motors vary in size from five horsepower to 60 horsepower, with a combination of two on a tandem unit providing 120 horsepower.

Powered by a drive in a standard electrical box next to the pumping unit, the motors activate a rack-and-pinion system housed in an oil bath inside the unit. Motors turn the pinion, or circular gear, which moves a serrated rack up and down. A polish rod, clamped at the top of the unit, passes through the rack with each cycle. On the down cycle, the servo motors help control rod descent.

The controller can optimize speed at the surface by assessing the load on the motors and estimating liquid and gas pump fill, Peterson reports. “By adjusting the speed and acceleration independently to create a controlled motion profile, we can protect the rods, tubing and pump down hole better than a conventional pumpjack,” he says.

If a pump valve gets stuck, the linear system automatically detects the condition, then initiates a patented cleaning function that shakes the pump to remove debris, he says.

Linear rod pump costs range from $10,000 to $90,000 depending on capacity and size. The units’ simple installation, ability to reduce downhole failures and built-in automation easily justify the cost in many applications, Peterson says.

Linear ESPs

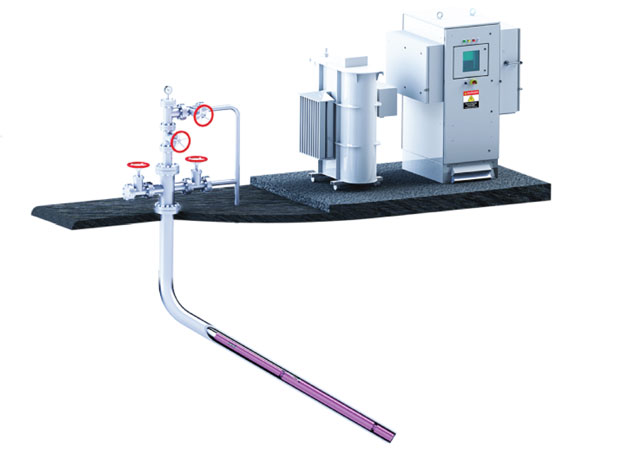

Linear ESPs (LESPs) can be an excellent choice for unconventional wells that are ready to move away from traditional ESPs, especially if their well bores have enough deviation to be hard on rod lift systems or are located in environmentally sensitive areas, suggests Kelsey Gonzalez, director of engineering for Valiant Artificial Lift Solutions. While rod lift likely will be more economical in conventional vertical or less deviated wells that produce little gas, he says LESPs can reduce the cost associated with transitioning from ESPs in unconventional shale wells.

“The price point is in the $100,000-$150,000 range versus $300,000 or more for a complete transition to rod lift,” Gonzalez details.

These savings are significant enough that Gonzalez says Valiant, through a joint venture with Ukrainian company Triol, is rolling out LESPs with some of the Permian’s biggest operators. LESP’s lower cost comes partly from less expensive equipment change outs. An ESP driver can be removed easily and an LESP driver of similar dimension installed in its place, he explains, adding that LESPs have a similar wellhead set up and use the same power cable as an ESP.

Moving from high-volume traditional ESPs to lower-volume linear ESPs can be easy and affordable because the two technologies’ ancillary equipment shares many similarities, Valiant Artificial Lift Solutions says. To take advantage of the low transition costs, many of the Permian Basin’s largest operators are testing LESPs.

LESPs are plunger-style devices powered by a variable speed drive similar in appearance to one for an ESP but with different electrical capacity and software, Gonzalez says, noting that one of the LESP units delivers 50-400 barrels a day. This unit’s drive activates the linear pump by turning a series of magnets on and off intermittently to move the plunger up and down at 17 cycles a minute. The 40-foot-long tool has a stroke length of 50 inches, Gonzalez adds. Unlike an ESP with fluid intake at the bottom of the pump, the intake on an LESP is at the top.

A typical ESP in the Permian has a lifespan of about a year and three months compared with the longest LESP field trial runtime of 440 days, although Valiant hopes to extend it up to two years, Gonzalez says.

About a decade ago, others attempted to develop and deploy LESPs in the United States with little success, Gonzalez acknowledges. Oklahoma City-based Valiant, formed in 2016, discovered promising technology in 2019 from Triol. At first, the pump was unsuccessful in Permian wells because most had harsher conditions than the more chemically simple wells in Russia where the tool was used, he recalls.

The companies re-engineered the pump to improve metallurgies, production capacity and gas handling capability so it could be installed in the Permian’s deviated wells, Gonzalez relates. Gas can be the enemy of any plunger pump, he points out, but with its intake at the top, the LESP allows more natural separation. It also includes an auxiliary gas separator to help process internal fluid before it enters the barrel.

For wells with higher levels of gas interference, some operators choose to run an additional vortex regulator under the LESP string, a device that further controls gas slugs from the reservoir by converting them into manageable bubbles and channeling them back up to the pump’s intake, he says.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 forced an emergency relocation to Poland of Triol’s plant near the Russian border and delayed U.S. rollout considerably, but the re-located plant now is operational. Permian operators interested in the concept from the start stuck with plans to continue field trials, Gonzalez concludes.

High-Flow PAGL

The amount of fluid that plunger-assisted gas lift systems can reliably bring to surface continues to increase, says Justin Lake, general manager of plunger lift at Endurance Lift Solutions. For high-volume wells, he frequently recommends a two-piece, ball-and-sleeve-style plunger with a huge bypass and flow path that allows it to fall through high-pressure gas quickly and reliably. This capability virtually eliminates the need to shut in the well during each cycle, enabling the plunger to complete more cycles and lift more fluid, he says.

This single-piece, non-threaded dart plunger can extend replacement intervals in applications that involve frequent dry impacts, Endurance Lift Solutions reports. Because its body lacks multithreaded or crimped connections, it has fewer weak points than traditional designs, the company explains.

For applications where dry impacts can cause premature plunger failures, the company has introduced a patent-pending, single-piece dart plunger, which is the first of its kind with no threaded connections on the plunger body, Lake says. Eliminating the multithreaded and crimped connections traditionally employed minimizes potential weak points in the plunger, enabling it to run longer. A unique adjustable clutch mechanism also contributes to the tool’s long run life, he adds.

To improve durability, plungers can be treated with boron carbide (B4C) to strengthen their surfaces’ resistance to corrosion, abrasion and mechanical wear, Lake continues. In field trials, the treatment has extended the run time of sleeve and dart-style plungers as much as four times, he reports.

This surface treatment can be particularly helpful in problematic sandy or paraffin-producing wells, Lake suggests. In these applications, plungers tend to wear out quickly or get stuck at the surface, requiring regular hot oiling. In contrast, B4C-treated plungers have a proven history of long run lives, even in challenging conditions, Lake says.

According to Anthony Mason, Endurance’s senior vice president, the surface treatment also can prolong gas lift mandrels’ life in difficult well environments, such as ones where hydrogen sulfide is present.

“We have also successfully used the treatment on other artificial components, including rod pump parts, motor valve trim kits and ESP stages,” Mason reports. “Along with improvements in equipment designs, it is helping reduce downtime and the costs associated with replacing equipment.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.