Drilling Technology

Operators Test New Concepts, Redefine Best Drilling Practices In Permian Resource Plays

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

The Permian Basin’s stacked pays and favorable economics make it the choicest real estate in the world for developing oil-rich horizontal resource plays, as evidenced by the number of big-dollar acreage acquisitions all across the basin in recent months. As companies step up drilling operations, they are continually applying lessons learned and redefining best practices to systematically optimize horizontal drilling performance from one well to the next.

But it is not only a matter of identifying the best technologies and techniques to drill a given horizontal lateral on a particular pad; it also is critical to plan practices and strategies for optimal full-field development of an entire acreage position with multiple stacked targets at varying depths that will take years to fully drill. In such a target-rich environment, the macro is no less important to long-term success than the micro.

The abundance of prospective formations and intervals provides plenty of world-class drilling options, but also adds development complexities, confirms Clay Gaspar, chief operating officer and senior vice president for Tulsa-based WPX Energy. For example, he says, his company’s Stateline Field in the heart of the Delaware Basin along the state line between Loving County, Tx., and Eddy County, N.M., has as many as 13 potential zones to drill.

“And it continues to grow,” he marvels. “We look at the subsurface as one giant cube, with lots of layers and subparts. How do you ultimately drill all the parts and depths of the cube? We are looking at vertical and horizontal spacing, landing zones, staggering, sequencing and many other variables.”

Another challenge is avoiding the numerous vertical wellbores that already exist in a basin that has had active drilling for nearly 80 years. “The Permian is a unique animal because of all the vertical wells that go deeper than the target horizons,” explains Aaron Felton, senior manager of drilling and completions in the Permian Basin for Encana Corp. “They were drilled a long time ago, and in some cases there are not a lot of details.”

He says Encana has spent a great deal of time acquiring knowledgeable, updated anti-collision processes that incorporate magnetic variations into survey data to avoid contacting old vertical bore holes with new horizontal laterals. One of the things that Encana did was create a “well planner role,” a person assigned to take all the surveys in an area and plot them into a three-dimensional map, Felton details.

“She lays in the targets, but she also lays in all of the zones in the bench,” he states. “She creates ‘ghost’ well bores, so the real estate in 3-D exists. If you do not preplan, you can be in a real bind when you go back to drill another zone. It is incredible when you look at the subsurface of a big pad to see just how many wells can be in it.”

Well Spacing Test

As part of its ongoing delineation of optimal well spacing in its Delaware Basin operations, WPX Energy has dedicated three rigs to a nine-well spacing test in the Upper and Lower Wolfcamp A zones. Gaspar says the project is designed to validate 80-acre spacing in both Wolfcamp A zones, which would result in 16 wells per drilling spacing unit.

“This test will give us a much better understanding of the proper vertical and horizontal spacing,” he states. “The information we get from this test could be very important to our development plans.”

All nine test wells had been drilled and fractured as of mid-March, and WPX Energy was drilling out plugs and preparing for flowback with first production expected in April. “We are anxiously awaiting a big chunk of production,” Gaspar adds. “It is an interesting balance to test the science and the right spacing, but you also need to get the wells on line to add value to the company.”

Moving Closer In The Delaware

During the fourth quarter, WPX dedicated three rigs to a nine-well spacing test in the Upper and Lower Wolfcamp A zones in the Delaware Basin. The project is designed to validate 80-acre spacing in both the upper and lower intervals, which would result in 16 wells per drilling spacing unit. Initial flowback on the wells is expected to start in late March, with first sales in April.

The purpose of the nine-well test is to explore a second landing zone in the Wolfcamp A and validate denser well spacing in the Upper and Lower Wolfcamp A, according to Gaspar. “We are trying to make sure we gain critical knowledge from this unique opportunity. We will end up with fully-bounded wells in the upper and lower landing zones while we test vertical and horizontal spacing. Some of the early data have been very positive,” he relates. “We hope the results ultimately lead to opportunities to increase recoveries, improve development efficiencies, limit future interference from offset wells, and guide stimulation design enhancements.”

Gaspar says the test will help WPX Energy determine the best well spacing across its Delaware Basin leasehold, particularly in developing multiple reservoir intervals and designing frac treatments with the other nearby well bores and intervals in mind.

“You want the shadow of one well’s stimulated reservoir volume over the shadow of another well’s SRV, so that there is slight interference between wells,” Gaspar continues. “But you do not want to have significant overlap because that could create too much interference and degrade production and recovery performance.”

Gaspar says WPX Energy typically drills two-four wells a pad, accelerating information gathering and time to production as well as allowing for the use of zipper frac techniques in multiple laterals.

“You hope to energize the formation side to side,” he explains. “We use zipper fracs in two or three wells at a time and then move on to the next pad.”

According to Gaspar, since the beginning of the year, three of WPX Energy’s Delaware Basin rigs have been drilling what the company calls “extended-length” laterals that extend between 1.5 and 2.0 miles. About 40 percent of the wells on the company’s 2017 drilling schedule for the area are extended-length laterals. “We expect to increase our average lateral length by 35 percent this year, to more than 6,200 feet,” Gaspar says.

The company drilled its first Wolfcamp X/Y delineation well last year–a one mile-long lateral–in only 17.5 days, which was its best drilling time to date in the basin. However, Gaspar says the preference is to drill extended-length laterals whenever possible, although lease limitations sometimes restrict lateral lengths to around 5,000 feet.

“Drilling in other basins, such as the Williston in North Dakota, the standard lateral length is two miles, and we have drilled three mile laterals in the Bakken,” he maintains. “We are very comfortable drilling two miles down and two miles out.”

Accordingly, Gaspar reports that WPX Energy began spudding its first extended-length laterals in the Delaware Basin late last year, including the first of four two-mile laterals scheduled in CBR sections to drill 6-7 pad, the same lease on which it is conducting well spacing density testing.

Remaining In Zone

Gaspar says WPX Energy has “moved the needle the last couple years” in how it geosteers wells to remain in the target zone while drilling the lateral section.

“It is important to find the right landing zone and keep it in the window,” he claims. “With a 20-foot window, our guys believe they can drill as fast as they can go. It takes really good dialogue between the geosteering team, the geologist and the drilling engineer. There is natural technical tension between those groups. The geologist wants the tightest, most specific window possible. The driller wants a wider window. The geosteering guys are sitting there 24 hours a day, seven days a week, looking at real-time feedback and making corrections.”

While gamma ray testing is continuous as the lateral is drilled, Gaspar says WPX takes a directional survey every 200 feet.

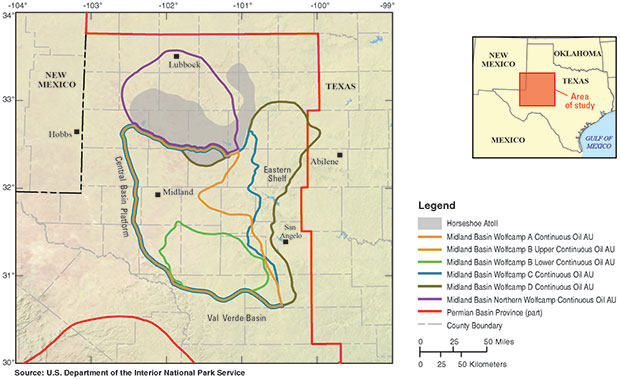

Extent of Wolfcamp Shale Assessment Units

The petroleum industry divides the Wolfcamp Shale in the Midland Basin into four stratigraphic units, based on petrophysical log signatures and landing zones for horizontal wells, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The uppermost is labeled the Wolfcamp A, followed by the underlying Wolfcamp B, C and D units, respectively. The survey says the eastern margin of the Wolfcamp Shale deposition prograded westward through time, as indicated by the larger depositional areas delineated in the C and D assessment units when compared with the A and B assessment units. The USGS projects the Wolfcamp Shale play holds as much as 20.0 billion barrels of oil, 16.0 trillion cubic feet of associated natural gas and 1.6 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.

“It is amazing that the geosteering team can take that information and knock it into a three-dimensional map to know which direction the bit is headed,” he explains. “It is easy to fall into the trap of oversteering. You have to nudge it, then wait and be patient. Think about it: We are drilling a couple of miles deep and then a couple of miles laterally and trying to hit a window the size of a Suburban on the other end. It looks like a hair from that distance. It is pretty remarkable.”

Gaspar says his company has done a lot of work to determine the lateral orientation that will maximize the angle at which the wellbore intersects the formation’s natural fractures. “In the San Juan Basin, we drill wells on a 45-degree northwest-to-southeast orientation,” he explains. “It is less critical in the Permian Basin because of the pressure.”

He adds that he has no strong preference for either a toe-up or toe-down design in the Permian Basin, but says WPX Energy generally prefers a toe-up lateral to help optimize production.

Gaspar relates that WPX Energy uses standard PDC bits, although he admits it is different drilling in the Bone Spring formation compared with the Wolfcamp D zone. He notes that the company uses a water-based mud system in its wells’ shallower sections because it can be recycled and is cost-effective, but uses oil-based mud when drilling the lateral.

WPX recently has closed on what it calls the “Panther” acquisition, which consists of 18,100 net acres in Texas’ Reeves, Loving, Ward and Winkler counties and includes 920 gross undeveloped locations in the Delaware Basin’s geologic sweet spot, Gaspar reports. With that acquisition, WPX Energy now has seven rigs operating and plans to drill more than 100 wells in 2017 in its 120,000 net acre Delaware leasehold.

He cites three components to success with best practices: One is to really watch costs. The second emphasizes well performance, and not only initial production, but also ultimate recovery. The third focuses on organizational culture.

“You have to have a strong bias for action,” Gaspar reflects, listing attributes such as accountability for constant improvement, a will to keep fighting for the next opportunity, and humility to recognize when someone else seems to have figured out a better solution.

“I think technology in our industry is greatly underappreciated by those outside the industry,” he adds.

‘Mega Pad’ Development

Encana operates exclusively in the heart of the Midland Basin, the largest of the Permian sub-basins, with a cluster of leaseholds across a half-dozen West Texas counties, including Midland, Howard, Martin and Glasscock. Felton says the number of wells the company drills on a given pad varies because its acreage is not contiguous.

“It may be as few as two or three, although we try to squeeze as many wells as we can per section,” he maintains. “It depends on what your backyard looks like.”

If the yard is big enough, it may accommodate a scaled-up development concept that Encana calls the “mega pad.” The company’s first mega pad–the RAB Davidson Pad in Midland County–is capable of holding 64 wells on one large, single pad sized on the order of eight football fields long by two football fields wide.

Scaling Up In The Midland

Sized on the order of eight football fields long by two football fields wide, Encana Corp.’s RAB Davidson ‘mega pad’ in the Midland Basin is capable of holding 64 wells. Encana initially drilled 14 wells last year with an average lateral length of 8,630 feet using four rigs located side by side, and then brought the four rigs back earlier this year to drill 19 additional horizontal wells on the upsized pad. The 19 new wells were undergoing completion operations in March.

“Think about the pad as a big rectangle,” he explains. “We lay in the wells. Unlike other companies, we bring in four rigs to do the first pass. These four rigs sit side-by-side drilling four-five wells, each with a reserve pit behind it.”

When those four rigs finish drilling, four frac fleets move in and simultaneously complete the wells to minimize cycle times. When it is time to drill the next bench, the four rigs return and rig up to the left of the original well clusters and repeat the process, each drilling four-five more wells while utilizing the same reserve pits. “That way, we do not have to increase our footprint and can utilize the same infrastructure for facilities and production,” Felton explains.

When the rigs finish drilling that row after the second occupation (~32 wells), they can flip 180 degrees and do the same thing on the pad’s other side, drilling 32 more laterals in the opposite direction in the third and fourth reoccupation of the same pad, Felton describes. Thus, 64 wells can be drilled on a single pad to minimize the surface footprint and maximize efficiencies across multiple disciplines.

Encana initially drilled 14 Wolfcamp wells on the RAB Davidson mega pad in the first quarter of 2016, and then returned and drilled 19 more in the first quarter of 2017. The 19 wells drilled during the second occupation were being completed in late March. As predicted, Felton reports, cycle times dropped during the next batch with the benefit of lessons learned from the first occupation.

“The mega pad helps further drive operational and logistical efficiency gains. It lowers well costs, minimizes surface footprints and reduces nonproductive time,” Felton explains. “It also accelerates the drilling learning curve by having such a large number of wells on one pad, and eliminates the need for future infill drilling.”

Lateral Lengths

Lateral lengths mainly depend on acreage positions, Felton claims, but also are driven by completion capabilities. “The routine lateral now exceeds 5,000 feet, and getting from 5,000 to 10,000 feet is not that big a deal. But the optimal length is driven by completions. We use mostly plug-and-perf completions in the Permian Basin. Drilling out the plugs on two-mile plus laterals pushes the limits of the workover rigs and coiled tubing units.”

Felton says Encana has some 11,000-foot laterals, but usually does not extend much longer because of the associated completion expense. He notes that Encana bottom-hole drilling assemblies match high-performance mud motors with PDC bits to drill lateral sections, which are typically 8½ inches in diameter. “PDC bits are evolving on a weekly basis,” he says. “The bit companies’ designs have to balance speed with durability to keep or increase market share.”

Felton adds that the company occasionally uses an “ugly duckling,” a hybrid PDC and roller-cone bit, to drill the curve sections in areas where build rates are poor.

Encana orients its laterals north-south, based on the Permian’s stress planes, and uses only water-based mud systems for all well sections. “We use what is referred to in the Permian Basin as ‘Spraberry slop’ mud to get to the intermediate casing point,” he explains. “Most companies use an oil-based mud to drill the lateral, but we use a high-performance water-based mud system. It is more environmentally friendly for the guys who are handling it and it is not as expensive. You also can reuse it from one well to another.”

Felton notes that Encana uses “spudder rigs” to set the surface casing, which is often only 400-500 feet deep, in advance of drilling the lateral. Casing sizes are typically 13⅜ in the surface hole, 9⅝ in the intermediate section and 5½ inches in the lateral. While bigger rigs can set surface casing at a relatively small incremental day rate cost, he maintains, using dedicated smaller units for that task allows crews on both the spudder rigs and bigger ones to keep repeating the same tasks, thereby improving efficiency for all the well’s segments.

“We are drilling horizontal wells from spud to total depth in fewer than 10 days,” he lauds.

Real-Time Geosteering

Of course, one critical element of drilling 10,000-foot laterals is the ability to stay within the targeted zone. “I have the geosteering team on my speed dial,” Felton quips.

To assist in real-time geosteering decision making, the data from measurement-while-drilling tools with gamma ray are uploaded to Encana’s command center in Denver, which is manned 24/7.

According to the company, all of Encana’s U.S. wells, including those in the Permian Basin, are monitored by the geosteering team in Denver, which watches every well in real time and has the capability to order course corrections. As of mid-March, the center was monitoring data from the eight rigs Encana was operating in the United States, including five in the Midland Basin.

“The target boxes are tight in the Permian wells, maybe only 20 feet up and down,” Felton describes. “I cannot say a well never gets out of the target, but we stay in the target zone at least 90 percent of the time.”

Felton says he subscribes to the “limiter theory concept” first adopted by Exxon. “You want to make the most footage per day,” he says. “You find that one thing that limits you from making the most footage and you work to correct that one thing. Then you find the next thing and work to improve that instead of trying to attack a number of different issues at the same time.”

The company operates a fairly new mixed fleet of 1,500-horsepower Helmerich & Payne and Trinidad rigs, all with modernized top drives and 7,500-psi standpipe systems, Felton notes. He says all have extended skid packages that allow the rigs to be skidded up to 200 feet. All the rigs also have dual-fuel engines, although he adds that Encana is not using natural gas at present because gasoline and diesel are so affordable.

Felton notes the rig’s substructure is situated so the rig can move right up to existing wells. “That is another lesson we have learned to reduce our surface footprint and reoccupy preexisting pads,” he offers.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.