Crude Oil Exports

Port, Pipeline Upgrades Accelerate Rapid Growth In U.S. Crude Oil Exports

By Colter Cookson

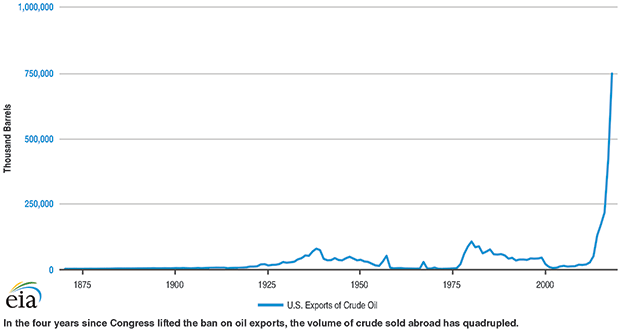

While the amount of crude oil the United States exports varies from month to month, the trend continues upward. In the four years since Congress lifted the ban on oil exports, outbound cargos have quadrupled.

This rapid export growth reflects the slower but equally impressive ascent in total domestic oil production, which U.S. Energy Information Administration data shows has doubled in the past 10 years. Although publicly traded companies increasingly emphasize fiscal discipline and free cash flow more than production growth, EIA predicts U.S. production will reach 13.3 million barrels a day in 2020 and 13.7 MMbbl/d in 2021.

Much of the incremental production is coming from unconventional plays, such as the Permian and Bakken, that generally produce light crudes, but most U.S. refineries are designed for heavier grades. While those facilities are doing what they can to take advantage of the domestic bounty, production is outpacing their ability to add capacity.

Producers, midstream companies, ports and fleets are working together to move this excess light crude to European and Asian markets, where it often commands higher prices. This has tied U.S. crude prices more closely with those in other parts of the world.

“There is little doubt that exports now have a huge impact on U.S. domestic prices,” RBN Energy argues. “In 2019, 2.9 MMbbl/d of crude oil was exported, up from 2.0 MMbbl/d in 2018 and 1.2 MMbbl/d in 2017. Pipeline feed gas for liquefied natural gas exports now is up to 8.0 Bcf/d and growing fast. More than half of all domestically produced propane is exported. The pace of exports now is every bit as important as changes in stocks in influencing the level of U.S. spot oil, gas and natural gas liquids prices.”

New Connectivity

Most U.S. crude oil exports ship from Gulf Coast facilities, so pipeline capacity to the ports there influences how quickly exports can grow. Midstream companies say they are doing what they can to ensure there is enough capacity without overbuilding.

In the four years since Congress lifted the ban on oil exports, the volume of crude sold abroad has quadrupled.

“The demand for exports is robust, but we need more infrastructure to meet it,” says Kelcy Warren, Energy Transfer’s chairman and chief executive officer. “We are connecting this new infrastructure to existing pipeline networks that maximize shippers’ market options.”

Late in 2019, three Permian-to-Gulf-Coast pipelines entered service: Energy Transfer’s Permian Express 4, a 120,000 bbl/d expansion of a pipeline from Colorado City, Tx., to Nederland, Tx.; Plains All American’s 670,000 bbl/d Cactus II, which delivers to the Corpus Christi, Tx., area; and Enbridge and Phillips 66 Partners’ 900,000 bbl/d Gray Oak Pipeline, which also delivers to Corpus Christi.

These pipelines give the Permian Basin enough take-away capacity through at least 2020, S&P Global Platts said in August. The analyst points out that the pipelines have helped narrow the price spread for West Texas Intermediate at Midland versus the Magellan East Houston Terminal.

More pipelines are coming. In fact, Permian take-away capacity already may be bolstered by the 600,000 bbl/d EPIC Crude Pipeline, which was scheduled to come on line in January. In 2021, the Wink to Webster Pipeline should increase take-away capacity to the Gulf Coast by at least 1.0 MMbbl/d.

The Bakken

Like the Permian Basin, the Bakken is undergoing a much-needed infrastructure expansion. In July, RBN warned that many of the Bakken’s incremental barrels would need to be shipped by rail until new pipelines enter service. “As more barrels transition from pipeline pricing to rail pricing, Bakken differentials could widen as well, moving in tandem with the higher cost to transport crude via rail,” RBN said.

“It is remarkable how much Bakken production has grown since DAPL entered service in June 2017,” reflects Warren. “The folks at exploration and production companies are brilliant. I am proud the pipelines we build help them get their oil, gas and liquids to profitable markets.”

Until recently, the ample capacity on the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and the Bakken’s robust rail infrastructure limited the need for pipeline expansions, RBN observes. “The secondary issue (limiting) pipeline development out of the Bakken was the experience Energy Transfer faced completing DAPL. There was significant political and social backlash to the project, and a number of legal hurdles had to be overcome to get it approved,” the analyst notes.

Despite those obstacles, new projects are moving forward. These include Liberty Pipeline LLC, a joint venture between Phillips 66 and Bridger Pipeline LLC that is building a 24-inch pipeline from Guernsey, Wy., to Cushing, Ok., from which shippers can access the Gulf Coast. Published reports put the pipeline’s capacity at 350,000 bbl/d.

“The Liberty Pipeline is an important undertaking to ensure oil from Wyoming, the Rockies and the Bakken can get to markets in the United States and around the world,” Bridger Pipeline President Hank True said in announcing the pipeline’s construction. “Our commitment to the Liberty Pipeline will give producers confidence to grow oil production in these important regions.”

With new or upgraded pipelines bringing more crude oil to the Gulf Coast for export, midstream companies are investing in more efficient ways to load crude carriers. Energy Transfer is a case in point. The company reports it plans to deepen waterways at its terminal in Nederland, Tx. It also is building a pipeline linking the terminal to a port on the Houston Ship Channel that has five deepwater ship docks.

RBN highlights as the other major proposal Energy Transfer’s plan to expand DAPL’s capacity from 570,000 bbl/d up to 1.1 MMbbl/d. DAPL connects with the Gulf Coast through the Energy Transfer Crude Oil Pipeline, which runs from Patoka, Il., to Nederland, Tx.

The DAPL expansion only requires three new pump stations and upgrades at existing stations, and Warren expresses hope it will secure approval on schedule. If so, the additional capacity should enter service in 2021.

Export Capacity

As pipelines move more oil to the Gulf Coast, local ports’ ability to store and load it onto ships is the next potential cap on exports. But for now, analysts say that bottleneck is only theoretical.

“Fears of a bottleneck that would impede U.S. exports have not materialized,” a Jan. 20 article from Reuters assesses. It credits the relief in part to new storage and other upgrades at Corpus Christi, which Genscape says added more than 5.0 million barrels of storage capacity last year.

In a list of its top 10 predictions for 2020, RBN suggested that crude oil export capacity would be adequate for at least four or five years. In fact, it says there is enough capacity for ports to compete on cost. “Exports from Corpus Christi have been ramping up at the expense of Houston, Beaumont, Tx., and other Gulf Coast terminals. That means those other terminals have capacity on their hands,” RBN said.

Several companies are seeking approval for projects that would increase U.S. export capacity, but their goals are to streamline exports and reduce costs rather than relieve bottlenecks. Many U.S. export terminals are on inland ports that only can be reached through channels, and none of these channels are deep enough to accommodate the largest crude carriers when fully loaded.

To compensate, carriers take on a partial load at the dock, move into the Gulf and wait while smaller ships ferry oil to them from the ports. This process, called reverse lightening, costs time and money. Exports would be more efficient and therefore competitive if U.S. ports could fully load very large crude carriers (VLCCs), the second-largest tanker class.

For now, the United States only has one port with that capability: the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), which is 20 miles from Port Fourchon, La., in 110 feet of water. LOOP opened in 1981 as an import facility. It still performs that function, but in an article on Houmatoday.com, LOOP President Terry Coleman estimates that 40 percent of the vessels making deliveries there leave full of U.S. crude.

The U.S. Maritime Administration has received at least four applications to build deepwater ports with a total capacity of 6.3 MMbbl/d. Proposals include the Sea Port Oil Terminal (SPOT) 30 miles off the coast of Brazoria County, Tx., a joint venture between Enterprise Products Partners and Enbridge with a capacity 2.0 MMbbl/d, and JupiterMLP’s Offshore Loading Terminal six miles off the coast of Brownsville, Tx., which can handle 1.0 MMbbl/d.

Analysts say only a fraction of those terminals will be built. In fact, shortly after announcing SPOT, Enbridge withdrew its application to build the Texas Crude Oil Loading Terminal, which also would have had a capacity of 2.0 MMbbl/d.

A Major Player’s Efforts

Like many of its peers, Energy Transfer says it is looking for ways to accommodate VLCCs. For example, it is planning to connect VLCCs to its Nederland terminal on the Sabine-Neches Waterway between Beaumont and Port Arthur, Tx., which has more aboveground storage capacity than any other single-owner facility in the United States. Energy Transfer says this would provide customers increased flexibility in their efforts to export crude to global markets.

With a diverse supply base that includes the Permian Basin, Cushing and Canada, as well as connectivity throughout the Gulf Coast, Nederland offers versatility to both shippers and buyers, Warren says. He predicts the VLCC project will take at least two and a half years.

In addition to the VLCC project, Warren says Energy Transfer is part of a public/private partnership working to deepen the shipping channel leading to Nederland. “The average depth there is 40 feet, which limits how fully we can load ships. We are hoping to increase the depth to 45-50 feet,” he reports.

Through a merger with SemGroup, Energy Transfer acquired a terminal on the Houston Ship Channel with five ship docks and seven barge docks. “SemGroup is a well-run company with great assets in Canada, the Rocky Mountains, and the Mid-Continent, but the Houston terminal was its biggest draw,” Warren says. He mentions the facility’s storage tanks can hold 18.2 million barrels of crude, and there is plenty of land to add more as needed.

To give the recently-acquired terminal greater access to crude oil supplies, Energy Transfer plans to build a pipeline to it from Nederland. The Ted Collins pipeline will be able to move 500,000 bbl/d and should come on line next year, Warren describes.

“Connectivity between the two terminals will provide immediate access to 1 MMbbl/d of existing crude oil export capacity, which we plan to expand to more than 2 million barrels,” he says.

LNG Exports

The United States now is the world’s third-largest LNG exporter, behind only Qatar and Australia, EIA reports. From January through November of last year, the agency says, U.S. exports averaged 4.8 Bcf/d, 61 percent higher than in 2018.

As of late January, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission indicates there are six LNG export terminals operating in the Lower 48, with eight more under construction. Several others have been approved but have yet to reach the final investment decision stage.

Energy Transfer’s Lake Charles LNG project in Lake Charles, La., is the only fully permitted project waiting for a final investment decision. Warren points out that the project involves converting an import facility built decades ago. “We already have docks, refrigerated tanks and other assets needed to handle LNG, so the terminal has a cost and time advantage,” he says. “It also benefits from existing pipeline connectivity that can provide diverse and robust supply.”

Given those strengths, Warren expresses optimism about Lake Charles LNG’s future. “Recent progress in trade negotiations with China, one of the biggest LNG importers, may help us secure enough customers to push the project across the finish line,” he offers.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.