Treasure Trove Of Targets Giving Permian Independents Ample Development Opportunities

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

From the Avalon to the Bone Spring, San Andres, Spraberry, Wolfcamp and Barnett—that’s right, the Barnett!—Permian Basin operators are finding ample opportunities to take their production volumes and overall business performance to new heights.

In the Delaware and Midland sub-basins, Devon Energy Corp., HighPeak Energy and Matador Resources are applying innovative drilling and completion technologies to develop a treasure trove of multiple zones stacked high in multiple formations. On the Northwest Shelf, PEDEVCO Corp. is developing a unique play targeting the San Andres in Chaves and Roosevelt counties, N.M. Meanwhile, on the Central Basin Platform sandwiched between the Midland and Delaware, Elevation Resources LLC, is busy developing the Barnett Shale.

Steve Pruett, president and chief executive officer of Midland-based Elevation Resources, admits people do a double-take when he tells them he is drilling in the Barnett Shale.

“You are drilling in the Fort Worth Basin?” is the frequent response. “No, I tell them, our Barnett play in the Permian Basin,” says Pruett, who is also chairman of the Independent Petroleum Association of America. “We drilled the Barnett discovery well in 2016.”

Elevation previously held acreage in Lea and Eddy counties in New Mexico and Reeves and Ward counties on the Texas side of the Delaware Basin, as well as assets in the southern Midland Basin. But then it drilled the discovery well in Andrews County, Tx.

“We had enough encouragement from a vertical test and a core that we decided to give the Barnett a try. We sold our other assets, and now we are operating exclusively in Andrews County,” recalls Pruett, who reports that Elevation Resources is drilling its 52nd Barnett Shale well in Andrews County.

So what is the Barnett Shale?

“It is silty shale interbedded with siltstone and limestone layers,” Pruett explains. “It is a Mississippian-aged rock. It is the same formation that is called the Meramec in the SCOOP and STACK plays in Oklahoma. It is deeper than the Wolfcamp, Bone Spring and Spraberry formations being developed in the Delaware and Midland basins.”

The Barnett is only the latest in the stacked pays that have made the Permian Basin the nation’s most prolific oil-producing province, accounting for 40% of the nation’s oil and 15% of its natural gas.

Drilling Down

“We drill through the Wolfcamp, San Andres, Atoka, Strawn and Upper Barnett before we finally get into the Meramec,” Pruett states. “Below the Barnett is the Woodford and the Devonian carbonate, which Elevation previously developed horizontally.”

It took Elevation Resources several years to de-risk the play, Pruett says, but its success has brought a number of other companies into the Central Basin Platform to exploit the Barnett Shale.

Elevation Resources is drilling its Barnett wells to an average vertical depth of 10,500 feet with one- to two-and-one- half-mile laterals, according to Pruett. He notes that the Barnett is as deep as 11,000-12,000 feet in the Midland and up to 13,000 feet in the Delaware Basin.

Elevation’s Barnett wells initially produce 70%-80% oil, although over time, the ratio averages out to about 50/50 oil- gas, Pruett continues. He says the company’s production averages 56% oil and 79% percent liquids with 1,350 Btu gas.

Pruett notes that all liquids are not created equal, however. He says NGL prices are currently $22 a barrel, while oil is bringing prices in the low $70 range.

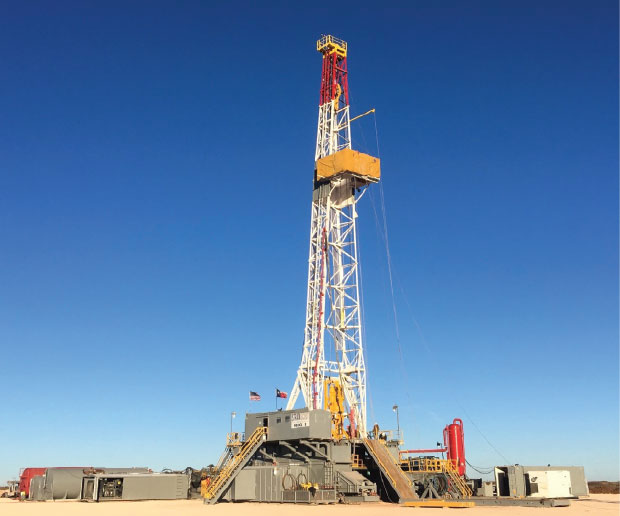

Elevation Resources LLC is drilling its 52nd Barnett Shale well in Andrews County on the Texas Central Basin Platform. Elevation Resources’ Barnett wells typically average 56% oil and 79% liquids with 1,350 Btu gas.

One advantage to Elevation’s current play is a “plethora of gas processors and plenty of pipeline takeaway capacity. Between Odessa and Andrews, there is great service and infrastructure,” Pruett contends. “It is a good place to operate.”

Elevation’s game plan for the rest of the year is to keep running one rig and half a frac spread, he reports. One concern, of course, is declining natural gas prices, which currently nets “near zero” when paying compression and processing fees.

Pruett adds that he is proud of his team in getting ahead of the curve in exceeding anticipated U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rules regarding carbon dioxide and methane emissions, including investing in thermal-imaging cameras.

“We have done a lot of good housekeeping and use third-party certification,” he points out. “We are also converting gas pneumatic valves to air pneumatic valves. That essentially eliminates any methane emissions. We are not flaring any gas on a normal basis. Normally, the only time you see flaring in the Permian these days is when gas gatherers are having trouble with compression. I encourage everyone to get ahead of the methane emissions rules.”

Multiple Stacked Pays

Nowhere are the opportunities for multiple stacked pays more prevalent than the Delaware Basin, which straddles several counties in West Texas as well Lea and Eddy counties in New Mexico.

The primary zones are the Avalon (Leonard), Bone Spring and Wolfcamp, according to John Raines, vice president for Devon Energy’s Delaware business unit. But he notes there are multiple landing zones within each formation. In fact, he says there can be as many 44 wells per section.

Devon announced in the first quarter that its Delaware Basin production had increased 5% year-over-year to an average 415,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day (51% oil). During the quarter, Devon operated 16 rigs and four completion crews, resulting in 42 gross wells placed on line across the company’s 400,000 net acres in the basin.

No doubt, the headline for Devon in the first quarter was its Exotic Cat Raider development in the Todd area in Lea County. “That is the best rock in North America,” Raines proclaims.

As a background, Devon drilled the Boundary Raider wells a few years ago in the Bone Spring Sand. “Those were the two most prolific wells ever drilled in New Mexico,” Raines relates. “One produced almost 13,000 boe/d.”

The Exotic Cat Raider project consists of six wells drilled with three-mile laterals in the Upper Wolfcamp, two of which are in the same area as the original Boundary Raider wells. Raines says the six-well project has exceeded predrill expectations, with the best well reaching as high as 7,200 boe/d.

“It is too early to know what these wells can produce before they start declining,” he adds, “but I am confident they will surpass 2 million boe.”

Devon has drilled more than 1,000 wells in the Delaware and will drill approximately another 225 wells this year. “We are always trying to get better,” Raines says. “Our team learns from each well we drill and complete.”

Devon’s completion design targets 2,500 pounds of frac sand per foot in the Upper Wolfcamp, “We continually strive to get better in stage and cluster architecture and dial in our sand volumes,” Raines explains.

Appraisal Process

Part of Devon’s success, according to Raines, is its appraisal of a formation before it enters the development phase. Its development also utilizes existing infrastructure most of the time, whether third-party or Devon’s own gathering systems.

“We have multiple areas, so it helps to lay out a multiyear plan,” he offers. “We want our gathering systems running at or near 100% capacity. That way we are not overbuilding and can keep our infrastructure spending down.”

Raines maintains there are downstream constraints, however. “We need more pipes to get the gas out of the basin,” he contends. “Another pipeline, the Matterhorn, is expected to come on line later next year. It is needed. If you look at spot gas prices, the Permian is discounted. You need to get the gas to market. Devon is lucky to have firm transport and price protection for the vast majority of its volumes. But as prices come down, other operators that don’t have the same protection may have to pay someone to take it.”

In the Delaware Basin, Devon Energy has completed the Exotic Cat Raider development in the Todd area in Lea County, N.M. With three-mile laterals targeting the Upper Wolfcamp, the six-well project has exceeded predrill expectations, reaching as high as 7,200 boe/d.

Devon operates in Loving, Winkler and Reeves counties in Texas as well as Lea and Eddy counties on the New Mexico side of the state line.

“At Devon, we do not get over our skis,” Raines explains. “It is very important that we understand our rock. We have a very intentional appraisal program that looks out two-three years. When we get ready to develop, we are confident of our rock, the landing zone and the proper spacing. For example, we’ve found that some zones within the 1st Bone Spring, 2nd Bone Spring and Avalon ‘talk to each other’ and need to be developed together.”

So how does Devon appraise new zones? “We have seismic on 95% of our assets,” he states. “We are just now starting to develop the Deep Wolfcamp, but that work started four years ago. We started doing inversion of our seismic data to make it sharper. That is like comparing your television 15 years ago to 4K high-definition TV today. We also utilize a petrophysical model that we’re always improving. When we drill one well, we will drill deeper to take a core of the Deep Wolfcamp. We will drill one well to validate it is what we think it is, and then we will drill multiple wells.”

Raines says Devon may at times drill only two wells on a pad, but it will return later to ultimately drill as many as 8-12 wells on a pad, giving the company the ability to use existing facilities. “That allows us to fully develop the reservoir with a minimal increase of our facilities’ footprint,” he remarks.

Companywide, Raines says Devon has a 10-year inventory of 4,500 drilling locations, 55%-60% of which is in the Delaware Basin. He notes that does not take into account the deeper Woodford and Barnett, or other formations as the company continues to explore the opportunities the multiple stacked pays offer in the Delaware.

Location, Location, Location

Like selling real estate, location can mean everything in drilling oil wells. Fort Worth-based HighPeak Energy operates in the northern Midland Basin, with acreage in Howard, Borden and Scurry counties in Texas. Mike Hollis, president of HighPeak, says over 90% of the company’s 113,500 acres are located in Howard County and southern Borden County, which offers a number of advantages.

HighPeak went public about three years ago and has since more than doubled its acreage position. “Our acreage doesn’t have as much associated gas,” Hollis relates. “Our first-quarter 2023 production of 37,000 net boe/d (~50,000 boe/d gross) was 85% oil and 94% liquids. So our economics are dramatically different than our peers because of our high oil weighting. We had a 55% higher margin than our average peer in the first quarter.”

That has allowed HighPeak to enjoy remarkable growth, going from about 3,100 boe/d to nearly 40,000 boe/d since it went public in August 2020.

HighPeak Energy’s acreage position in the northern Midland Basin produces mostly oil that is heavier than crude produced in the central Midland and Delaware basins, giving it an economic advantage. The company’s 37,000 net boe/d (~50,000 boe/d gross) of production in the first quarter was 85% oil and 94% liquids.

HighPeak’s oil is heavier, too, at 35-38 degree API gravity compared with 40-42 degrees gravity in the central Midland Basin and 43-44 degree in the Delaware Basin, according to Hollis.

“That is an advantage because refiners like to blend it with what they are getting from the Delaware Basin,” he explains.

HighPeak’s acreage is in two large contiguous blocks, allowing the company to build infrastructure in production corridors to handle water as well as oil and gas along with large tank batteries. Because of that, Hollis says HighPeak can be more efficient.

Much of HighPeak’s acreage is within a few miles of the Delek Refinery in Big Spring, Tx. He notes that Delek markets “the vast majority” of HighPeak’s oil production, thus reducing marketing and transportation costs.

Another advantage is a sand mine located between HighPeak’s two blocks.

“We used to have a 125-150 mile round trip to get our sand,” Hollis continues. “Today, we use 100% local wet sand. Now, we are trucking only 10-12 miles per round trip to get sand. Which can save us about $300,000 a well.”

Using local, less expensive sand also means HighPeak can use more sand in its fracs. “We average 2,200 pounds per foot and 40-45 barrels of fluid per foot,” Hollis adds, noting the company is recycling roughly 85% of its produced water.

HighPeak also has built a substation in northern Howard County, which means it can use electricity to operate some of its drilling rigs. That provides another substantial savings.

As part of that substation and overhead electric distribution lines project to power its electric drilling rigs and field operations, Hollis says HighPeak is building an 80-acre, 10-megawatt solar farm to help support its electrification efforts. The Flat Top solar farm just south of the Borden County line in northern Howard County is expected to be connected to the grid in the first quarter of 2024.

HighPeak primarily is targeting the Lower Spraberry and Wolfcamp A formations at about 6,500 feet in depth, which is shallower than the same formations in the central Midland Basin. That is yet another advantage because it reduces drilling and lifting costs.

Hollis says the 37,000 boe/d in the first quarter came from about 185 producing wells. The company has drilled 250 wells, however, meaning another 60 or so wells are somewhere in the process of being completed. HighPeak has operated as many as six rigs and four frac crews over the past year. Hollis says it is dropping to two rigs but is keeping two frac crews to allow it to complete some of its drilled but uncompleted inventory. The two rigs and two frac crews for the rest of this year will allow the company to continue completing at a four-rig cadence, according Hollis.

“We plan to pick up two additional rigs in 2024, assuming commodity prices warrant,” he reports.

Hollis notes that also will allow the company to have free cash flow by the third quarter of this year while still maintaining significant growth. HighPeak is drilling four or five wells per pad with average lateral lengths of 12,000 feet.

Horseshoe Laterals

Companies in the Permian continue find creative ways to increase production and lower costs. One of the more innovative developments is Matador Resources’ pilot project using a “horseshoe” design in Loving County.

Glenn Stetson, executive vice president, says Matador has drilled a two-mile lateral on a section only large enough for a traditional one-mile lateral. The U-shaped lateral drills out part of the wellbore, makes a 180-degree turn and then drills back toward the rig to double the lateral length.

Matador Resources is piloting a “horseshoe” lateral design in the Delaware Basin. The well architecture has a U-shaped lateral that drills out one mile before making a 180-degree turn to drill back toward the rig. The design effectively doubles the length of a one-mile lateral.

“Our operations team has always worked closely with our geophysical and land teams to find new and innovative ways to reduce costs and increase production and returns from our existing acreage,” Joseph W. Foran, chairman and chief executive officer of Matador, says in his first-quarter shareholders’ letter. “We are now testing our first batch of horseshoe wells in our Wolf asset area in West Texas, which we expect to allow us to drill two-mile lateral wells in one-mile land-locked sections.

“By successfully drilling U-shaped laterals, we should be able to increase our inventory of two-mile locations across our Delaware Basin assets and continue to expand capital efficiencies by accessing longer laterals in sections previously limited to one-mile wells. We estimate approximately $10 million in cost savings will be realized by drilling two U-shaped two-mile wells compared to four one-mile lateral wells in this section,” Foran stated.

Matador also announced that it had closed its acquisition of Advance Energy Partners Holdings on April 12 for approximately $1.6 billion that added over 100 million barrels of oil and natural gas reserves to the company’s 357 MMboe of oil and natural gas reserves. According to Foran, the acquisition added 18,500 net acres in the core of the northern Delaware Basin, most of which is adjacent to the company’s best acreage.

Matador Resources now has 150,000 net acres in the Delaware Basin. Average production was 106,644 boe/d (58,941 bbl/d of oil), according to the company’s first-quarter earnings report.

Northwest Shelf

Houston-based PEDEVCO Corp. is targeting the San Andres formation on the Northwest Shelf in a remote area of Chaves and Roosevelt counties in New Mexico.

“This area had 40-acre-spaced vertical wells drilled in the 1950’s and ‘60s,” explains PEDEVCO President, J. Douglas Schick. “Most of the San Andres in the Permian Basin, especially on the Central Basin Platform, was drilled on 5-10-acre spacing. So, what we are doing is down spacing with 20-acre spaced horizontal wells.”

On the Northwest Shelf in Chaves and Roosevelt counties in New Mexico, PEDEVCO Corp. is drilling horizontal wells on 20-acre spacing into the San Andres formation. Given the San Andres formation’s relatively shallow depth of 4,500 feet, the wells are designed with one-mile laterals.

The San Andres formation is relatively shallow at about 4,500 feet, and PEDEVCO is drilling one-mile laterals. “It is not deep enough to push more than 1.25 miles,” he relates.

PEDEVCO has 31,000 acres over three fields on the Northwest Shelf: Chaveroo, Chaveroo Northeast and the Milnesand field. It has 14 total horizontal San Andres wells and has drilled 10 horizontal San Andres wells in Chaveroo and one in Chaveroo NE to date. It acquired three horizontal San Andres wells in Chaveroo NE in 2019. The company’s focus, however, is strictly on its Chaveroo acreage at the moment, although Schick says drilling there is currently on hold while it is using $16 million in capital expenditures to drill or participate in the drilling of 14 wells in the Denver-Julesburg Basin in Colorado and has another 11 wells it plans to drill or participate in later this year in the D-J Basin.

“We also have permits for three more wells in the Chaveroo Field that we can drill any time,” he adds.

While a number of companies are targeting the San Andres on the Central Basin Platform in Andrews County, Schick claims PEDEVCO is the only one doing horizontal drilling in the legacy San Andres fields on the Northwest Shelf.

“We are using a cross-linked gel frac,” he offers. “It is not a real big frac at about 500-700 pounds per foot. When we open a new wellbore, we are just trying to stimulate everything in the near wellbore main pay zone and stay away from the lower zones because the San Andres can produce a lot of water.”

Schick says the average well has 300,000-350,000 barrels of estimated ultimate oil recovery.

“But the 30-day initial production rates can be volatile,” he continues. “We had one well with an IP of 500 bbl/d and a 30-day IP of 450 bbl/d. On average, these wells peak at 250-400 bbl/d for 30 days. They flatten out after a year. They decline ~92% in the first year and about 8% percent per year after that, with all of our wells producing around 40 bbl/d after a few years.”

Managing water is one of the biggest challenges in drilling these San Andres wells, according to Schick. When the wells first come on line, he says they use electric submersible pumps.

“These wells produce ~90% water, so when they drop to 500 bbl/d of total fluid, we put them on rod pumps, which are cheaper to operate,” he explains. “It usually takes about two years to switch to rod pumps.”

Schick points out that the San Andres wells produce 90%-93% oil and only “a few hundred Mcf/d of gas,” which is normally sold to Targa.

“We have to flare what is not sold to Targa because the gas contains hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide,” he states. “It is very minor, but over the next five years, we plan to put in facilities to clean up the gas.”

Schick says PEDEVCO has more than 100 potential drilling locations in the Chaveroo Field alone.

Storm Clouds

While the Permian continues to enjoy record-setting production numbers, Kirk Edwards expresses concern about storm clouds on the horizon. “There has been a lot of inflation in drilling and service costs over the past year, even though supply chain problems have become less severe,” says Edwards, who is president and chief executive officer of Latigo Petroleum LLC in Odessa.

While oil prices have been hovering in the $70/bbl range, most Permian wells also produce associated gas.

“That is especially difficult now because natural gas prices are near zero when you factor in compression and transportation costs,” he adds. “WAHA hub prices are about 50% of NYMEX right now.”

Although Edwards lives in Odessa, Tx., in the heart of the Permian Basin, Latigo’s operations are in the Texas Panhandle. But he says conditions are the same for both areas.

“This has caused some small independents such as myself to pause,” he states. “We have drilled 14 wells over the past year, but we have laid one rig down to see if drilling and service costs come down.”

Edwards, a past president of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, notes that the number of oil and gas rigs operating in the fourth week of May had dropped by 15 to 696 nationwide, the lowest total since April 2022. With more than half of those rigs operating in the Permian, he contends that will mean Permian production may plateau with another 200,000-300,000 bbl in the future.

“With rigs coming off the market now for five consecutive weeks, I think we will see less hectic activity levels and an impact on oil production,” he adds.

They are plenty of other questions on the horizon, too, such as a predicted recession, what the government plans to do about replenishing the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the situation in Ukraine, and China’s comeback in manufacturing, to name only a few.

“The bigger independents will stay the course,” Edwards predicts. “They don’t necessarily react to higher or lower oil prices. They have a different model than everyone else. The question is what do the smaller independents do? Do they continue or will they pause? That is especially true in the Permian, which is so investment intensive.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.