Horizontal Drilling Accelerates In Permian Basin

By Colter Cookson

The U.S. industry’s quest for liquids-rich plays is leading operators to double-down on the prolific Permian Basin, the long-standing cornerstone of domestic oil supply. And with an abundance of conventional and unconventional plays to choose from, the question for operators in the Permian these days is which formations to target to get the highest rate of return.

From the Spraberry to the Wolfcamp, the Cline, and even the Atoka, Permian Basin operators have all kinds of oil and liquids-rich targets to drill. The challenge is figuring out which to pursue first, and how to get the most from each well.

In much of the basin, the answer involves switching from vertical to horizontal wells. While this increases the amount of capital required to drill each well, it boosts production rates and estimated ultimate recoveries enough to turn already worthwhile vertical opportunities into horizontal capital magnets.

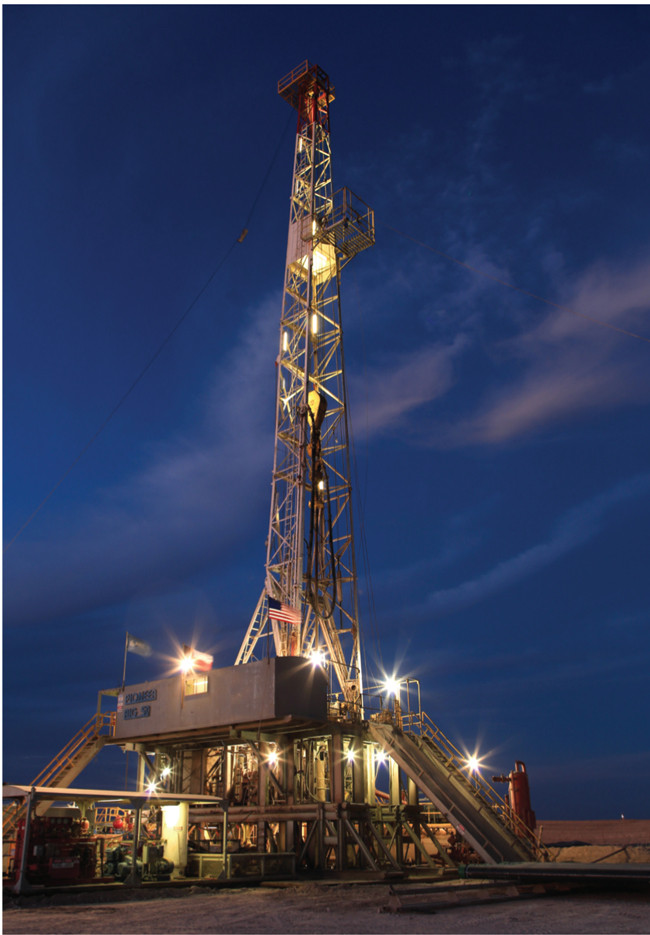

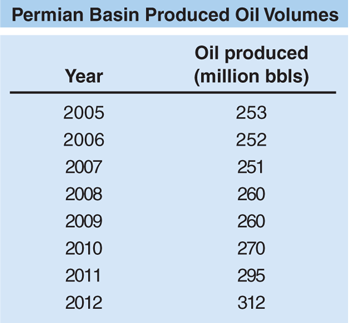

As of mid-May, there were 455 rigs active in the Permian Basin, nearly double the average rig count in 2010. Drilling permits were up for a third consecutive year in 2012, with 65 percent more permits issued than during the U.S. drilling “peak” of 2008. The end result, according to the Texas Railroad Commission, is that Permian oil production has soared from 260 million barrels in 2009 to 312 million barrels in 2012. After first halting a long, steady decline in oil output, operators have turned the historical trend line on its head, increasing total oil volumes by an average 17.3 million barrels in each of the past three years!

As producers extend promising plays and optimize drilling and completion techniques, the rig count is expected to maintain its upward trajectory. The companies behind this climbing activity are independents with names such as Laredo Petroleum Holdings Inc., HighMount Exploration & Production LLC, Reliance Energy Inc. and Strand Energy LLC. Many of them are home-grown companies that continue to do what they have always done: find new reserves in a liquids-rich sedimentary basin that has redefined the term “oil boom” time and again, but this time has added new horizons of resource plays to the list of drilling opportunities.

“The Permian Basin is going to be one of the best, if not the best, oil shale plays in the world,” predicts Randy A. Foutch, Laredo’s chairman and chief executive officer. “The quality of the basin keeps getting better and better as we gather more data.”

To illustrate, Foutch uses Laredo’s Garden City project, which includes 142,600 net acres in West Texas’ Glasscock, Reagan, Howard and Sterling counties. “The vertical wells in this area give us repeatable rates of return in the high teens or low 20s,” he reports. “I have spent most of my career looking for programs with those kinds of returns, but today, I am trying to minimize our vertical drilling because our horizontals provide even greater returns.”

The company has confirmed four horizontal targets on its Garden City acreage: the Upper Wolfcamp, the Middle Wolfcamp, the Lower Wolfcamp and the Cline. Foutch says the four Upper Wolfcamp wells it drilled in the first quarter, which had 7,200-7,500 foot laterals and were completed using 27-28 stages, had initial production rates averaging 880 barrels a day, with the best producing 1,160 bbl/d. The company also drilled wells targeting the Lower Wolfcamp and Cline that delivered comparable production, he adds.

As of early May, Laredo had drilled 68 horizontals into the Wolfcamp and Cline, Foutch notes. Through these wells, he says the company has derisked 80,000 acres in the Upper and Middle Wolfcamp, 73,000 acres in the Lower Wolfcamp, and 127,000 acres in the Cline.

“We have a 20-year inventory of drilling opportunities,” Foutch relates. “We are trying to figure out the best ways to accelerate that drilling to a shorter time frame that provides maximum net present value.”

To gain more capital for its Permian Basin drilling program, Laredo has agreed to sell its Granite Wash assets, which include 104,000 net acres, to affiliates of EnerVest Ltd. for $438 million. “We always have liked the Anadarko Basin, but our Garden City acreage has a much better rate of return, so we believe it will be the best place to put our capital,” Foutch comments.

Development Drilling

The asset sale will enable Laredo to increase its Permian Basin rig count from four to six, Foutch reports. “While we are spending some capital derisking additional acreage, we are focusing on development drilling,” he says.

With four proven horizontal intervals, Laredo Petroleum has decades of drilling opportunities available on its Garden City acreage. The intervals deliver such great returns that the company is divesting its Granite Wash acreage to put more capital into the Permian Basin.

As part of a broader effort to develop best practices in its Garden City operations, Laredo will drill multiple horizontal wells off a single pad, with each well targeting a different interval. “We are stimulating these wells and getting microseismic and other data to test our frac designs and confirm that we have enough space between the laterals,” Foutch says. “We also are drilling side-by-side wells 660 feet apart and capturing similar data to make sure that is the correct spacing for us to use as we develop the field.”

The data also will help the company improve its hydraulic fracturing designs, Foutch adds. “We have drilled 80 horizontal wells in the Permian, so we already have optimized our designs significantly. However, we are still experimenting to determine the right amounts of sand and water to pump, and the optimal injection rates and pressures,” he details.

In the long run, Foutch says Laredo hopes to find a way to determine ahead of time which parts of the horizontal will yield the most production so it can focus its proppant and water injections on the best ones. “We want to put our money where it will do the most good,” he explains.

The company also is looking for ways to use nonpotable water in its frac jobs and reclaim frac flow back. “We are early in that process, but we know we can reclaim and reuse some of the flow-back water,” Foutch reports.

In addition to developing its the Wolfberry and Cline intervals, Laredo plans to gradually test horizontals in other intervals, such as the Spraberry. “In some places, the Spraberry lends itself well to horizontal drilling,” Foutch observes. “We think it has the potential to do so on parts of our acreage. Some of the zones below the Cline, particularly the Strawn, but also the Atoka, have tremendous potential.”

The company also is drilling on its China Grove project, which consists of 58,000 net acres located primarily in Mitchell County, Tx. “Based on whole and side wall cores from two vertical wells, we believe this area will have similar reservoir properties to the Garden City acreage,” Foutch says. “We have completed our first horizontal test, but we need more data to determine whether the area will be able to compete for capital with the Garden City acreage. If it can pass that high bar, it will be a great asset.”

Transition

Like many operators, HighMount Exploration & Production is looking for ways to increase its oil production. “Our core asset is the Sonora Field in the Permian Basin, which has been a gas field for most of its history, with 70 percent gas and 30 percent liquids,” notes Steve Hinchman, the company’s president and CEO. “We are trying to transition to a more balanced portfolio, not only in terms of commodities, but also in terms of the basins in which we participate.”

Although HighMount has 70,000 net acres and an active drilling program in the Mississippian Lime, as well as growing Granite Wash acreage, Hinchman says its legacy assets in the Permian Basin will play a key role in its efforts to diversify. “The Wolfcamp Shale is a game-changing opportunity for HighMount,” he remarks.

The company has 600,000 acres in the southeastern portion of the Permian Basin, most of which are held by production. Hinchman indicates that 150,000 of those have high Wolfcamp potential. “In some places, we may have the ability to stack four horizontal targets,” he says. “That would give us 200 million barrels of oil in place potential for every one square mile, which is massive. In fact, it is two to three times the oil in place in great plays such as the Eagle Ford and Bakken shales.”

To test the Wolfcamp on its acreage and identify the best locations for horizontal wells, HighMount drilled or recompleted 40 vertical wells in 2011, Hinchman relates. Then last year, it used that information to drill 13 horizontal wells, most of which targeted the “B” interval in the Upper Wolfcamp formation. “Each well was better than the one before it,” Hinchman reports.

For the first half of 2013, HighMount has taken a break from its horizontal drilling program to collect additional information from vertical wells and to analyze the data from a newly acquired 3-D seismic program. “We likely will bring at least one horizontal rig and maybe two by the end of this year,” Hinchman says. “Those rigs will continue to delineate the Wolfcamp B, using next-generation well and stimulations designs.”

Hinchman adds that the rigs will test the Wolfcamp A and C zones as well. “We have a small sample of horizontal tests in both zones that suggest they may be better than the B, so we are looking forward to building our understanding of those intervals,” he comments.

Lessons Learned

Since its Wolfcamp program started, HighMount has come a long way, Hinchman reports. “Our initial wells cost more than $7 million apiece, but we have gotten the costs down to $5 million, which is better than most of the operators in the basin,” he says.

HighMount Exploration & Production is drawing on data from vertical test wells, a 13-well horizontal Wolfcamp program, and 3-D seismic to develop next-generation well and stimulation designs. By placing its laterals more precisely and completing wells more efficiently, the company hopes to improve the already impressive economics of its Wolfcamp acreage.

Early production results improve with each well and reasonably match those of other operators’ Wolfcamp wells, Hinchman continues. “Because we use gas lift rather than electrical submersible pumps, our initial production rates are lower,” he allows. “However, our initial decline rates also are lower.”

HighMount decided to use gas lift for several reasons. “Our wells can be gassy and produce quite a bit of sand, so we believe gas lift will create a more stable drawdown early on. In the long run, we will spend less time fixing pumps. Also, because we have gas infrastructure nearby, gas lift is less expensive to operate,” Hinchman details.

The company hopes to get even better production from its next set of wells by using the data it has collected so far to more precisely place laterals, Hinchman says. “In our early horizontals, we put our wells where everybody else was,” he notes. “As we have collected data and looked at where our better wells have been, we have realized there are adjustments we can make to optimize the horizontal’s placement and improve the efficiency of our stimulation to connect the well bore to more oil volume.”

Hinchman suggests that even small changes in where a lateral lands can be significant. “We went into our drilling program thinking we could target ±50 feet,” he says. “Today, we want to target our wells at ±five feet.”

To optimize its frac designs, HighMount is using production tracers, detailed petrophysical and 3-D stress data, and fracture simulation tools. Hinchman says this work has revealed “stress shadowing” that suggests the perforation clusters were spaced too close together. The stress shadow effect occurs when hydraulic fractures are in close enough proximity that induced fractures are influenced by the stress fields of nearby fractures, creating higher net pressures, smaller fracture widths, and changes in the associated complexity of the stimulation, he explains. “It looks like the stress fields are preventing the adjacent stages from stimulating the rock, so we will be moving our perforation clusters farther apart,” he says.

Hinchman says HighMount, and the industry as a whole, will be able to complete wells more efficiently by focusing its frac jobs on the most productive intervals. “As we get better at understanding the primary drive mechanisms within these plays and identifying which rock will contribute, we will be able to pinpoint fractures more specifically,” he predicts. “This will allow us to drive down costs while improving ultimate recoveries.”

Optimizing Gas Wells

In addition to testing and drilling the Wolfcamp, HighMount is finding ways to increase production from its legacy wells in the Sonora Field, Hinchman reports. “Automation has played a key role in that effort,” he says. “The field is hooked up to supervisory control and data acquisition systems, so we can monitor and operate wells remotely. Of our nearly 6,000 producing wells, half are pumped by exception. In other words, the automation system continuously monitors the well and alerts us of potential problems so we can address them.”

HighMount decided to pump those wells by exception primarily to reduce the costs associated with contractors and overtime, Hinchman says. Initially, the company thought operating by exception would cause its production to fall. “Instead, we have seen it increase,” he says. “Reducing costs has transformed from being the primary goal to being the cherry on top of greater production.”

Automation also has increased efficiency by allowing the company’s staff to focus their time and attention on problematic wells, Hinchman says. “Our staff no longer need to travel to every well and can look at a given well several times a day, so they can provide more engineering support,” he adds.

At its employees’ suggestion, Hinchman says HighMount has formed an internal group of plunger lift experts that will monitor the pumps and look for ways to optimize them. “By using the information we are getting through telemetry and controlling the plunger remotely, we believe this group of employees will be able to increase production without any additional capital expenditure,” he predicts.

Vertical Driller

Reliance Energy is one of many Permian Basin producers that is investing most of its capital to drill vertical Wolfberry wells completed with multistage hydraulic fracturing in multiple zones. “Of the five rigs we have running, four are dedicated to vertical wells and one is dedicated to horizontal wells,” notes Denzil West, the company’s vice president of asset development.

After a long period of incrementally declining crude oil production in the Permian Basin, operators have reversed the trend line, growing annual oil output by 52 million barrels between 2009 and 2012, representing a 20 percent increase. With an abundance of conventional and unconventional resource plays to target, oil drilling activity across the basin continues at the highest levels experienced in decades. SOURCE: Texas Railroad Commission production data query (March 2013)

Reliance’s vertical drilling program is focused on 60,000 acres in Martin, Andrews and Ector counties. “In most of our wells, we complete the Atoka, Strawn, Cline, Wolfcamp, Dean, Spraberry, and Clearfork,” he notes. “The wells typically cost $2 million to drill with an average depth of 11,800 feet.”

In general, West says the wells initially produce more than 100 barrels of oil and 400 Mcf of gas a day, and have estimated ultimate recoveries averaging 215,000 barrels of oil equivalent, with 85 percent of the production liquids and oil. “They usually have a steep decline at first, but taper off quickly to a terminal decline rate of 5-6 percent a year,” he adds.

Since it first started drilling vertical Wolfberry wells in 2007, Reliance has cut its drilling time from 14 to 10 days, West says. “We preset our surface casing to save rig time,” he notes. “We also use top drives on all the rigs and generally use downhole motors. The motors add to daily costs, but if you run them correctly, they are worth the money.”

Reliance completes most of its Wolfberry verticals in 12-13 stages placed in multiple formations/zones intersected by the vertical well bore, West reports. “We are constantly evaluating our completion schemes within individual stages to refine the best practice,” he says. “For example, we have been experimenting with high-rate slick water frac techniques in certain zones to increase productivity and recovery.”

West says it is too early to tell whether that technique will be beneficial in the long run. “It is made some difference early on, but we have been doing it only for the past 10 months, so we do not know whether it will be better in the long term,” he remarks.

In addition, Reliance has led horizontal efforts in the basin by drilling laterals in the Atoka, and will be one of the first operators to drill horizontal Cline wells in the western part of the Midland Basin, West notes. “Our Atoka wells have been very, very productive,” he says.

On an additional 45,000 acres in the southern part of the basin, West says Reliance plans to drill exploratory wells targeting the Strawn, Wolfcamp and Clearfork horizons.

Cline Driller

Strand Energy has been generating prospects and drilling in the Permian Basin for 25 years. “Today, we are active in the western part of Sterling County, where we have 20,000 acres,” says Kent Brock, president and manager.

The company’s main target is the Cline, Brock notes. “The formation is relatively thick at 260-300 feet, and there is Cline activity on all four sides of our lease block,” he observes.

In mid-May, the company was drilling its first two Cline horizontals. “These wells should reach a vertical depth of 8,200 feet and will have horizontals that are one and a half sections long,” Brock says. “They are on the same pad, but we are using different completion techniques, so we can compare the results to see which approach works best.”

Brock says the company plans to drill a third Cline horizontal later this year. “If the results are good, we plan to continue development next year,” he says.

Strand is participating in a 3-D seismic shoot on its acreage, Brock says. “The survey should help us optimize the Cline and gain more information about the Fusselman and Ellenberger underneath the Cline for future vertical wells,” he explains.

On acreage in the northwestern part of Gaines County, Strand is drilling development wells that target the Lower Clearfork. “In our area, the Lower Clearfork generally has been stimulated with a large acid job,” Brock notes. “We went into it two years ago thinking we could accelerate the production using hydraulic frac jobs instead of acidizing. We have seen higher front-end production on our new wells than the old ones, so that appears to be working.”

The company completes its Clearfork wells by pumping 100,000-140,000 pounds of 20/40-mesh white sand down hole in a cross-linked gel, Brock details. He says the wells have an average depth of 7,800 feet and cost $1 million to drill and complete.

“We are seeing average first 30-day production rates of 80 bbl/d and estimated ultimate recoveries between 75,000 and 100,000 barrels,” he reports. “In general, the wells give us three-to-one or four-to-one returns and reasonably quick payouts.”

Strand also has acreage in the east-central part of Irion County that it has been developing for the past three or four years. “We are drilling vertical wells that commingle the Canyon Sands, Wolfcamp Lime and Lower Clearfork Lime zones,” Brock says.

The wells have vertical depths around 6,500 feet, Brock notes. “They are not as consistent as the wells we are drilling in the Lower Clearfork in Gaines County, but because we comingle the various zones, the average well is ok,” he says. “Already having production facilities and other infrastructure in place makes it easy to continue developing the acreage.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.