International Hot Spots

Independents Positioned To Achieve New Successes In International Operations

By Mike Lakin

LONDON–Unconventional oil and gas development obviously has been a game changer for most U.S. independents over the past decade. But while shale gas and tight oil plays have completely transformed domestic markets, despite some early impact on potential international play areas (particularly Australia and parts of Northwest Europe), unconventional resource development remains in its infancy outside North America.

The level of global participation in international projects by mid- and large-cap U.S. independents, which helped pioneer exploration projects in the Middle East, Central Europe, North Africa, South America and elsewhere in the 1970s and ’80s, has diminished dramatically in recent years. Only a small number of U.S. companies have been active in the international arena since the early 2000s, focusing instead on home-grown success, building both onshore lower-48 conventional and unconventional portfolios.

The level of their achievement has been stunning. However, with unconventional activity increasingly shifting to more of a development/exploitation phase and low potential for large new conventional plays in the United States, international exploration opportunities–both conventional and now unconventional–are looking more appealing to some American firms. Economic rewards large enough to propel a company higher by orders of magnitude appear likely to again attract proportionally greater numbers of U.S independents to global operations.

That is not to suggest that U.S. companies are not already active internationally. On the contrary, a number of domestic oil and gas companies of all sizes continue to be very successful in global projects. A cursory glance at the coastline of Africa, for example, ably demonstrates this fact. Offshore Ghana, the Jubilee oil discovery by Tullow Oil, Kosmos, Anadarko Petroleum and Sabre Oil & Gas has drawn the rest of the world quickly into the prolific new West African deepwater Transform Margin (Cretaceous) play.

Farther south, offshore Gabon, Houston-based Harvest Natural Resources’ oil discovery in a complex Atlantic presalt play that is being unlocked by 3-D seismic, north of the largest sub-Saharan oil production in Angola, shows that diligent application of advanced technology (particularly seismic imaging and processing) in a previously explored area can lead to major new discoveries.

Across the continent, Anadarko’s multiple large gas discoveries along the relatively unexplored East African coast have triggered a surge in interest both offshore and onshore Mozambique and Tanzania after being largely dismissed in the past as too gas prone and unlikely to be profitable. Since 2010, Anadarko and its partners have drilled more than 20 deepwater wells in the Offshore Area 1 Block, discovering an estimated 45 trillion-70 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas. First cargoes from an onshore liquefied natural gas facility are scheduled to ship in 2018, with Mozambique expected to eventually become one of the world’s three largest LNG exporters!

International projects will have to continue to compete head-to-head with domestic resource play investment opportunities for U.S. independents, but as these world-class project successes illustrate, there is no shortage of high-impact opportunities available to independents seeking to venture overseas.

Getting A Toehold

Where will companies look to find the next frontier to maintain their growth and investment returns while diversifying portfolios heavily weighted toward onshore U.S. resource plays? How can they get a toehold on the global stage while staying one step ahead of the competition? The good news is that the hard-earned technological expertise (both conventional and unconventional) and capital of U.S. companies is in top demand around the globe.

Interestingly, where conventional exploration is well established, experts say that even many of the world’s most mature hydrocarbon basins have not produced more than 3-5 percent of their estimated in-place resources. And, of course, the world’s huge unconventional potential has barely been scratched outside of North America. Unconventional resources have become a key focus in Northwest Europe (particularly Poland) and Australia, although fracturing restrictions have limited exploitation in some areas (including France and parts of Australia).

In contrast, the U.K. government has passed laws to positively encourage unconventional development, realizing that its potential may help relieve the country’s dependence on European gas supplies it does not control. Only time will tell if the geology is suitable for commercial exploitation, although established infrastructure, ready markets and generally high gas prices (U.S. $8-$13/Mcf) significantly help the economics. If success leads to growth in the necessary service sector (which is limited) and associated economy of scale, it would improve the economics further.

But, who is looking at unconventional reservoirs in North Africa, parts of the Commonwealth of Independent States and Asia, to name several possible areas with potentially large unconventional resource potential? Ever-increasing energy demand undoubtedly will encourage the growth of infrastructure in these unconventional frontiers, which will help to stimulate local gas markets to ensure that significant discoveries can be commercialized in most parts of the world in time.

The North American Prospect Expo held in February in Houston offered evidence of a renewed international focus by some American companies. The specific skill sets that U.S. companies have developed at home can be leveraged to unlock the potential of international plays in areas bypassed by a lack of sufficient local financial resources and available expertise.

For any explorer, success is all about finding commercial quantities of hydrocarbons at minimum expense and making money from its exploitation. But the realities of the global market make that more difficult and more costly than it used to be, and in many cases, more expensive than in North America.

Those realities include maintaining production in depleting mature fields around the world; rising capital expenditures needed to explore more remote and challenging frontiers, including ever-deeper water; developing a global liquefied natural gas supply chain to commercialize new gas reserves; and the engineering resources needed to exploit unconventional resources outside North America. These factors certainly make international operations as challenging as ever, especially given the state of global geopolitics and economics.

Formula For Success

There is no doubt that the phenomenal expertise, technological advances and capital generated domestically during the past decade will be invaluable to any U.S. company seeking to expand internationally in underexplored basins and plays. However, knowledge and operational know-how are only part of the formula. Operators also must have a clear understanding of the “processes,” “cultures” and associated “additional time” that are essential to establishing, growing and managing international operations.

Success also requires experienced international personnel, the time to allow an international plan to work, and of course, the right types of projects. A limited number of experienced geologists, geophysicists, engineers and other technical personnel is already one of the main challenges to any company exploring internationally, but it is arguably the single biggest challenge for U.S. operators. American companies in all sectors of the upstream industry understand all too well the shortage of trained geotechnical and engineering personnel that will be needed in the future as a large percentage of the existing workforce retires. As a result, older employees in United States with experience in overseas projects are an invaluable resource to companies considering going international.

Managing time expectations is critical. Investors that want a “quick return” will all too often encourage companies to achieve what is simply not possible within the one- to three-year time frames that financial markets typically desire. Many international projects need at least three years, and often five or more, to develop from an initial ground floor license application.

The alternative is farming into deals whose owners have near-term obligations, but selecting the right farm-in project that fulfils a company’s criteria is an equally time-consuming process. Although there are always numerous farm-out opportunities available in all regions of the world, interested companies have to do their homework to find the select few that properly “fit” their project search criteria. In fact, international players commonly look at 100+ international deals before finding one that fits their own company’s specific criteria.

Going International

There are essentially three main ways of participating in international deals:

- Secure a ground floor application for acreage from host governments and national oil companies. This approach requires very long lead times and establishing exploration teams in order to work them properly, either as a group of companies or for potential farm-out before seismic acquisition and/or drilling.

- Farm in to an existing project. The benefits are much shorter lead times and the opportunity to join an established partner with local knowledge and relevant experience. The incoming company usually will be expected to carry its partner’s interest through a defined work program. Typical deals involve a two-to-one carry, with the most prospective deals in competitive and sought-after areas going on a three-to-one basis. The key benefit is that the best deals can be cherry picked, if the right search and review process is established.

- Another means of participating in new international deals is through a corporate deal with an established player, but this is rarely easy to achieve unless done as a leveraged merger or back-in with a company bringing material funding and/or expertise.

The effort to find the right opportunity begins with having a clear set of technical and commercial criteria for the type of deal desired, and the insight, flexibility and review process in place to uncover deals that match the criteria. This sounds simple enough, but finding the right deal requires experience, patience, time, capital and the right plan, plus an appreciation and respect for working in a different country, along with a little luck to put one’s self in the right place at the right time.

Most of the significant international successes by independents over the past 20 years have been in frontier areas where the companies were willing to take measured exploration risk, and in some cases, political risk, and not necessarily in areas where others have been willing to operate. These companies have not followed others, but have led by their own conviction, knowledge and detailed technical work, understanding of local culture and politics, and by employing clear and fast decision making. They have also had exploration failures, but structuring their international plans so they have a “conveyor belt” of deals they can afford and/or farm out with enough time to meet the work requirements gives them a chance to succeed.

Whether pursuing conventional or unconventional resources, entering a new country can be daunting. Questions such as where in the world to go, what basins and plays to target, and how to deal with regional politics can be overwhelming. The starting point depends on a company’s initial criteria (i.e. exploration and development or production, onshore or offshore, shallow or deep water, gas or oil, frontier or proven producing region, willingness for low or high political risk, the size and availability of international budget, the timeline for success, rate of return, etc.).

Hot Spots

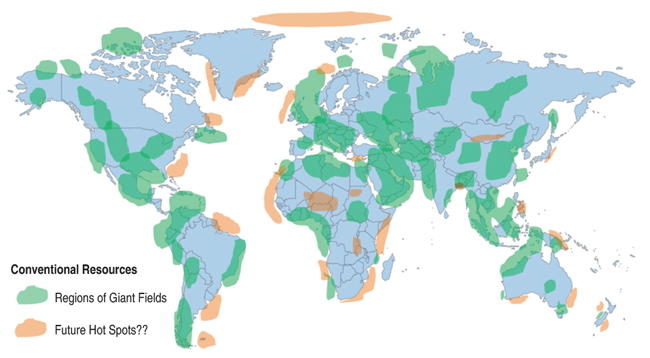

The schematic in Figure 1 shows proven hydrocarbon areas of the world along with possible new frontier hot spots that are either the focus of ongoing international activity or likely to be in the future.

One could write an encyclopedia about where to look for specific types of deals to fit specific search criteria. Needless to say, most of the proven/producing areas that are deemed politically safe with accessible markets and stable fiscal regimes are highly competitive areas with the best acreage already held by established companies. These include most of the proven basins in the stable parts of West, Central and East Africa; Northwest, Central and Eastern Europe; Australasia; New Zealand; Asia and the Far East; and South America.

However, many areas of the world remain prospective and not yet proven by drilling because of their remoteness, challenging environments, political changes and unrest, or limited by wars. The latter also can affect previously stable areas, as has been the case in North Africa over the past three years and historically in several countries in South America, where regime changes have led to nationalization and the exit of established players.

That said, history shows that if a pioneering company discovers significant potential in a frontier area, or overcomes perceived political difficulties, such areas can quickly become new hot spot and attract others willing to overcome the challenges and adversities. In politically sensitive regions, the risks are more often than not in the eye of the beholder.

Source of Opportunity

Publications, media, industry association literature, the Internet, and specialist acquisition and divestiture agents are all obvious places to start the search for international deals. But once a defined search area of appropriate opportunities has been identified, it is crucial to travel to meet the key operators of the acreage, wherever they are based. More often than not, that is in the key Western cities, and not in the country in which the acreage of interest is located. At the appropriate point, the search process should also involve travel to the countries of interest in order to meet the people on the ground, get a lay of the land, and importantly, absorb some of the local culture and understand the different ways things are done.

This should initially involve identifying people with local experience and knowledge who could be of assistance. Local agents and lots of air miles and shoe leather to establish a contact database and develop regional relationships are a must! Such investment of time undoubtedly will reward the early efforts significantly, if and when a commitment of serious resources is made to a project.

Attending the right international conferences also can be very helpful. Examples of international acquisition and divesture events are the annual American Association of Petroleum Geologists’ Prospect and Property Expo held in March in London, and NAPE held each February in Houston. Regional events include the Petroleum Exploration Society of Great Britain’s PROSPEX fair held each December in London for mostly North European (including North Sea) deals, South East Asia Petroleum Exploration Society’s SEAPEX conference held biannually in Singapore for Southeast Asian deals, and the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association’s annual APPEA conference held in April or May in Perth for Australasian deals.

Publically available international deal statistics from U.K.-based consultancy JSI Limited shows that it takes an average of 12+ months for international deals to be farmed out, so even when an appropriate project is located, it takes time to review and close a participation deal. The average success rate of the international exploration projects screened over the past 14 years and deemed to have discovered commercial hydrocarbons is about 20 percent, which highlights the need to manage portfolio interests to balance budgets and increase the chance of success by mitigating often large expenses and higher technical risks.

Equally interesting, the statistics show that the success rate on recent exploration wells drilled in the U.K. sector of the North Sea (a very mature hydrocarbon area) after farm-outs to companies that were not considered established players have averaged 10 percent, which compares with a 30 percent success rate for deals farmed out to established companies. Perhaps it would be a good idea for a new entrant to an area to work with established and experienced players?

However, this outcome is probably no different than participating in North American exploration projects, other than the higher costs, different cultures and longer lead times involved in international projects (keep in mind that these factors often are matched by significantly higher individual asset values, if successful).

Buyer’s Market

Established international players recognize that the international A&D arena is currently a buyer’s market. There are plenty of upstream deals available that are constrained mostly by the availability of the capital required to fund them. The few integrated upstream players with production revenues are mostly at their budget capacities, and capital markets have been slow to respond, following the financial crisis of 2008-09. Entry costs are often favorable and local competition is limited in many regions as a result. New money from private equity, national oil companies and sovereign wealth funds have had the pick of deals over the past five years.

Cheap production deals are generally scarce because of high commodity prices around the globe, but demand remains high as many smaller companies and new entrants look to create cash flow “footprints” to establish operations and attract capital from financial markets.

However, there are many smaller companies with good exploration deals that they are not able to fully fund to meet project work commitments, and good farm-in terms are available on many of these projects. Successful North American companies with money, technical expertise and technology are potentially a perfect match for joint ventures with experienced, albeit cash-strapped, players in the global market.

Take, for example, the West African Transform Margin, where the giant Jubilee discovery defined the new deepwater Cretaceous (Turonian) play in the Tano Basin offshore Ghana in 2004. That discovery led to a 14-well exploration drilling spree looking for other Turonian play analogues at a combined cost of more than $1 billion, with none so far announced as commercial. Not surprisingly, the appetite to farm in by others to drill promoted wells is no longer what is once was. One might argue that since most of the Turonian analogues drilled reportedly have found significant shows, there is an active hydrocarbon system and now is the time to revisit the projects that have not been drilled with a different mindset to see if there are different Cretaceous plays (including the Campanian) that may be equally unique reservoirs like the Tano Basin elsewhere on the transform margin trend.

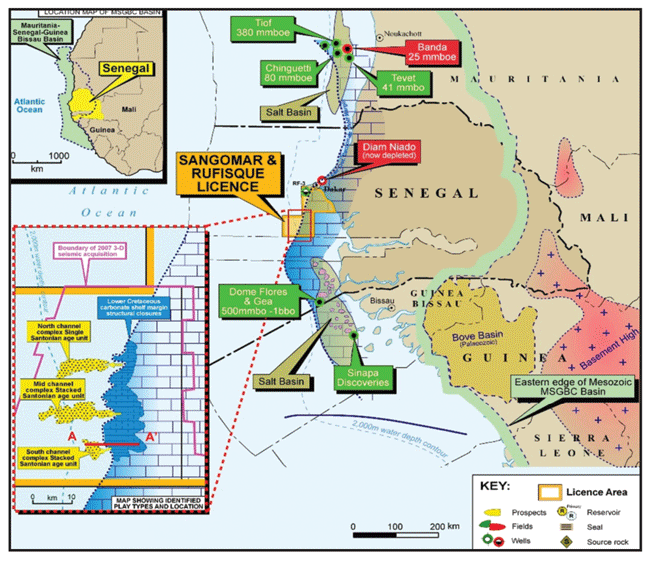

A recent farm-out deal in deepwater Senegal (Figure 2) took more than three years to attract the right companies willing to commit to drilling. Progressive marketing efforts saw a transition of interested parties, with initial interest shown by companies that were unable to commit the funds needed for deepwater drilling because of their size and lack of capital backing at the time. Although the technical work continued over the three-year marketing period, rather than a material change in the hydrocarbon potential or risk profile, it was more a matter of the industry’s changing perception of the potential of deepwater acreage offshore Senegal that ultimately led to commitments from Cairn and ConocoPhillips for a $190 million, two-well drilling program due to start imminently.

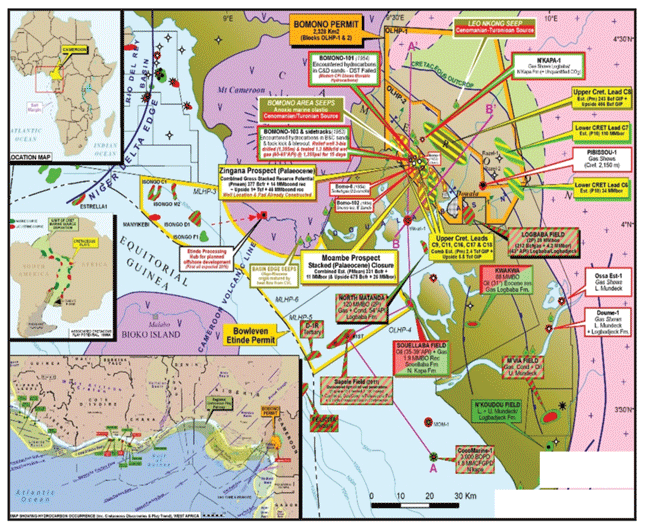

An example of a project with smaller capital requirements looking for new international partners is a deal onshore Cameroon (Figure 3). The project on offer by Bowleven PLC (a U.K.-based company that has made a series of discoveries offshore Cameroon) has completed the geological and geophysical work onshore, which contains a Tertiary gas discovery and undrilled analogue prospects as well as deeper undrilled Cretaceous leads analogous to a producing field immediately to the south.

Proven reserves onshore with a large upside fits most companies’ search criteria, although natural gas prospects in Cameroon may not be at the top of their lists. Natural gas has a limited local market, but the new export route available once Bowleven’s offshore development is under way will change the prospect dramatically for near-term cash flows from onshore gas development. This is a good example of the highly prospective opportunities available to companies willing to look in detail at projects that today are considered unfashionable, but before success is proven and other competitors arrive.

Long-Term Plan

Formulating a clear medium- to long-term plan with plenty of time, money with contingency and the flexibility to achieve it, while understanding a basin’s geology and becoming familiar with a country’s culture are essential to succeeding in international projects. Even within a country, there can be significant cultural divides between one region and another. Taking the time to make sure differences are understood and expectations are managed correctly is crucial in international operations.

Having people on the ground very early in the process of expanding into a new region or country with the involvement of local people typically results in substantial long-term benefits and cost savings. In fact, it can mean the difference between success and failure for some projects. Fostering an understanding of local cultures and building trust with experienced and reputable people in-country with technical, legal, accounting/tax, commercial, engineering and political knowledge are as important as geology, geophysics and engineering.

There are large rewards for successful international exploration, albeit with a step change in the cost of doing business in foreign lands, higher commercial risks, often much longer lead times, and considerations to local cultures and business customs. The opportunities for U.S. independents in international projects are vast. With the right approach to international expansion, independents can replicate the success of projects such as the Jubilee Field offshore Africa or the Noble Energy-operated Leviathan and Tamar giant discoveries in the Mediterranean Sea. Ultimately, independents can play a new pioneering role in developing both conventional and unconventional resource plays around the world.

MIKE LAKIN is founder and owner of London-based Envoi Limited, a consultancy that assists companies in international acquisition and divestiture activities. He began his career at Superior Oil in 1984, and then joined a small U.K. independent exploration company as a geologist involved in operations, and the exploration and discovery of oil in the Weald Basin onshore southern England. He transitioned to the international A&D services sector with Petreseach in the early 1990s, before establishing Envoi Limited in 2000. He holds a degree in geology from Cardiff University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.