Price Fundamentals

‘Lower For Longer’ Forecasts Based Largely On Sentiment, Not Oil Market Realities

By Allen Gilmer

AUSTIN, TX.–The one given in the unpredictable oil and gas industry is that “consensus analysis” about where the price of oil is going over the near to intermediate terms is consistently wrong. Just as $100 oil was a sentiment-driven price that baked in the risk of every potential negative impact on the supply chain, $28, $30 and $40 oil are equally sentimental, assuming that any and all incremental barrels will be available, and that demand will slow or stop altogether.

While those inside the industry get it, more and more analysts outside the business are lining up behind the lower-for-longer sentiment, although there is some disagreement about what price level constitutes “lower” and what time frame is meant by “longer.” But to step away from all the noise, there is a noncontroversial outcome to the current market environment: Oil will be much more valuable in the future than it is today.

What, exactly, will that future look like? Today’s pricing sentiment is driven by a “pick six” of global economic factors:

- U.S. production rates;

- Saudi Arabia’s ability (or lack thereof) to grow production;

- Iran’s latent ability to produce more oil with the lifting of international sanctions;

- China’s economic slowdown and its impact on consumption;

- Russia’s ability to add global production; and

- The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ inscrutable strategy.

Before getting into these issues, let us stipulate a couple key assumptions:

- Producing companies and/or nations will produce existing wells at rates that are not sustainable to preserve cash flow or compete for market share because the cost to drill and bring new production on line is sunk already.

- New wells will not be drilled if there is not at least an outlook to break even producing them. That means an expectation of a sustained price over one-three years, or until the well has been paid out.

Sloping Foundation

The simplest and most transparent of the pick six issues being bandied about as a price driver is U.S. oil production, specifically the supposed resiliency of onshore tight oil resource plays. Certainly, the unconventional revolution has been a huge factor in global production increases. However, the item not generally recognized is that production typically lags drilling by some five months, so that drilling in December 2014 is discernible in production records in April 2015. That analysts were alarmed at increasing production and supply during the first half of last year suggested that they did not understand this dynamic, nor did much of the American business press.

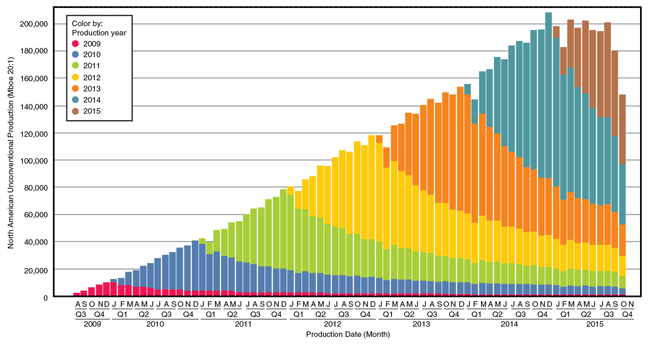

Figure 1 shows production from U.S. onshore unconventional plays over the past six years. Note that the lag in production reporting means fourth-quarter 2015 reports, and even some third-quarter 2015 reports, are not finalized. Drillinginfo’s analysis predicted in April 2015 that monthly production would peak in May, and then jump around between net declines of 100,000 and 350,000 barrels a day for the rest of the year.

When looking at additional production month over month, it is important to remember that it is building on a sloping foundation of natural decline. For instance, in 2014, as U.S. supply added some 1 million barrels of daily production, it had to produce 2.2 million new barrels a day of oil production to do so. The slope of that foundation required 1.2 million new barrels a day simply to flatten the decline curve.

First-year U.S. oil production has had a blended annual decline that has increased from 41 percent for 2010-era wells to 47 percent for 2013-era wells. Therefore, wells drilled in 2014 were likely to have declined by 49 percent in their first year of production, and 2015 wells by 51 percent. Second-year declines show less of a pattern, ranging from 10 to 20 percent from the end of the prior year.

Real Production Declines

In other words, we will see real production declines in 2016 as the full impact of severe 2015 drilling reductions is cycled through. Depending on the variability of second-year declines, the amount of U.S. oil production lost by the end of this year could range from 400,000 bbl/d to more than 1 MMbbl/d (and this will come on top of the production lost in the second half of 2015).

Lending clear support to projected production declines, the February Drillinginfo Index showed U.S. new production capacity (NPC) for both oil and gas falling by a whopping 24 percent, to 475,000 barrels oil equivalent a day (from 621,000 boe/d in January). Looking at crude oil only, U.S. NPC decreased 12 percent in February, to 261,000 bbl/d. The index is reflective of wells drilled in the previous month and is usually a forward indicator of what production may be in five to six months.

So, given the marked slowdown in new oil production capacity, and the impact of decline rates on the existing production base, the United States is not going to be the bringer of “oil glut news” going forward, and should not drive a low-price sentiment. In fact, the domestic oil patch has severely damaged its capacity to rebound from an oil field services point of view, with companies foregoing normal maintenance simply to survive. This deferred maintenance will have permanent consequences.

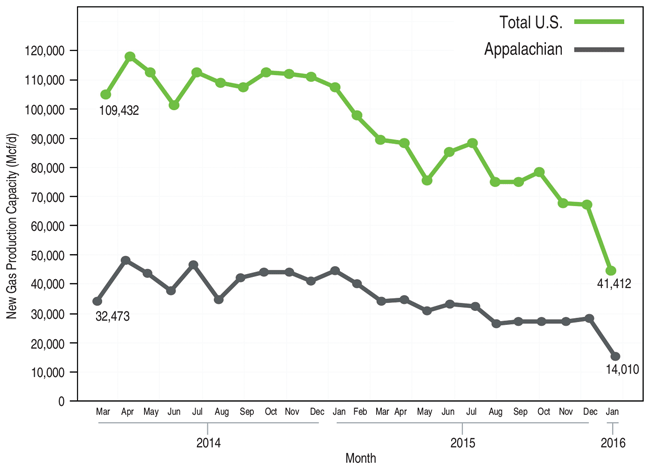

It should be noted that the February Drillinginfo Index found an even more precipitous slide in new gas production capacity, with natural gas NPC falling 35 percent, to 1.28 billion cubic feet a day. Since May 2014, U.S. natural gas NPC has decreased by 58 percent, with a continuous decline in the Appalachian Basin leading total U.S. gas NPC on a downward slope since March 2014 (Figure 2). The new absolute low in the Appalachian Basin may show the beginning of the capitulation that some observers think may lead to the firming of market prices and a rebalancing of the North American natural gas market.

FIGURE 2

Total U.S. versus Appalachian New Natural Gas Production Capacity Declines (March 2014-February 2016)

Supply, Demand Perceptions

How about the perception that Saudi Arabia has the ability to further grow its production? Whereas Saudi Arabia’s rig count is up, so is its production, which reached record amounts in 2015. The world’s one-time “swing producer” has been effectively producing at capacity, and most industry experts believe there is little, if any, behind-valve spare production. Any sudden interruption in global supply likely could not be met by additional Saudi production, causing today’s perceived supply glut to become a shortage.

When sanctions hit Iran, the country immediately dropped 600,000 bbl/d from its official oil production levels. The fact that the Iranians are reporting the same production (to the barrel) since then causes that official number to be quite suspect. Iran has not been investing in its infrastructure, and it requires outside dollars to reinvest in existing production.

The necessary capital investment ranges from $30 billion to $500 billion over the next five years, depending on the source, to simply maintain existing production. Oil priced at $30/bbl is not an environment amenable to outside tender offers.

Some claim there will be no net new production in the near term, and that Iran merely will start to recognize the oil production it previously sold on the black market. In any case, 500,000 bbl/d of new Iranian oil production remains baked into most supply forecasts. Score another one in the “not-a-driver” category.

The Chinese economy has been exhibiting signs of extreme duress, suggesting that demand growth could weaken materially. Imports of metals and building materials are down substantively, but oil imports are not. China continues to import crude oil at increasing rates, most likely taking advantage of the low-price environment to strengthen its strategic reserves. China’s growing “guns versus butter” investment shift is not likely a bearish sign for crude oil, either.

Production growth estimates from both the International Energy Agency and the U.S Energy Information Administration suggest that the market is not going to respond elastically to lower oil prices. In essence, IEA and EIA are saying that lower prices will not drive higher consumption for the first time in history, despite the “surprise” increase in global consumption in 2015. That is four nondrivers.

Let us make it five. Russia found itself in a fun position in 2015 as economic sanctions hammered the value of the ruble by 50 percent. Essentially, Russia had a half-price drilling environment and was effectively hedged by its cratering currency because it pays for new wells in rubles and sells its crude in dollars. This advantage no longer exists with commodity prices at the levels seen to date in 2016. Russia is not likely to spend $1.00 to get back $0.20 in the first year.

Wielding The Big Stick

Forget the rest of the “pick six” factors. If anyone assumed OPEC was not in charge of global oil prices, he was dead wrong. And by OPEC, let’s be honest, and say Saudi Arabia. Only Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States technically have the production base to unilaterally affect the price of crude without completely undermining their net production rates, and the U.S. regulatory environment is focused on efficiency and safety, not price (until recently, the United States alone among these three nations was thought to be a net beneficiary of low-priced crude oil).

Tired of being the only player ceding market share in an organization composed of members that continually and habitually cheat on their production allotments, Saudi Arabia is flexing its global geopolitical muscle to enforce its control over the organization and affect the amount of money available to global exploration, drilling and production projects in light of the new beta in crude oil pricing that is recognized today.

So, as a result, the United States finally sees production declines in the celebrated unconventional resource plays, and Iran and Russia are starved of cash along with the rest of OPEC’s members, some to the point of existential crisis. How big a stick does Saudi Arabia wield right now? Very big, I think, making OPEC’s strategy a definite major market driver.

So what about the U.S. oil patch? Global crude oil is priced as ridiculously today as it was at $120/bbl. A 2 percent “oversupply” in a world where one cannot even measure actual supply with any certainty within 5 percent drops the price of crude more than 70 percent. It also has every analyst who claimed only two years ago that we would never again see oil below $100/bbl now claiming that we will not see oil higher than $40/bbl anytime soon. They were wrong then, and they are wrong now.

What is different is that the cost of capital in the United States has gotten much higher. That will not be changing soon. Banks and other lenders already have started changing the cost of capital. Warrants are being demanded at closings. Even when oil recovers, this will not change rapidly.

Watch the industry get a lot better because its break even for cost of capital will have gotten worse. The oil field services sector has suffered more than a glancing blow. It will not be able to ramp up as quickly as it was laid down. A lot of its equipment is shot for lack of proper maintenance.

The Federal Reserve is reported to be advising banks to push for asset liquidation in lieu of bankruptcy. This is actually a good idea, if the point is to preserve value for lenders and equity holders. There is nothing more damaging to producing oil and gas assets as a bankruptcy trustee.

Great for the eventual acquirer, bankruptcy trustees know how to make sows ears from silk purses by their reluctance to fund what Texas Independent Producers & Royalty Owners Association Chairman Raymond Welder calls the “recurring, nonrecurring” expenses such as the workovers necessary and common in the oil field.

Allen Gilmer is co-founder, chairman and chief executive officer of Drillinginfo. He is active in all aspects of Drillinginfo’s new product development and is widely recognized for his industry leadership and vision. Gilmer holds several patents in multicomponent seismology. He received a B.A. in geology from Rice University and an M.S. in geology from The University of Texas at El Paso.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.