Permit Process Key To Project Success

By Greg Newman and Brad Stevener

HOUSTON–The past decade has seen many local, state and federal rules enacted that regulate the oil and gas industry. These regulations cover, among other things, land usage, produced liquid storage/disposal, storm water, spill prevention, emergency response plans and emissions during site development and operation.

It is vitally important to address environmental due diligence in the early stages of project development, because if not properly accounted for, violating environmental regulations can have potentially harsh consequences, including delays to construction or operations at a site, resulting in lost revenue.

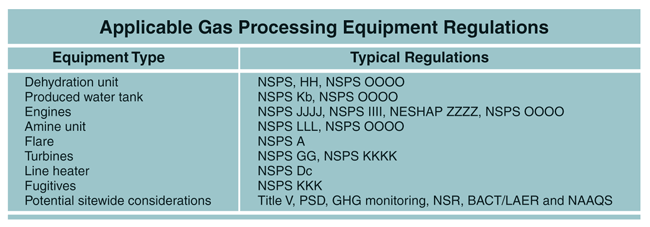

The industry seems to be awash in regulations. As if they were not difficult enough to understand in the first place, federal air quality regulations can resemble a bowl of alphabet soup with their myriad of letters–NSPS, NESHAP, PSD, NSR, etc.–sometimes followed by subsections such as ZZZZ, OOOO, JJJJ, HH, Dc and Kb. Confusing? Definitely.

This article touches on the environmental regulations affecting domestic oil and gas projects by focusing narrowly on the air regulations that influence the selection of natural gas compression equipment at a typical booster station or natural gas processing plant.

Table 1 shows typical equipment that would be found at a natural gas processing plant, along with potentially applicable air regulations. This listing is not meant to be all inclusive and is only a sample of regulations that apply to various equipment. It is not our intent to discuss all of the environmental regulations affecting each of the various types of oil and natural gas facilities. Other equipment has similar regulatory restrictions. Of course, all segments and facility types are included under the umbrella of oil and natural gas operations, and are governed by different sets of environmental regulations.

Early Determination

It is essential to define the facility and diagnose the impacts of the applicable environmental regulations as early in project planning as possible, since one piece of equipment can trigger different regulations and have very different environmental requirements, depending on the type of facility in which it is used and where it is physically located.

In fact, determining which rules affect the project’s equipment and their implications is critical. Navigating the applicability of those rules and different permit types can lead to selecting different equipment than that which was originally envisioned for a location.

When considering equipment selection for natural gas compression, there are several issues the “environmental person” must evaluate to determine the type of equipment needed. The exact location and a list of all expected equipment at the site are the first critical pieces of information. But producers should be aware that different states, let alone counties and cities within the same state, can have different environmental regulations that must be evaluated for applicability, along with any germane federal regulations. Clearly, advance planning is paramount.

The location could be in a nonattainment area, on tribal lands or even offshore, each of which has specific mandates for equipment. An initial estimate of emissions for the project will give an indication of where the site lies in relation to being a “major” source. The definition of what is considered major is not a one-size-fits-all answer. The threshold for the amount of potential emissions that trigger the definition of a major source can vary per pollutant and per geographic location.

Nonattainment areas have lower emission thresholds for those pollutants that cause the areas to be considered nonattainment. There are five categories of nonattainment, with each having different thresholds (extreme, severe, serious, moderate and marginal). Nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon (CO), particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), individual hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) and collective HAP emissions each can cause a site to be considered major or trigger it to become a Title V source. However, there are benefits to avoid becoming a major or Title V source.

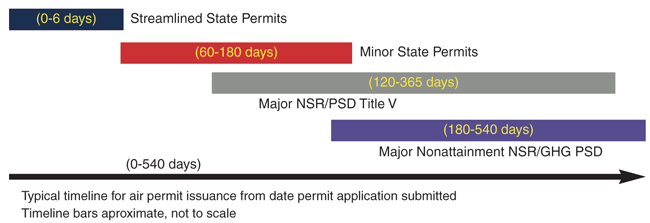

Depending on the total site emissions, it may be preferable to select certain controls and equipment to classify the facility as a “minor” source, and avoid enduring a lengthier permitting timeline (and having to submit a more complicated permit application, which could include atmospheric dispersion modeling). When proceeding through minor source permitting, there can be differing lengths of review times and application complexity that can vary based on engine size, location, and of course, local regulations.

Permitting Timelines

Sources that require major or Title V permitting typically have increased reporting and record keeping responsibilities for the owner, as well as additional scrutiny from environmental agencies (i.e., increased compliance obligations). If the increased requirements of a major permit are not a deterrent, the increased time frame may be.

Figure 1 shows a generalized timeline for issuing various air permit types to illustrate how the permitting route can dictate project timing. As permitting becomes more complex, the review time increases, as does the uncertainty of time to obtain a permit. Furthermore, construction typically cannot begin until an air permit has been issued.

A site that is a major source for greenhouse gas emissions, for example, could take anywhere from 180 to 540 days to permit. Working closely with the agency reviewing the permit will give applicants a better feel for a timeline, but the large deviation in review time can wreak havoc on a project’s timeline to completion.

Traversing the permitting process for the “here and now” can be frustrating, but the oil and gas company operating a project should not forget about the extended plans for the site. Regulators can investigate any indication that a project’s construction was staggered or the permitting was done in such a way to circumvent the rules. For projects that will be developed in phases, it is a good idea to hold a preapplication meeting with the permitting agency to get approval on the permitting strategy and address any concerns about the schedule being influenced by reduced permitting or compliance obligations.

Along with circumvention, potential aggregation with nearby facilities is something a company should evaluate and address in the permit application. Aggregation is the inclusion of any nearby sources that should be considered as part of the same site or connected in such a way that would require them to be accounted for within the same air permit. Concerns by the public or an agency that aggregation or circumvention was not properly addressed in the permit application can lengthen a permit’s review time and/or trigger a public hearing, which can delay construction and operation.

Equipment Performance

A gas analysis is one of the next things to evaluate, along with site elevation and climate. All of these can affect equipment performance and emissions. Hydrogen sulfide, methane number and Btu content can affect equipment selection because of their impacts on the emissions profile. High elevation or extreme temperatures can cause an engine to be operated at a lower load than the nameplate horsepower rating. Understanding these variables is crucial to selecting the proper size of equipment needed.

When planning upstream and midstream projects, such as this El Paso-operated amine treating facility in Louisiana, it is essential to define the facility and diagnose the impacts of the applicable environmental regulations as early as possible, determining which rules affect the project’s equipment and their implications. As permitting becomes more complex, the review time increases, as does the uncertainty of time to obtain a permit.

When selecting a driver for a compressor, there could be reason to consider electric motors, gas-fired turbines or gas-fired rich-burn or lean-burn reciprocating engines. Each of these has a different fuel efficiency and emission profile. Depending on the other equipment in the permit application, one type could be more suitable in limiting emissions such as greenhouse gases, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde and other pollutants.

For example, a natural gas-fired engine can have a catalyst installed in its exhaust stack, which reduces emissions of certain pollutants. A lean-burn engine can have an oxidation catalyst installed to reduce CO, VOC and formaldehyde, while a catalyst designed for a rich-burn engine (a three-way catalyst) can reduce these pollutants, as well as NOx. More catalyst elements can be installed if greater emission reductions are needed. Selecting the proper number of catalyst elements, while keeping engine backpressure manageable, is a crucial step.

On top of all this, there are controls that can either be required or voluntarily applied to reduce overall site emissions. Reasons to voluntarily reduce emissions include simplifying the permitting process and being a good corporate citizen. Some of these emissions reductions include capturing and controlling fugitive emissions, emissions from blow downs, or any equipment or process that vents natural gas to the atmosphere.

After the compressor driver has been determined, knowing specifics about available engines, turbines or motors is necessary. If natural gas engines are chosen, for example, the horsepower of each engine configuration and its dates of construction, manufacture, and reconstruction or modification, if applicable, are key. Why? These dates are critical in determining the applicability of the new source performance standards for stationary spark ignition internal combustion engines JJJJ and national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants (NESHAP) for reciprocating internal combustion engines ZZZZ regulations. NESHAP ZZZZ is also often referred to as “RICE MACT.” Mind numbing, isn’t it?

Yet, once it is known which regulatory requirements govern each engine, motor or turbine, figuring out which units will comply in the field can be accomplished relatively easily. Then a determination can be made as to which configurations of the available engines will give the best design and/or fastest permitting lead time.

Committing to the environmental permitting process early helps oil and natural gas project managers navigate the complicated regulatory maze. And the steps defined in this article can significantly streamline environmental permitting efforts and help projects get on line as soon as possible.

Conversely, beginning construction on a facility prior to completing the permitting process can lead to fines from the regulating agencies and/or cause the site to be shut down until it is properly permitted or until equipment can meet the applicable regulations. All the while, time and money are lost. None of these outcomes is acceptable for an oil or natural gas project, especially when they can be prevented with proper planning.

In the ever-changing landscape of environmental regulations, one thing seems certain: Complexities with respect to environmental impacts will increase. Being mindful of these regulations when starting to plan for facilities is vital and highly beneficial.

GREG NEWMAN is director of environmental services for Valerus in Houston, where he oversees environmental support for overall business operations, including manufacturing, aftermarket services, integrated services and asset management. Along with his 15 years of extensive experience in all levels of air permitting across the United States, he has provided overall environmental support in upstream, midstream and downstream oil and gas operations, as well as conventional and nonconventional power generation. Newman holds a B.S. in civil and environmental engineering from the University of Houston and an M.S. in environmental engineering from the University of Texas at Austin.

BRAD STEVENER is manager of environmental services for Valerus in Houston, where he manages corporate environmental compliance with a focus on asset management, the company’s fleet of contract compression equipment. With 15 years of experience in the environmental field, including state, consulting and industry experience, Stevener has expertise in power generation, compression, and all aspects of oil and gas operations. He holds a B.S. in agricultural and environmental engineering from Texas A&M University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.