Technology And Innovation Are Keys To Success In Emerging Tight Oil Plays

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

The name of the game is no longer just finding emerging tight oil plays. Companies are doing a remarkable job of that. No, the name of the game today is finding ways to make all the new resource plays economical.

“Everyone is taking known working solutions and finding places to apply them,” assesses Kevin Beiter, president and chief executive officer of Central Montana Resources, one of the pioneers in the Heath Shale, an oil resource play in Central Montana that is one of numerous new plays attracting the independents that are driving the nation’s increasing oil production.

Horizontal drilling and multistage hydraulic fracturing are being used to unlock numerous emerging plays from the Cline Shale on the eastern flank of the Permian Basin to the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale in Louisiana and Mississippi, the Utica Shale in Ohio, the Heath Shale in Montana, and the Smackover/Brown Dense formation in northern Louisiana and Arkansas, to name a few.

“You get an idea,” reflects Rick Bott, president and chief operating officer of Oklahoma City-based Continental Resources, the Bakken’s leading leaseholder. “You try it and derisk the play, and then it will play out over the next two decades. There are a lot of things to do. I look at the unconventional part of our business as a technology business.

“All the major fields of the last 100 years can be revisited,” marvels Bott, referring to the potential offered by the industry’s new technology.

SCOOP

While Continental Resources was going gangbusters in the Bakken Shale, Bott says slumping natural gas prices forced the company to go a different direction in another region, resulting in the discovery of what it calls the South Central Oklahoma Oil Province, or SCOOP.

The South Central Oklahoma Oil Province (SCOOP) presents a drilling challenge, and geosteering is critical to target four- to eight-foot intervals. Continental Resources finished 2012 with six rigs operating in the new play, and says it expects to average 12 rigs this year, finishing 2013 with 17 rigs.

“In the latter part of 2011, gas prices started heading in the wrong direction,” he recalls. “We told our southern team members we couldn’t continue to fund the Northwest Cana (natural gas play in Oklahoma). We told them they had to retool to compete with the Bakken for capital.”

That is exactly what they did.

The SCOOP play covers much of four counties in south-central Oklahoma. The rock is an oil-rich portion of the Woodford Shale, and lies beneath oil fields that have produced from 60 conventional reservoirs over the years. Continental Resources says it believes SCOOP has the potential to produce 3.2 billion barrels more from the immobile phase using horizontal drilling.

“They determined there was a lot of oil in place in the basin (southeast of the Northwest Cana Field), but the conventional wisdom was this was more gas prone,” Bott says. “They found success and we built a stealth lease position, acquiring 197,000 acres. We drilled 35 wells to get an idea where the thoroughfare was. The economics can compete with the Bakken.”

The SCOOP play covers much of four counties in south-central Oklahoma. The rock is an oil-rich portion of the Woodford Shale that lies beneath oil fields tapped by some of the state’s biggest names, including Phillips, Noble, Hefner and Skelly, Bott explains.

He says the SCOOP is 65-75 percent liquids at depths of 9,000-14,000 feet. The oil-rich rock is 150-400 feet thick, and he says it gets thicker as one goes southeast, adding that it is silica rich, which is important for fracturing. Estimated ultimate reserves, according to Bott, are 1.1 million-1.2 million barrels of oil equivalent in the condensate window and 625,000 barrels of crude oil per well.

“We learned a bunch of lessons from the Bakken that helped cut the (SCOOP) learning curve,” Bott continues. “You are going for the source rock, and there is a lot of oil left, but it is a very challenging interval to drill. Where you land and how you fracture it is important.”

Bott says Continental has done a little seismic to understand the key reservoir, but geosteering, which allows the company to target four- to eight-foot intervals, is critical.

“We have built an outstanding team,” he lauds. “We work with the drilling guys on developing new drill bits and new fluids. There is a lot of rapid application of learning.”

Bott says Continental still is allocating 66 percent of its capital budget to the Bakken Shale, but it is putting 15 percent into the SCOOP. The company finished 2012 with six rigs operating in the new play, but he says it will average 12 rigs this year, finishing 2013 with 17 rigs.

The area in Stephens, Grady and Carter counties in south-central Oklahoma has produced oil from 60 conventional reservoirs over the years, but Bott says he believes SCOOP has the potential to produce 3.2 billion barrels more of oil from the immobile phase using horizontal drilling.

Joint Venture

Perhaps no company has jumped into new tight oil plays in a bigger way than Oklahoma City-based Devon Energy. The company signed a pair of joint venture agreements totaling nearly $4 billion last year to help fund its exploration of the emerging plays.

First, Devon signed a $2.5 billion joint venture agreement with Sinopec, a Chinese petrochemical company, says Chip Minty, manager of media relations. That deal gives Sinopec a one-third stake in five of Devon’s U.S. plays: the Mississippian Lime, Niobrara, Utica, Tuscaloosa Marine, and Michigan. Then in September, Minty adds, Devon closed a $1.4 billion deal with Japan’s Sumitomo Corp. to give Sumitomo a 30 percent stake in 650,000 net acres in the Permian Basin that are prospective to the Cline and Midland-Wolfcamp plays.

“The joint ventures allow us to bring in partners that are willing to pay for the majority of the initial exploration in these new plays,” Minty observes. “There is considerable drilling activity and cost required to develop these plays. By utilizing a joint venture, we are able to use the resources of our partner to explore these new plays while leaving our capital to focus on core areas where we have development and production, and can continue growth.”

In Devon’s third-quarter earnings conference call, Dave Hager, executive vice president for exploration and production, addressed some of the company’s early results in the emerging plays.

Devon announced its third-quarter Permian Basin production averaged a record 65,100 boe a day–a 30 percent increase over the same period a year ago. That includes the company’s Bone Spring horizontal program in New Mexico, as well as the Delaware Basin oil play in far West Texas and the Wolfcamp Shale in the southern Midland Basin. Hager says Devon brought five Wolfcamp horizontal wells on line in the third quarter.

In addition, Hager says Devon is steadily ramping up drilling activity in the Cline Shale on the eastern flank of the Midland Basin, where the company is running four operated rigs.

“This acreage is prospective for the Wolfcamp and the Mississippian formations, in addition to the Cline Shale,” Hager points out. “We tied in our second Cline horizontal well during the third quarter and saw encouraging results. The Virginia City Cole C1H, located in Sterling County, Tx., had a 30-day initial production rate of 450 boe/d.”

He added that Devon’s third Cline horizontal well was just starting to flow back in November, and the company had five additional wells in various stages of completion, including one well targeting the Mississippian. The 556,000 net acres in this area of the Sumitomo joint venture represent thousands of risked locations, Hager points out.

Emerging Plays

Devon has active development programs targeting oil windows in the Cana Woodford Shale in western Oklahoma, the Barnett Shale in North Texas, the Granite Wash in the Texas Panhandle, the Powder River Basin in the Rocky Mountains, and the Ferrier Corridor of Alberta, but Hager says the joint ventures have allowed Devon to look at the emerging plays with “very little impact from a new capital perspective.”

He says the company’s results in the western oil window of the Utica Shale in Ohio have been disappointing, causing Devon to shift drilling efforts further to the east. It planned to have three or four wells drilled on the more eastern acreage by year-end.

“In the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale, we tied in our third and fourth wells in the northern portion of our acreage position during the third quarter,” Hager continues. “The Murphy 63H, located in West Feliciana Parish, La., had an average 30-day IP rate of 260 boe/d from a 4,700-foot lateral. Roughly 40 miles to the east in Tangipahoa Parish, La., the Thomas 38H had a 30-day IP rate of 470 boe/d from a 4,900-foot lateral. We would need to see improvements in both costs and recoveries to make this an attractive play going forward.”

Devon has 13 operated rigs running and 545,000 net acres in the Mississippian Lime oil play in north-central Oklahoma. The company had 20 operated Mississippian producers awaiting completion, according to Hager, although Devon did bring on the Bontrager 1-28H in the third quarter with an average 30-day IP rate of 545 boe/d, including 480 bbl/d oil.

“These results continue to support a type curve with a 30-day IP of roughly 300 boe/d and an estimated ultimate recovery of 300,000-400,000 boe at a cost of $3.0 million-$3.5 million per well,” he relates. “Our 545,000 net acres represent many years of drilling inventory for us. We estimate the risked resource potential net to Devon at more than 800 million boe.”

Cline Shale

The story of the remarkable growth in the Permian Basin has been stacked pays. First, it was the vertical Wolfberry wells that fractured and commingled the Spraberry and Wolfcamp formations, as well as multiple zones below the Wolfcamp.

Then operators began drilling horizontal wells in the Bone Spring and Avalon Shale in the Delaware Basin in far West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. Next, companies turned the drill bit on its side in the Wolfcamp Shale, in some areas drilling horizontal wells in the same region in which they had been drilling successful vertical Wolfberry wells.

Now, the Cline Shale is sparking excitement on the Permian Basin’s eastern flank. The Lubbock Avalanche-Journal reported on Nov. 29 that “hopes are high for (developing) the Cline Shale in West Texas, with some lofty estimates suggesting the Cline could be the biggest oil play in U.S. history. Based on test well results, estimates are the Cline may contain 3.6 million barrels of recoverable oil per square mile and 30 billion recoverable barrels for the entire play.”

Only time will tell whether those grandiose predictions are accurate, but Randy Foutch, chairman and chief executive officer of Tulsa-based Laredo Petroleum, says he is thrilled to be one of the leaders in the Cline, especially since his company’s 142,000 acres in northern Reagan, Glasscock and southern Howard counties, Tx., have the potential for horizontal drilling in both the Cline and Wolfcamp.

“That is what excites us,” exclaims Foutch. “When we bought this acreage, we developed the theory that there were multiple horizontal zones. The Cline, which is currently the deepest, and the Lower, Middle and Upper Wolfcamp are all overlapping. Now that we have production from a number of wells–33 in the Cline, 16 in the Upper Wolfcamp and a couple in the Lower and Middle Wolfcamps–we have found our theory is real.”

He says Laredo has completely derisked its vertical Wolfberry program. “We also have derisked 70,000 acres in the Cline and 60,000 in the Upper Wolfcamp to date,” Foutch adds. “The rest has a good chance of being derisked, and that doesn’t even count the Middle and Lower Wolfcamp. This has huge potential.”

Perfecting The Technology

Laredo Petroleum was the first to drill horizontal wells in the Cline, according to Foutch, after acquiring acreage in 2008. “We cored our wells in 2009 and we got great 3-D seismic,” he explains. “We have more than 700 vertical wells, and 250 were drilled deep. If you would have told me five years ago that I had 3,500 vertical wells to drill with a decent rate of return and repeatability, and I would be trying to drill as few as possible, I would have told you that you were crazy.”

Tulsa-based Laredo Petroleum is one of the leaders in the Permian Basin’s Cline Shale with 142,000 acres in northern Reagan, Glasscock and southern Howard counties, Tx. The company says its acreage is prospective in multiple zones: the Cline, and the Lower, Middle and Upper Wolfcamps.

Laredo Petroleum is drilling 7,000- to 7,500 foot laterals in the Cline Shale and completing with 24-26 frac stages. The company reports wells making 600-900 barrels of oil equivalent a day on an initial 30-day average.

But that is what horizontal drilling in the Cline and Wolfcamp has done. Foutch says the big question is how far east the Cline Shale play will extend. Some predict it could go as far as Abilene, Tx., approximately 100 miles east of Laredo’s acreage.

“We bought our acreage in a specific window, about 80 miles long and 20 miles wide,” Foutch offers. “We like our acreage block, but that is not reflecting on what else is there.”

He says Laredo began drilling 4,000-foot laterals with 10-stage completions, but then the industry recognized the need for longer laterals. Laredo now is drilling 7,000- to 7,500-foot laterals with 24-26 frac stages.

“The EURs of these wells are still confusing,” Foutch acknowledges. “We report only crude oil and natural gas, but not NGLs. Our long-lateral wells are making 600-900 boe/d on an initial 30-day average.”

Laredo is running three to four horizontal rigs and four to six vertical rigs on its acreage, although Foutch says the number of rigs is less important to capital expenditures than it used to be because two-thirds of the cost is stimulation.

The ability to drill and fracture long-reach laterals may be the most significant developments in the history of the industry, according to Foutch, especially on its acreage, where Laredo has established four horizontal zones. “We know we have a 1,300- to 1,800-foot section of producible shale oil in four zones,” he claims. “That is dramatically more than anything else out there. That is pretty significant.”

Patience Is A Virtue

Kirk Barrell, president of Amelia Resources, writes a blog about the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale called Tuscaloosatrend.blogspot.com. Through joint ventures, his company has acquired a leasehold of 125,000 acres prospective to the Tuscaloosa Marine, on which Amelia retains an overriding royalty interest. None of the acreage has been drilled yet, he says.

“We are patiently waiting for our turn,” he explains. “We don’t want to be in the experimental stage. Wells in these new plays tend to get better as time goes on.”

The Tuscaloosa Marine sits above the Tuscaloosa Sand. Because of that, Barrell, who has spent 23 years working the Tuscaloosa trend–five of them with Amoco–says there is a lot of data as well oil and gas shows from this known source rock. There have been questions, however, about water and the clay content of the Tuscaloosa Marine.

“Devon was the first to start leasing (in late 2010),” he relates. “We teamed with Encana when it kicked off an exploration program. EOG Resources, Goodrich Petroleum and Halcon Resources also are drilling actively. There were 14 completions in the latest phase in 2011-12.”

Although the play is very much in the early stage, Barrell claims there have been two industry tests with IP rates of more than 1,000 boe/d.

“Everyone is waiting 12 months to find out what the decline curve will look like,” he continues. “The majority of it is oil, with a gas-to-oil ratio in a range of 400-to-850.”

The Tuscaloosa Marine Shale is deeper than most of the new plays. Completions are at vertical depths of 12,000-14,200 feet, according to Barrell. He says the play could include as many as 7 million acres, spanning from Central Louisiana into southwestern Mississippi.

Shorten Learning Curve

Encana Corporation is hoping to use what it has learned in other horizontal plays such as the Haynesville Shale and the Horn River Basin to shorten the Tuscaloosa Marine learning curve from four years to 18 months, according to Danny Dickerson, the team leader for oil development in the Mid-Continent business unit in Encana’s Plano, Tx., office.

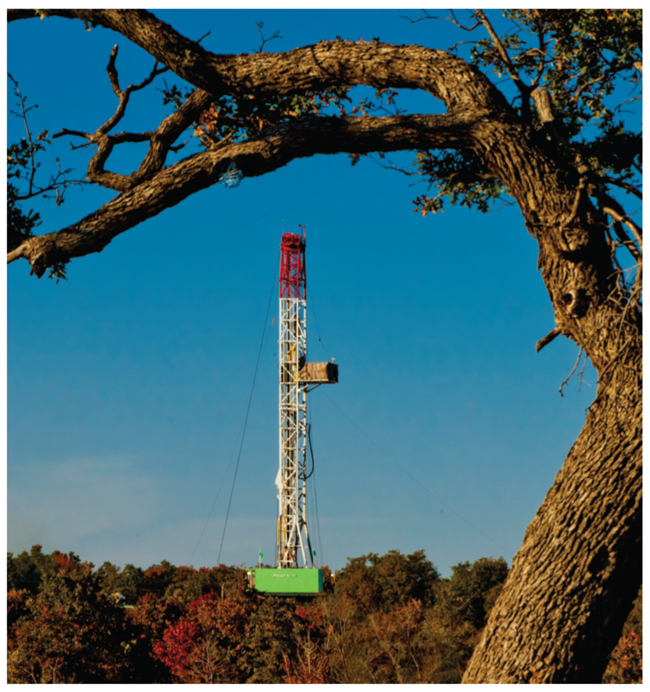

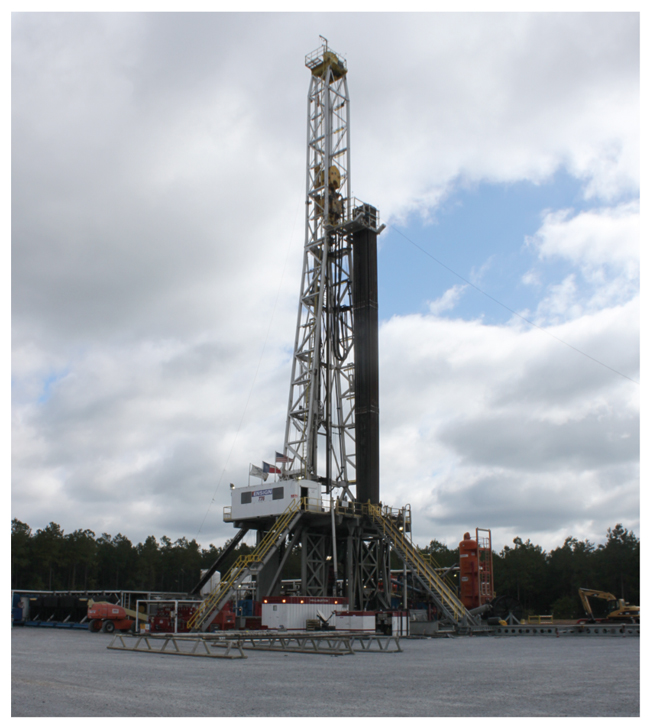

Encana Corporation has 355,000 net acres in the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale in both Louisiana and Mississippi. The company reports wells such as the one shown here in Amite County, Ms., produce a sweet crude that commands Louisiana Light Sweet pricing.

Encana Corporation drilled its Weyerhaeuser 73 well in Helena Parish, La. The company says it has completed lateral lengths of 5,000-8,755 feet and expects to settle on 7,100-foot laterals with 30 fracture stages, although the best drilling, production and completion methods are evolving.

“We have 355,000 net acres in the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale in both Louisiana and Mississippi,” Dickerson states. “We have drilled eight horizontal wells. Three were waiting on completion (as of December). We have one rig active in the play. We are in the early stage, but we are seeing improved performance with every well. We had a 30-day IP rate of more than 1,000 boe/d on one well.”

Encana has completed lateral lengths of 5,000 to 8,755 feet. “We expect to settle on 7,100-foot laterals with 30 frac stages, but the best drilling, production and completion methods are evolving,” Dickerson continues. “We are seeing a relationship between stimulation size, and production and EUR numbers.”

The Tuscaloosa Marine is an organic shale with depths ranging from 11,500 to 15,000 feet, according to Dickerson. “It is a little deeper than other horizontal plays,” he observes, “but the bottom-hole pressure is only 240-280 psi, so it is not a hot-hole situation. The challenge is well bore stability, which has caused initial wells to be higher cost. We have identified the better place to drill to get well stability, and our last two wells were trouble free.”

One advantage to the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale, according to Dickerson, is that it is sweet crude that commands Louisiana Light Sweet pricing. He says the wells produce 97 percent oil and natural gas liquids.

“The Tuscaloosa Marine Shale is stratigraphically equivalent to the Eagle Ford and Eaglebine formations, which have been penetrated by thousands of well bores,” he comments.

Eaglebine is the name that has been given to a horizontal drilling program in Robertson and Brazos counties in East Texas that combines an expanded section of the Woodbine Sands and the Eagle Ford Shale formations. There were 10 rigs running in the Eaglebine in December, counts Dickerson, who says Encana has 115,000 acres prospective to the Eaglebine.

“We have drilled and completed eight wells,” he reports. “Most operators focus on the Woodbine Sands, but the horizontal wells do much better.”

Heath Shale

Central Montana Resources, a privately held company with corporate headquarters in San Antonio, was the first to begin acquiring leases in the potential Heath Shale play in 2007, and drilled its first well in 2010. President and CEO Kevin Beiter says his company has drilled 10 vertical and four horizontal wells.

“We have learned a great deal, but there is a lot left to learn,” Beiter allows.

CMR has accumulated about 484,000 net acres north of Billings, Mt., in Fergus, Petroleum, Garfield, Rosebud, Musselshell and Golden Valley counties. Beiter says the Heath Shale is a known source rock that has produced 150 million barrels of oil in the Tyler and other formations through the years. Now, he says, technology is allowing the industry to exploit the Heath Shale itself.

The Heath is only 2,000-5,500 feet deep, lying below the Tyler Sand. Horizontal drilling, according to Beiter, not only allows contact with more of the reservoir, but also is an avenue to connect beds and natural fracturing.

One of the challenges to the play, Beiter continues, is the lack of service infrastructure in the area as it moves into a more of a development mode. He says his company began by experimenting with an approximately one-to-one ratio of lateral length to vertical depth.

“Whether that figure holds is still up in the air,” Beiter adds, noting the Heath Shale is mostly an oil play with a low ratio of associated gas.

He says companies still are evaluating production numbers to determine what works and what the decline curves of the wells will be. Because of that, Beiter says there is no way to gauge how many wells CMR will drill in 2013.

“As these new plays emerge, you think you have the solution, and then the formation has something else in mind,” he muses. “We have seen a little of that. Our work has been very technically driven. It is a big investment, and you have to spend the time and effort to understand the formation and find the most economically efficient method to produce it. We have to have more data.

You would like to have it come quicker,” Beiter concludes, “but like they say, ‘No wine before its time.’”

Regional Geology

Peter Dea, president and CEO of Denver-based Cirque Resources, says his company’s strategy is to build, create value and sell, which it first did in the Bakken Shale. It began leasing acreage in the Heath Shale in 2008. He says Cirque plans to employ the same strategy in the Heath: come into the play, bring in a partner, establish production, and then sell.

“We latched on to the play because Senior Geologist Rich Bottjer did good regional exploration geology,” Dea explains. “We were mindful of this being similar age rock to the Bakken, and that it sat in an historical petroleum system that had produced nearly 150 million barrels in the Tyler and Cat Creek sands, mostly sourced from the Heath Shale. In fact, in the early 1980s, the Montana Bureau of Mining looked at mining the Heath Shale where it outcropped. That never became feasible, but the data showed how rich it was.”

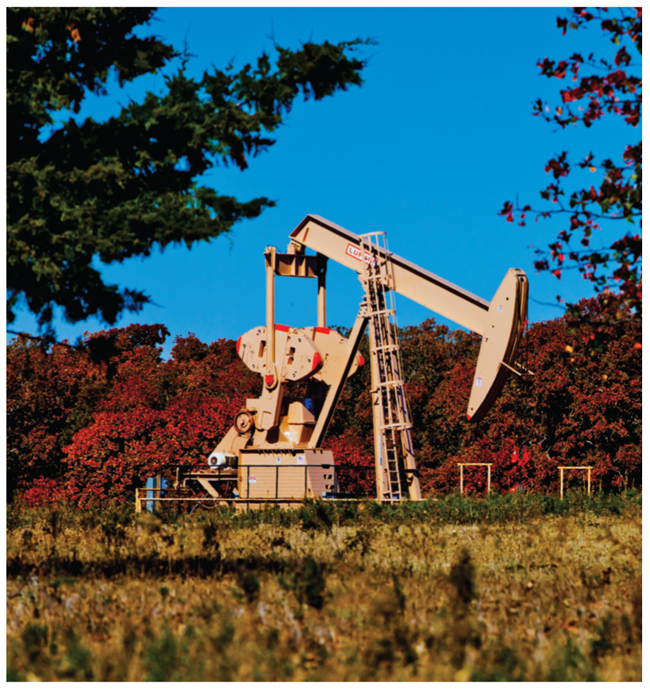

Cirque Resources drilled its Heath Shale discovery well in Central Montana, the Rock Happy 33-3H-2, in November 2011. President and Chief Executive Officer Peter Dea says the company’s strategy is to build, create value and sell.

Dea says Cirque’s discovery well, the Rock Happy 33-3H-2, was drilled in November 2011 and made 271 barrels of oil a day. The following March, Fidelity E&P drilled the Schmidt 344-27H eight miles away, which made 249 bbl/d over its first 25 days.

Cirque hasn’t drill another well since its discovery, but that will change, Dea says. “We are shooting a small 3-D seismic in four areas to delineate our drilling locations for 2013,” he reported in December. “We shoot 3-D seismic for defense and offense, to stay away from faults and to guide our geosteering.”

He says his company plans to drill two or three wells this year with expected depths of 4,000-6,000 feet and lateral lengths of 4,000-5,000 feet with 15-19 frac stages. Targeted costs are $3.5 million-$4.0 million a well, according to Dea.

Although the decline curve for Heath Shale wells has yet to be determined, he says he expects them to have EURs of 200,000-300,000 boe.

“It is remarkable, however, as you climb the learning curve how EUR and rates go up and costs go down over time in these new plays,” Dea ponders. “We control 100,000 acres in the main block–primarily in Rosebud and Musselshell counties. The Heath Shale has a 400-foot oil saturation, so there is a lot of oil in place.”

Smackover/Brown Dense

One of the newest tight oil plays is the Smackover/Brown Dense formation in southern Arkansas and northern Louisiana. This play has mostly flown under the radar thus far.

“It is very much in the early stage,” offers Don Briggs, president of the Louisiana Oil & Gas Association. “Companies are still testing, trying to figure it out. These are 8,000- to 11,000-foot wells and they are drilling laterals, but there isn’t a lot of information available yet.”

Southwestern Energy Co. and Cabot Oil and Gas Corp. are the leading exploration companies in the play, according to Briggs. Southwestern has approximately 540,000 acres and Cabot has 13,600 acres targeting the Lower Smackover/Brown Dense formation.

In its third-quarter earnings teleconference call, Southwestern Chief Operating Officer Billy Way announced his company had drilled and completed six wells in the play. Way says the fourth and fifth wells were drilled as vertical tests to see whether they would encounter the same high pressure the company saw in its third well, the BML. He points out that both vertical tests did encounter the same high pressure.

“We tried several fracture stimulation recipes in our fourth well, primarily involving different combinations of linear gel,” he explained in the conference call. “In our fifth well, we completed three vertical stages totaling 12 feet of preparations with white sand and slick water in the sand stages. Production from this well stabilized at approximately 200 bbl/d (oil) and 1.2 million cubic feet of gas for 10 days. We are using these wells to obtain additional log data and core samples, and to study the effectiveness of different fracture stimulation treatments on the contact area to learn more about fracture height growth.”

Way says Southwestern expects to drill laterals in the wells some time in 2013.

“Southwestern’s sixth well, the Doles, located in Union Parish, La., was drilled in September to a vertical depth of 10,673 feet with a 4,700-foot completed horizontal lateral,” he adds.

Way notes that Southwestern expected to begin selling both oil and gas from the Doles and BML wells with the expectation of learning more about their decline characteristics before year-end.

With the Haynesville Shale natural gas play and the emerging Tuscaloosa Marine and Smackover/Brown Dense oil plays, these are exciting times in Louisiana, according to Briggs. “But as I point out to our regulatory agencies, we are competing with all these other new plays around the country,” he hedges. “These companies have options for where to spend their money. We have to be competitive.”

Stealth Play

Bud Brigham, who was CEO of Brigham Exploration before it was sold to Statoil late in 2011, has a unique perspective on the new oil resource plays. He was one of the early pioneers in the Bakken Shale and has watched closely the emerging plays that have followed.

“It is really interesting,” he says. “Natural gas took off in the early to mid-2000s with horizontal drilling and multistage hydraulic fracturing. But there was a lot of doubt whether you could do that with oil. We scouted the country and landed in the Bakken and the Mowry in the Powder River Basin. We were not able to crack the code in the Mowry.”

The Bakken, on the other hand, has become one of the industry’s greatest success stories.

“Although the early wells in a new play may be disappointing, you have to continue leveraging the evolving technology and innovating to, hopefully, develop an optimal recipe for plumbing the oil out of the ground,” Brigham describes.

After selling his company, Brigham is starting over with Brigham Resources in Austin, Tx. “We plan to invest in four to five resource plays,” he reports. “We are optimistic that with a portfolio, several will work. One of these is a stealth play that is largely not on the radar screen and has not had any horizontal wells drilled yet. It is, therefore, higher risk, but we believe we have the knowledge and expertise to lower the risk and hopefully delineate attractive economics.”

Brigham says his new company has more than 20,000 acres in its stealth play, which he declined to identify, and plans to do some initial drilling in it this year.

“We believe we are in the early innings and that technology will continue to evolve to improve our ability exploit tight oil plays,” he evaluates. “All of this is so beneficial for our country in terms of trade balance, national security, jobs and the economy. It is a great time to be in this business with the expertise we have to find and develop these potentially vast new oil fields.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.