U.S. Natural Gas Industry Positioned For Dominant Role In Global LNG Markets

By Andrew D. Weissman

WASHINGTON–The debate over the extent of U.S. liquefied natural gas exports brewing in Washington has far-reaching implications for the upstream oil and gas industry, and the country. It is vital for every producer to understand why the stakes are so high and the work that needs to be done to maximize opportunities for the industry.

It is clear that LNG exports represent the next big breakthrough opportunity for the U.S. natural gas industry. This article explores in depth the size of the potential market for U.S. LNG exports and clamors for the evidence that can be marshaled to support the industry’s position. It concludes that the industry can and should develop a compelling set of facts to “blow the opposition out of the water” to an extent that has not yet occurred.

By telling the industry’s story more effectively, producers can demonstrate convincingly that the United States can simultaneously ramp up LNG exports at a rapid rate while fully satisfying a host of other emerging market needs, with only a minimal impact on energy prices in the domestic market.

The sooner this evidence is assembled, the more likely it is that the natural gas industry can rebound decisively, and reap more fully the benefits of the historic breakthroughs in natural gas development it has achieved over the past few years.

Unparalleled Opportunity

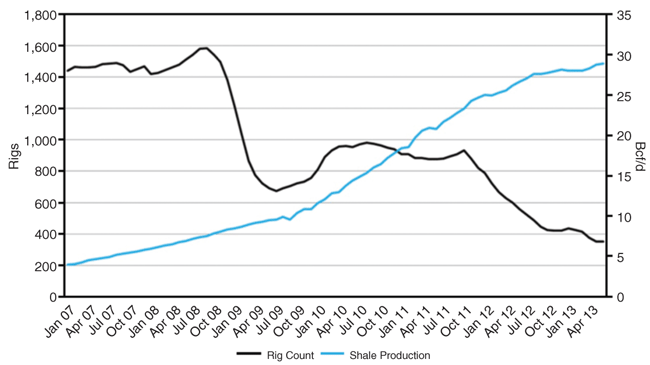

As the techniques for shale development have improved, growth in U.S. production has outpaced growth in core U.S. demand, even with a 70 percent reduction in the number of rigs drilling for natural gas over the past five years (Figure 1).

As a result, for more than two years, prices in the day-ahead market at Henry Hub have traded under a $4.50/Mcf ceiling, well below fully loaded break-even costs for many producers. Furthermore, the futures market does not expect this to change anytime soon.

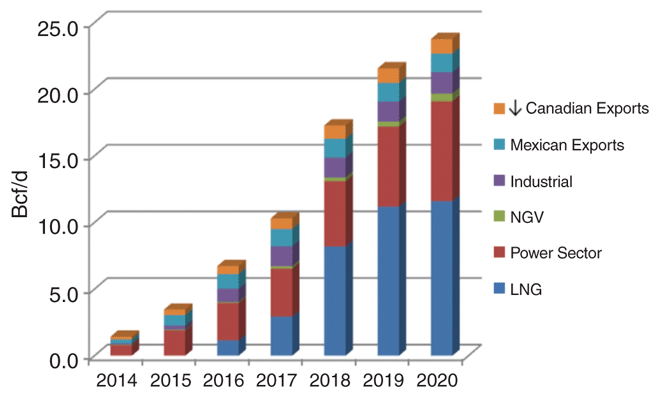

FIGURE 2

Cumulative Increase in Demand by Source

For U.S. Production (2014-20)

Source: EBW Analytics

Over the past few months, however, a light has finally emerged at the end of the tunnel. The United States, once the world’s largest importer of energy resources, is now poised to become the largest LNG exporter in the world. If this unparalleled opportunity is captured, it could trigger five to seven years of unprecedented growth in demand for domestic natural gas, with the potential of an increase of as much as 20 billion-25 billion cubic feet a day by the end of the decade (Figure 2).

This potential for previously unimaginable growth creates a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for every U.S. producer that controls attractive reserves, raising asset values sharply, and simultaneously providing a huge boost for the service industry. But this opportunity is unlikely to be fully realized unless the industry demonstrates in a powerful manner that the market can absorb increases in demand of this magnitude with only moderate increases in prices for natural gas.

That is why it is so vital for the natural gas production sector to seize the initiative by forcefully making the case for LNG exports. The key is demonstrating that the supply-side revolution enabled by shale gas plays can provide in abundance the resources to meet any and all future U.S. demand growth scenarios while simultaneously anchoring a vital new source of revenue creation and job growth for the nation’s economy.

Dominating Position

As recently as the end of last year, the conventional wisdom was that the market for U.S. LNG exports was likely to be small, most likely no more than 4 Bcf/d-6 Bcf/d. Over the past few months, however, it has become clear that this view is plainly false. Rather than the nation being a secondary player in the world’s growing LNG market, exporters from stateside terminals are in a position to dominate the global market for new supplies–providing the federal government acts expeditiously in finalizing required regulatory approvals.

It has become clear that global demand for LNG is likely to grow far more rapidly than previously expected. A year ago, most LNG market specialists were predicting that global demand would grow at a moderate pace. Most studies focused principally on the three largest traditional sources of demand (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan), where demand growth was expected to be relatively flat, especially after Japanese nuclear units were brought back on line in the aftermath of the 2011 accident at Fukushima.

Indonesia and Malaysia were expected to remain major exporters. India was expected to rely principally on domestic sources of supply. Furthermore, potential emerging sources of demand in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa often were ignored or at least downplayed. While significant growth was expected in Chinese demand for LNG, many estimates were significantly lower than they are now.

All of this has changed–and it has changed rapidly and radically. Confidence that Japan will be able to restart a high percentage of its nuclear fleet has started to fade, increasing the likelihood that Japanese LNG imports will grow substantially. India has made a huge stride into the global market, and carries the potential that purchases will continue to surge.

On the supply side, LNG export projects in Indonesia and Malaysia have experienced steep declines, and both countries are now expected to instead become major LNG importers. In addition, new sources of demand have emerged all over the globe, including in countries that were not previously expected to import LNG, such as South Africa and Uruguay. Some estimates indicate that LNG demand from Thailand and Vietnam alone could grow by as much as 900 million cubic feet a day every year for the rest of the decade. Several countries in the Middle East also could become significant importers.

Chinese Demand Growth

The most important source of increased demand, however, is China. While Chinese LNG imports have long been anticipated to grow, estimates of future Chinese demand have soared, thanks in part to strong political pressure that has developed to address intolerable levels of air pollution resulting from China’s high dependence on coal. The Chinese government’s most recent five-year plan calls for adding a major new natural gas-fired combined cycle plant every six weeks for the indefinite future, in addition to converting 3.5 million residential users each year from heating oil to natural gas.

As a result of the incremental demand created by these projects, Chinese demand for natural gas is expected to grow by 25 Bcf/d through 2020. The Chinese government’s plans call for 20 percent of this increase to come from growth in LNG imports, representing an increase of 5 Bcf/d over 2012 levels.

The expected future use of LNG is rising rapidly in nearly every region of the world. In response, estimates of global demand have been escalating sharply. Shell, for example, estimates that global LNG demand could more than double from 31 Bcf/d in 2012 to 65 Bcf/d by 2025 (10 Bcf/d or more above many estimates published only last year). Some forecasters are predicting that demand could rise even more quickly, including FACTS Consulting (a highly regarded consultancy headquartered in London), which predicts that demand could rise to 74 Bcf/d, and ICF International, which projects 68 Bcf/d at the high end of the range.

While 2025 may seem distant, given the seven- to 10-year lead times required to design, permit, finance and construct a major LNG export project, the window to move forward with projects to meet this potential demand will start to close soon. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that over the past year, nearly every one of the supermajors has made massive commitments to invest in new projects, principally in the United States.

There is substantial reason to believe, however, that growth in demand over the next seven to 10 years will be even greater than recent estimates suggest, particularly in China. An additional increase of 5 Bcf/d-10 Bcf/d over and above the estimates cited would not be surprising.

Fanciful Notion

China remains critical. The projected 5 Bcf/d increase in Chinese LNG demand already accounts for 10-15 percent of the potential increase in global demand. The Chinese government’s plan, however, calls for most of China’s incremental needs to be met by spectacular growth in Chinese production of natural gas from new shale development.

While the characteristics and likely development costs for Chinese shale plays are not yet well understood, it is possible (perhaps even likely) that China will strive to meet a significant portion of its needs from domestic supplies over the longer term. But the notion that China will be able to begin to immediately ramp up production quickly enough to meet the Chinese government’s targets is fanciful. To reach domestic supply targets, China would need to increase production from coalbed methane and shale at unprecedented growth rates (61 percent for CBM and an even steeper 78 percent from shale, the primary source of expected new supply).

Few, if any, reputable experts believe that China can achieve these heroic goals–or even come close. To date, efforts to develop natural gas from CBM in China (a much simpler process than developing natural gas from shale) have been extremely disappointing, with at least one major Chinese producer abandoning CBM entirely.

If anything, the likelihood of China expanding shale production at the rate required to meet the government’s goals is even smaller. To date, only a small number of wells have been drilled in shale formations using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, at costs several times greater than development costs for U.S. shale plays.

Furthermore, China also lacks nearly every resource required to achieve the growth rates being targeted, including an in-depth assessment of the characteristics of different reserves, state-of-the-art equipment, pipeline infrastructure, a large and highly skilled service industry, and water resources.

These impediments eventually will be overcome. Even if the required data and physical infrastructure were already in place–and they most definitely are not–“cracking the code” for shale is more an art than a mechanical process that can be readily replicated, and each individual play comes with a steep learning curve. Realistically, therefore, it is likely to take years before China can start to achieve growth rates comparable to the forecast yearly increases in domestic demand. Even then, the development costs could still remain at a multiple of U.S. levels.

Political Pressure

The likelihood is that growth in Chinese demand will be much greater than the goals set in the government’s most recent plan. Over the past year, Chinese citizens have become increasingly enraged at deadly air pollution in many Chinese cities. This violent reaction was further inflamed by a National Science Academy study, co-authored by a Chinese scientist, that estimated pollution from coal-fired plants caused 450,000-550,000 premature deaths each year in northern China, and greatly increased respiratory illness and seriously compromised quality of life on a daily basis for a large portion of the population.

The political pressure this is creating on the Chinese government is intense and it is growing–and has started to impose a major threat to the ability of the Chinese government to retain its power.

In response, the Chinese State Council announced in September that it was banning the construction of new coal-fired plants in three key industrial regions, including areas that surround three of its most important population centers: Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The impact of this ban is not included in any of the gas demand estimates.

Over the next few years, there is a high likelihood that additional measures will be adopted to restrict the use of coal, leading to further increases in Chinese demand for natural gas, much of which can be met only by aggressively increasing LNG imports. This will be particularly true if extreme weather events and the shift in U.S. policy regarding climate change increase the pressure on China to cap emissions of greenhouse gases.

The warning signs are clear. Viewed realistically, there is a high probability–perhaps even a near certainty–that for at least a decade, Chinese demand for LNG will be much greater than nearly every forecaster assumes.

Off The Mark

Many forecasters acknowledge that a 5 Bcf/d estimate might prove to be “conservative.” Implicitly, using a conservative estimate is considered to be a virtue. Conservative estimates of demand, however, can lead to estimates of the global supply/demand balance that are far off the mark. Since energy markets are exquisitely sensitive to even small shifts in the supply/demand balance, this in turn, can set the stage for severe price spikes.

For LNG, where the lead times for new projects can be as long as 10 years, these imbalances could persist for many years, with a potentially devastating impact on the economies of LNG-importing countries outbid by countries with several trillion dollars of liquid reserves.

By the later part of the decade, therefore, there is reason to fear that massive year-over-year increases in Chinese LNG imports will drive global prices through the roof. This could have a potentially crippling effect on the global economy, similar to what occurred in the global oil market in 2008, when runaway increases in Chinese demand played a major role in driving oil prices to nearly $150 a barrel.

While this is not the only major shift in the global supply/demand balance that has occurred during the past year, the likelihood that global LNG demand will be at or above the high end of recent projections is great.

At the same time that potential demand has been escalating sharply, many expected sources of supply have been collapsing. As recently as the beginning of this year, many LNG market specialists were predicting that the market would be oversupplied for many years. This assessment was based in substantial part on plans to construct more than 50 new LNG liquefaction trains.

If construction of all of these projects had gone forward, Australian exports would have been poised to grow from 2.7 Bcf/d in 2012 to as much as 20.0 Bcf/d by early in the next decade–nearly a 10-fold increase–making Australia by far the largest LNG supplier in the world. In addition, new green-field projects were expected to be built in several other parts of the world, including Indonesia and Malaysia, along with new liquefaction facilities in Nigeria and Angola, and expanded production in Qatar.

Over the past few months, however, this picture also has been completely redrawn. Several factors have been involved. These include:

- Runaway costs for constructing new green-field projects;

- Massive increases in natural gas production costs in Australia and other countries;

- More rapid than expected declines in reserves, particularly in Indonesia and Malaysia (until now, key sources of supply for the Asian market); and

- A general recognition that, as a result of these cost increases, most proposed green-field projects are unlikely to be able to cost-effectively compete with brownfield projects built at the sites of existing LNG import terminals in the United States.

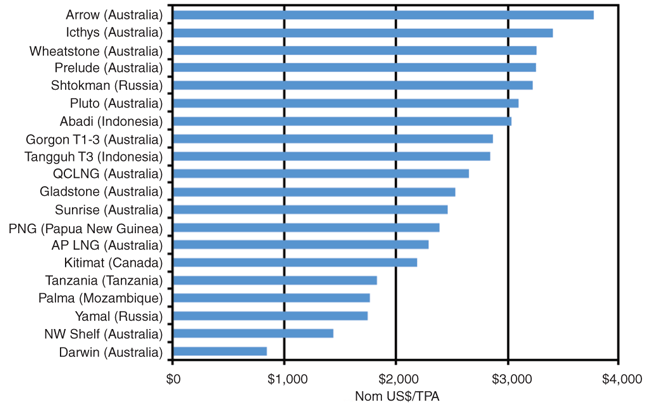

The implications for Australian projects are particularly significant. Until recently, Australia was expected to be the lynchpin of future global supplies–the same role Qatar played in the past decade, but on steroids. Currently, seven projects are under way in Australia, with the potential to add 8.1 Bcf/d of new supply. The likelihood is that most of these projects will be completed, helping to stabilize the global market for a brief period. The costs for these projects, however, have reached astronomical levels (as high as $3,000 a U.S. ton each year). In a heartbeat, Australia has gone from one of the world’s lowest-cost LNG suppliers to one of the highest.

As a result, most Australian projects are no longer competitive in the global market. A study by McKinnsey, for example, concluded that, even after taking into account the higher shipping costs to move LNG from the United States to Asia, LNG supplies from green-field projects in Australia are likely to be 30 percent more expensive than from brownfield projects in the United States.

Few, if any, $10 billion+ projects are likely to be built when the developers know in advance that the projects are not likely to be competitive in the global market. While most of the pending Australian projects have not been cancelled yet, nearly every Australian project that has not yet broken ground is on indefinite hold. The likelihood that these projects will go forward soon is very low, and many may never be built, creating a huge gap in expected global supply.

Developments in Australia, however, are being repeated elsewhere around the globe (Figure 3). As a result, except for the projects in Australia, only two green-field projects are under construction anywhere in the world.

By contrast, as work has continued on proposed U.S. projects, it is becoming increasingly clear that brownfield conversion projects at the sites of lower-48 import terminals are among the most attractive (and lowest cost) sources of supply. Until recently, it was not clear whether the United States would become a major LNG exporter. Prior to last year, only a handful of applications for export authorization had been filed with the U.S. Department of Energy, and final authorization for the first U.S. project (trains 1-4 of Cheniere’s Sabine Pass project in Louisiana) was not issued until January 2013.

Furthermore, many questioned whether U.S. projects were economically viable, based on earlier forecasts of domestic prices for natural gas and the need to ship LNG over much longer distances. It also was unclear how quickly DOE would act on pending applications for export authorization, or whether U.S. projects could be successfully financed.

Over the past year, however, nearly all of these doubts have been obliterated. This is partially because of the steep decline that has occurred in projected U.S. prices for natural gas, which offsets higher shipping costs for U.S. LNG export projects. It also stems from the ability to achieve major cost savings by using docking facilities and storage tanks at U.S. terminals built to land LNG imports, greatly reducing the necessary capital.

It has become increasingly clear that U.S. projects enjoy a long list of other compelling advantages from the standpoint of potential purchasers. These include the ability to tap the largest and most liquid natural gas market in the world, the most extensive pipeline infrastructure, and a huge and experienced work force in the Gulf.

They also include the ability to utilize many of the best engineering, procurement and construction contractors in the world right on their home turf; greatly reduced project completion risk; reduced political stability risks, compared with many other countries; and the lowest currency risks of any country.

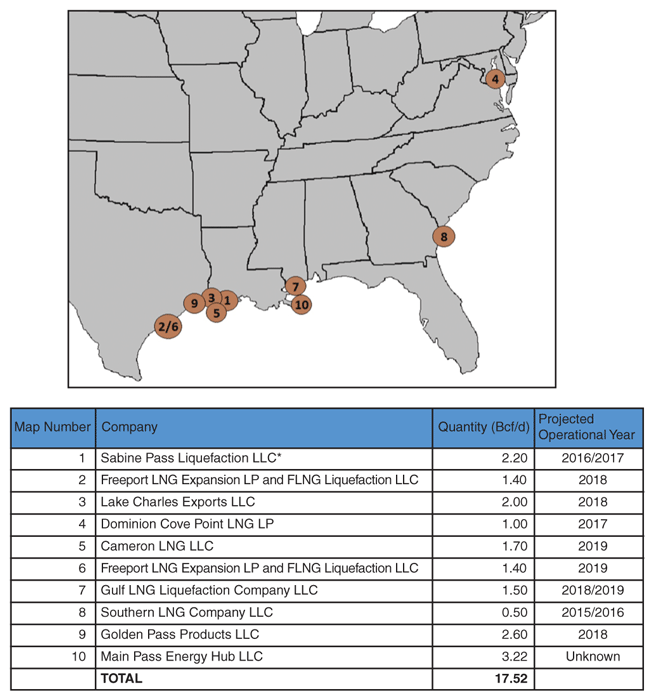

FIGURE 4

U.S. Brownfield Plants with Applications For LNG Export Authorization

Source: DOE, FERC and EBW Analytic

Furthermore, as the Sabine Pass project has demonstrated, given these conditions, by using a project finance model, U.S. developers can raise all of the required capital quickly and at very low cost.

Under these circumstances, given both the limited number of other choices available, and the compelling advantages of U.S. projects, it is hardly surprising that buyers have been flooding into the U.S. market in recent months. In total, firm agreements have been signed by 15 purchasers covering more than 12 Bcf/d of total supply. In addition, many other potential buyers are actively exploring potential purchases from U.S. suppliers, with the likelihood that several more long-term off-take agreements will be signed this year, with additional contracts in 2014.

The “facts on the ground” conclusively demonstrate, therefore, that the potential market for U.S. exports is much larger than many have asserted. The United States, of course, is not the only potential source of new supply. Over time, there is a substantial likelihood that projects will be built in British Columbia, East Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, and there have been some indications that another project will be built in Russia.

Nearly all of these projects, however, are at a much earlier stage of development than most U.S. projects and/or have many difficult (and, in some instances, potentially insurmountable) hurdles to overcome. Moreover, because these are green-field projects, and often require developing new natural gas supply sources in remote locations, the cost structures for these projects tend to be much higher. As a result, the project developers have made it clear that they have no intention of moving forward unless they are able to obtain long-term commitments for pricing indexed to oil, which could far exceed U.S. prices.

By contrast, more than 30 Bcf/d of potential export projects have been announced in the United States, many of which are at brownfield sites and could be completed before the end of the decade, if required federal approvals are granted on a timely basis. Figure 4 shows the locations and initial capacities of brownfield plants that have applied for LNG export authorization as of March 2013.

At least for the next 5-10 years, U.S. projects are positioned to dominate the global market for new supplies–again, if the U.S. government acts in a timely manner–and capture as much market share as the speed of the federal permitting process allows.

Moving forward on these proposed projects can yield tremendous national benefits. Economically, the ICF International study prepared for the American Petroleum Institute–the best analytical work done to date on the potential for LNG exports–found that 16 Bcf/d of LNG exports might result in creating 73,000-450,000 jobs, adding $15.6 billion-$73.6 billion annually to the nation’s gross domestic product.

From a geopolitical standpoint, the benefits could be even more strategic. LNG could play a pivotal role in helping bolster relations with allies seeking low-cost natural gas and wishing to diversify the security of their energy supplies. At the same time, LNG could reduce the effect of economic weapons consistently wielded by many diplomatic foes.

Environmentally, the role of natural gas in providing an economically feasible alternative to the harmful emissions associated with coal could play a significant role in reducing global GHG emissions. At the same time, the health benefits from using LNG to minimize local airborne pollutants can help maintain the health and economic productivity of individuals in many developing countries.

While the DOE has granted conditional approval of 6.37 Bcf/d of LNG exports to non-Free Trade Agreement (FTA) countries, many more projects remain sidelined by regulatory inaction. Only one project, Sabine Pass, has obtained all necessary government authorizations. Although applications for FTA countries receive almost immediate approval, pending applications for LNG exports to non-FTA countries are those that can unlock the greatest economic, geopolitical and environmental benefits.

Even after receiving the DOE’s conditional approval for LNG export to non-FTA countries, proposed projects must receive Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approval for siting, construction and environmental review. At this stage of the process, the opportunity exists for adverse parties to intervene and litigate any approval, with challenges likely based on the cumulative impact of LNG exports on the environment and concerns over the domestic price of natural gas.

After obtaining the necessary certification from FERC, however, projects must once again traverse the DOE for final approval, which opens the opportunity for yet another set of legal proceedings by adverse parties.

Not only is the repetition embedded in the regulatory framework cause for uncertain timing and delays, the repeated potential for legal challenge opens the door for careful scrutiny of the process. The DOE has assessed the effects of large-scale LNG exports based on two studies commissioned in 2012 that use data and projections from an even earlier time frame. The Energy Information Administration likely will issue the early release of its Annual Energy Outlook for 2014 sometime this fall, and DOE Secretary Ernest Moniz has stated publicly that he will take the conclusions into account.

The EIA’s early release of the 2014 Outlook likely will revise natural gas reserves significantly higher, possibly reducing future prices. On the other hand, however, many parties have clamored for the “reference case” to more fully account for other sources of increased demand, and forecast prices may increase as a result. In its 2013 Outlook, the EIA went out of its way to note that “the cost of developing new incremental production needed to support continued growth in natural gas consumption and exports rises…”

The EIA’s trepidation is not completely unfounded. And since the publication of the 2013 report, the potential for enormous growth in non-LNG demand for natural gas has become even more apparent. Growth in exports to Mexico, power sector demand stemming from coal plant retirements, the industrial renaissance along the Gulf of Mexico, and the potential for more widespread adoption of natural gas vehicles all may serve to boost anticipated demand for natural gas.

In particular, President Obama’s Climate Action Plan appears likely to accelerate coal plant retirements and shift an even larger share of power generation to natural gas-fired capacity additions.

To date, there has been only a muted discussion that demand could grow this rapidly. As noted in Figure 1, under very plausible scenarios, natural gas demand could increase 20 Bcf-25 Bcf/d by the end of the decade. There is considerable question that supply can grow quickly enough to limit increases in price to acceptable levels.

Even if not under consideration for the first tranche of LNG export approvals, these issues are sure to emerge into the limelight as subsequent projects must pass muster against the cumulative projected increases in demand. Although highlighted mainly by industrial users so far, the issue of cumulative demand increases will be of critical concern to utilities planning resource adequacy around coal retirements, the ability of natural gas to be both a clean and economic substitute to coal for environmentalists, and a potential risk against the widespread adoption of NGVs.

From the industry’s point of view, it is critical not only that LNG exports occur, but that these other sources of demand develop as well. The shale resources are of such enormous dimensions, and advances along the learning curve are occurring at such a rate, that failing to achieve full development of demand may result in lagging natural gas prices for the foreseeable future.

Therefore, it is to the industry’s benefit to not only assert, but to demonstrate conclusively, that increases in demand can be met in a timely and cost-effective manner. The shale revolution is continuing to evolve, with the shift to pad drilling, increasing reserves, decreasing drilling times, increasing lateral lengths, increasing frac stages, tighter well and lateral spacing, better fracturing and completion techniques all providing testament to the ability to rapidly expand production.

Even more, these developments appear likely to continue to improve. New targets hold enormous potential, with some comparing the Utica Shale to the Marcellus and the Bossier Shale to the Haynesville. Reserves to target may continue to grow, and drilling costs may continue to decline.

To outsiders, however, these developments are not readily apparent. It is absolutely critical for the industry to pull together data on these developments, basin by basin, and press the information advantage to leave no doubt as to the ability to rapidly increase supply to meet enormous demand increases. Policymakers and the public must be convinced that the resource dimensions and cost effectiveness of natural gas can be accomplished with appropriate planning.

From a policy perspective, no systematic national planning has occurred on an integrated basis. Many changes are likely necessary to federal procedures to more quickly enable the build-out of this critical pipeline infrastructure. In the private sector, large users of natural gas may be encouraged to enter into long-term supply contracts and joint venture agreements to further ensure the market has adequate time to meet demand increases.

Although some may seem superfluous now, these developments are absolutely essential to navigating the inevitable pitfalls along the path to fully realizing the enormous opportunity now before the U.S. natural gas industry.

ANDREW D. WEISSMAN is senior energy adviser at Haynes and Boone LLP, and chief executive officer and founder of EBW Analytics Group, an energy market analysis service. During his 35-year career, Weissman has provided strategic advice and counseling to independent oil and gas producers, power producers, major electric and gas utilities, hedge funds and energy traders, retail and wholesale energy marketers, equipment vendors and large energy users, typically at the CEO level. He also has played a key role in developing innovative new business structures and in helping to transform energy and environmental policy at the state and federal levels. Weissman helped pioneer the use of emissions trading in the United States, structuring nearly all of the early transactions, and has been actively involved in the effort to replace coal-fired electric generation with natural gas-fired generation.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.