Northeast Activity Profile

Vast Resource Potential Has Operators Gearing Up To Test Utica Shale Formation

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

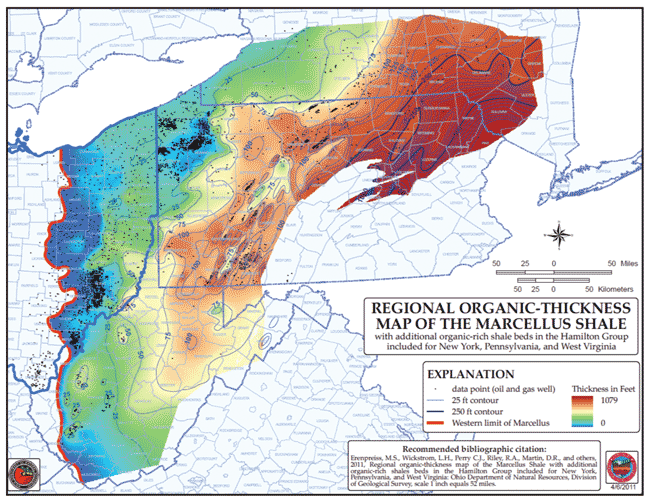

The Marcellus Shale is a thick “blanket” formation that covers 95,000 square miles (61 million acres) across the Appalachian Basin. Seven years after Range Resources drilled the discovery well to the play, the Marcellus ranks as the second largest natural gas accumulation on the planet, with up to 500 trillion cubic feet of estimated recoverable reserves.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, natural gas production in Pennsylvania and West Virginia now averages almost 4 billion cubic feet a day–more than five times the average daily volumes produced in the first four years of Marcellus activity from 2004 to 2008–and accounts for more than 85 percent of all gas produced in the Northeast United States.

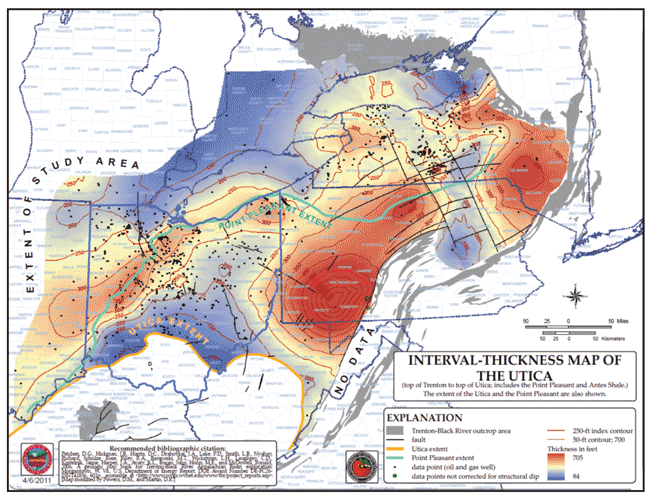

But lurking 2,000 to 7,000 feet beneath the massive Marcellus formation is an even more dominant geologic feature: the Utica Shale, an Ordovician-age formation that is thicker and much more geographically expansive than even the Marcellus.

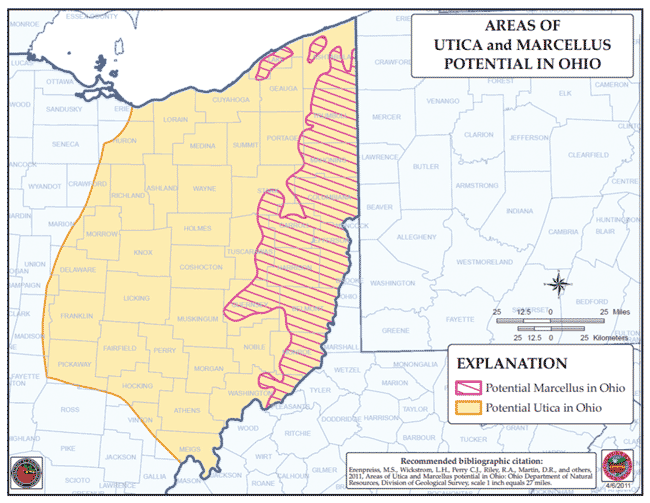

In fact, the Utica has nearly twice as much areal extent as the Marcellus, spanning more than 170,000 square miles (110 million acres) beneath eight states and across the border into Canada. The epicenter of initial drilling and development activity to test the potential of the Utica is in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania.

Similar to the local economic booms associated with the Marcellus in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, the Bakken Shale in North Dakota and the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas, leasing and initial exploration and drilling activity already are generating economic benefits in Ohio, one of the states hit hardest by the recession and chronic high unemployment rates. Just how significant could Utica activity be for the Buckeye State’s economic recovery?

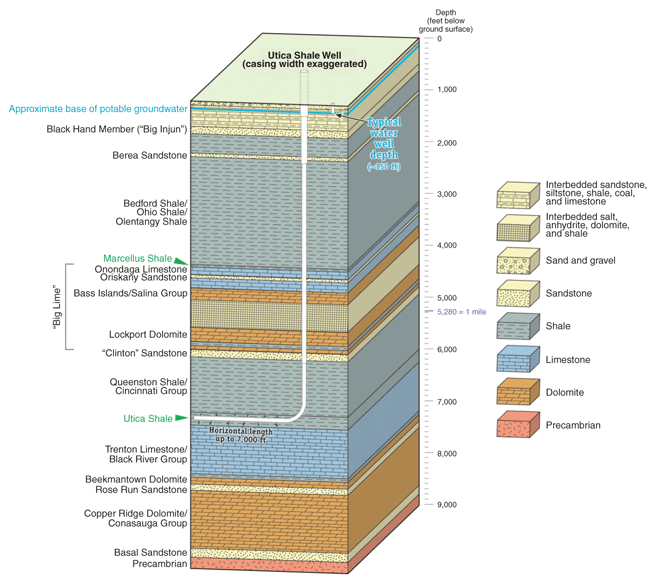

Growing numbers of oil and gas companies are gearing to test the liquids-rich Utica Shale below the Marcellus formation in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Thanks to the Marcellus play, rigs capable of drilling long-lateral horizontal wells, frac crews, production infrastructure and other services and equipment are already largely in place to support Utica development. Shown here is the generalized geology and profile of a prototype Utica Shale horizontal well in east central Ohio.

‘Our Economic Recovery’

A report prepared by Kleinhenz & Associates for the Ohio Oil & Gas Energy Education Program estimates more than 204,000 jobs will be created or directly supported by Utica Shale leasing, exploration, drilling and pipeline construction over the next four years. That number equates to 40 percent of the total number of state residents that were classified as unemployed in September!

Moreover, oil and gas producers are projected to invest $34 billion in the state by 2015–including $12 billion in wages–with local government wage tax revenues amounting to $240 million in 2015, excluding severance or ad valorem taxes.

Not surprisingly, observers in Ohio and other Northeastern states have taken to calling the emerging Utica Shale play, combined with ongoing Marcellus development, “our economic recovery.”

“The Utica is our opportunity for economic recovery. This is our chance to bring significant investment and job creation to Ohio to drive meaningful long-term growth,” says Larry Wickstrom, state geologist and chief of the Division of Geological Survey at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. “It is happening already.”

Marcellus activity in neighboring Pennsylvania provides an obvious analogue of the kind of positive impact the Utica Shale play could have on the economic situation in Ohio. For example, a study issued by the Pennsylvania Department of Labor & Industry in October reported that Marcellus activity had created 218,000 jobs in the state by the end of 2010, and that Marcellus-related employment doubled between the start of 2008 and the end of 2010–a time frame during which virtually every other industrial sector in Pennsylvania and everywhere else across the country was shedding huge numbers of jobs.

The study also found that core Marcellus jobs paid much higher annual salaries than jobs in other sectors (averaging $76,000 compared with $46,000 for other industries), and that Pennsylvania counties with significant Marcellus drilling had seen notable decreases in unemployment.

In addition, a Pennsylvania State University study illustrates the significant impact Marcellus Shale activity has on job creation in ancillary industries, such as the financial and insurance sectors, where 4,200 new jobs in the state are attributed to Marcellus development activity.

Very Big Play

“We think we have a very big play and it is on the cusp of really taking off in Ohio,” Wickstrom enthuses. “The Utica is an organic-rich shale that we have known was there all along, but it is now a proven development target. The leasing frenzy started in 2010 in Ohio and it continues. It became ‘the next big play’ before anyone even had drilled a well.”

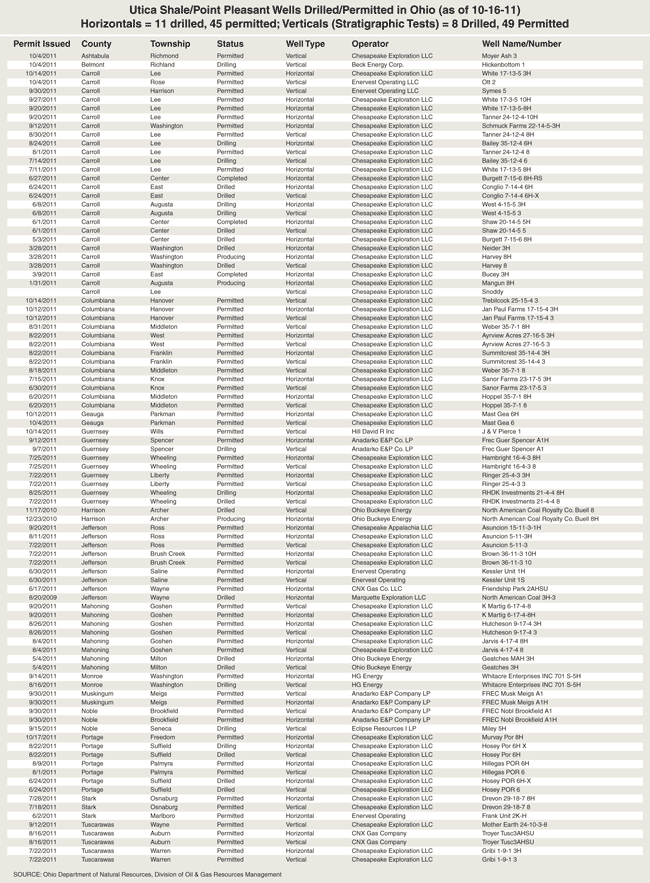

That is changing quickly, however, with operators announcing several successful wells and plans for increased drilling in 2012 by a growing list of oil and gas companies with burgeoning Utica lease positions (Table 1). Wickstrom predicts that the Utica Shale will “take off more rapidly” than the Marcellus did because rigs capable of drilling horizontal wells, frac crews, production infrastructure and other support services are already in place, thanks to booming Marcellus development activity.

“It is a liquids-rich play. It is yet to be seen how big the oil window is. Until information is released, we will not know the economic drivers around Utica development. We need gas processing facilities and fractionation plants in the area,” adds Wickstrom. “But this is a wonderful, huge economic opportunity.

Terry Engelder, a professor of geosciences at Penn State University, emphasizes that the Marcellus and Utica are separate plays. Although the Utica lies below the Marcellus (with several formations between the two), Engelder says that as the Marcellus thins as it moves westward into Ohio, the Utica gets thicker (Figures 1 and 2).

“The Marcellus is about 389 million years old,” Engelder explains. “The Utica is 450 million years old. That is 60 million years of difference when the hydrocarbons were deposited. The tectonics changed during that time to affect how each shale was formed. You always hear that not all shales are the same. It is important to appreciate that when understanding the difference between the Marcellus and the Utica.”

Engelder notes that although there are some areas such as Washington County in southwestern Pennsylvania in which both formations are equally attractive, there are many other areas in the Appalachian Basin where the Marcellus will be the only target, and other areas where only the Utica will be prospective.

“The Marcellus boom has hit in northeastern Pennsylvania and has revitalized a lot of small towns in that part of the state,” he contends. “Marcellus drilling activity will go on for decades. The Utica will extend those wells farther west and revitalize those areas as well for years to come. The industry is looking for an active drilling period of at least two to three decades. The size of the basin and the continuity of the formations add a dimension that is very unusual.”

Point Pleasant Interlay

Figure 3 shows areas in Ohio with potential for Marcellus and Utica development. Wickstrom points out that the Utica ranges from 3,000 to 10,000 feet in depth in the area that is prospective. In Pennsylvania, there are areas in which the Utica is as deep as 14,000 feet. “There are some indications that the formation is ‘overmatured’ at those depths,” he contends.

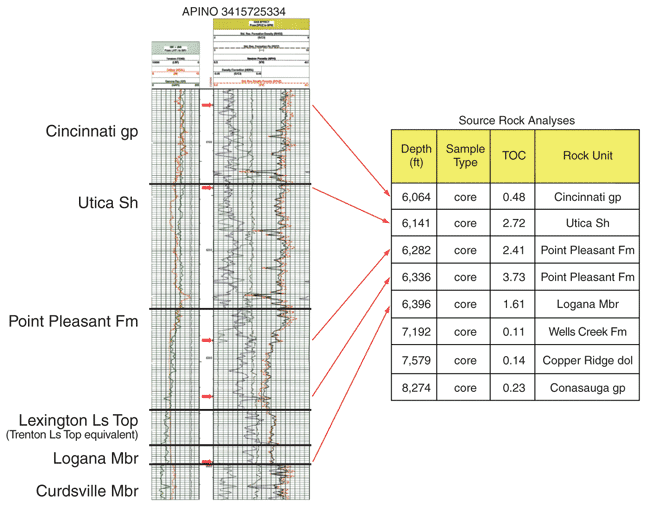

One thing that makes the Utica Shale so attractive as it moves into Ohio is the fact that it overlies the Point Pleasant formation (Figure 4), an interlayered limestone and shale formation that is “actually thicker and higher in total organic content” than the Utica proper, according to Wickstrom.

“It is very unusual,” he says of the Point Pleasant. “It is a black organic-rich crystalline limestone interlayered with black organic-rich shale. The Utica is a wonderful rock, but it is even better with the Point Pleasant beneath it. Since it is interlayered with the Point Pleasant, it is more ‘fracable.’ The Utica in some parts of New York and elsewhere is just the Utica Shale; it does not have the brittleness of the Utica that is interlaid with the Point Pleasant in Ohio.”

Wickstrom says he believes that the Utica/Point Pleasant package covers most of Ohio, western Pennsylvania and the northern parts of West Virginia. “The farther south and east it goes, the more we lose the organic-rich Point Pleasant,” he continues.

Wickstrom says the Utica/Point Pleasant package contains natural gas, liquids-rich gas and crude oil, although he points out that “it is way too early to put any meaningful numbers” on what those percentages will be.

“There seems to be a wet gas window in much of eastern Ohio, and the farther west you go in the state, there is more and more oil,” he offers. “Central Ohio has had good oil production in the past from this interval. The big question is how much pressure there is to get the scale of economics that is needed.”

Wickstrom notes that the design of the horizontal wells and the completion programs likely will differ from the liquids-rich areas to the oil-prone areas.

Working Undercover

Oklahoma City-based Chesapeake Energy Corporation, the second-largest producer of domestic natural gas and a top 15 producer of liquids, holds the leading acreage position in the Marcellus Shale play. The company confirmed market rumors that it had made a major liquids-rich discovery in the Utica Shale in eastern Ohio in July, when Chief Executive Officer Aubrey McClendon spoke during Chesapeake’s second-quarter earnings conference call.

“In some respects, the play reminds us of the Haynesville Shale in that we worked undercover for more than a year to develop the basic geological and petrophysical model,” McClendon said at the time. “We built the largest leasehold position in the play and then drilled the first discovery wells. This is certainly also the case with the Utica, where we started working on the play a year and a half ago, started buying leases shortly thereafter, and today quietly and efficiently have built the largest leasehold position in the play.”

Chesapeake has leased 1.25 million net acres in the Utica play in Ohio in addition to 1.62 million in the Marcellus. On Sept. 28, the company made its first public announcement regarding the results of its initial wells in Ohio. Spokesman Jim Gipson says the company drilled 12 horizontal wells in the discovery phase and “has achieved strong initial production success in the wet gas and dry gas phases of the play from this initial drilling.” He says Chesapeake is early in the process of evaluating the oil phase of the play.

Although eight of the company’s 12 horizontal wells were either being completed or waiting on completion at the time of the announcement, Chesapeake did release the results of its first four completed horizontal wells in the wet and dry gas phases of the play:

- The Buell No. 10-11-5 8H well in Harrison County, Oh., was drilled with a lateral length of 6,418 feet and achieved a daily peak rate of 9.5 million cubic feet of natural gas and 1,425 barrels of natural gas liquids (3,010 barrels a day of oil equivalent).

- The Mangun No. 22-15-5 8H well in Carroll County, Oh., was drilled with a lateral length of 6,231 feet and recorded a peak daily rate of 3.1 MMcf of natural gas and 1,015 barrels of liquids (1,530 boe/d).

- The Neider No. 10-14-5 3H well, also in Carroll County, has a lateral length of 4,152 feet and achieved a daily peak rate of 3.8 MMcf of natural gas and 980 barrels of liquids (1,615 boe/d).

- The Thompson No. 3H well across the state line in Beaver County, Pa., was drilled with a 4,322-foot lateral and had a daily peak rate of 6.4 MMcf of dry natural gas.

The production rates assume maximum ethane recovery, according to Gipson, who says Chesapeake is processing the wet gas stream from the three Ohio wells at a nearby processing facility. He adds that Chesapeake has multiple projects and initiatives under way to process and market future production of NGLs, including ethane.

McClendon agrees with Wickstrom that the Utica appears to have three phases, or windows, similar to the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas: a dry gas phase on the eastern side of the play, a wet gas phase in the middle, and an oil phase on the western side.

“The difference is that we believe the Utica will be economically superior to the Eagle Ford because of the quality of the rock and the location of the asset,” McClendon adds.

Utica Shale Joint Venture

CONSOL Energy Inc. is a long-time Appalachian Basin operator, and has been drilling coalbed methane wells in the region for more than 20 years, according to John Corbett, CONSOL’s district geology manager for southwestern Pennsylvania. He lists the Huron Shale in Virginia, the Chattanooga Shale in eastern Tennessee and the New Albany Shale in Indiana, as well as the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, as plays in which CONSOL Energy is drilling wells.

Harry Schurr, CONSOL’s general manager for Utica operations, says the company is especially active in the Marcellus, working out of three area offices: a West Virginia operations office in Jane Lew, a southwestern Pennsylvania operations office in Waynesburg, and a central Pennsylvania operations office in Indiana, Pa. “All three operations are actively drilling the Marcellus,” he says. “The Marcellus has been our primary focus for the past few years.”

Now CONSOL Energy is adding an active Utica Shale drilling program in Ohio to its portfolio. The company announced on Oct. 24 that it had closed on its previously announced agreement with Hess Corporation to jointly explore and develop CONSOL’s nearly 200,000 Utica Shale acres in Ohio. In the transaction, Hess Corporation acquired a 50 percent interest in the Utica acreage owned by CONSOL for $594 million.

Schurr says CONSOL drilled a vertical well last year in Belmont County, Oh., that generated 1.5 MMcf of gas in 24 hours from Utica Shale, despite the fact that the formation was not stimulated.

“We did not pump any kind of hydraulic fracture treatment on this well,” Schurr notes. “We simply flow tested the Utica on the way through to a deeper target formation.”

Schurr admits, however, that the Utica has been on the company’s radar for some time. “It is not a new play concept,” he remarks. “As companies have drilled vertical wells through the Utica over the years, they have had decent shows and even production from well bores that happened to encounter natural fractures. The question is, will utilizing horizontal techniques make the Utica an economic play?”

First Well Set To Spud

With the Hess joint venture in the Utica, CONSOL is ready to move forward to find the answer to that question, according to Corbett. “We have partnered with Hess, acquired seismic, and expanded our exploratory database,” he states. “We are permitting our exploratory drilling program and are set to spud our first Utica well in November. That well will be in Tuscarawas County, Oh., and is intended to test the pressure as well as the composition of the fluids in the reservoir.”

Because CONSOL and Hess have only begun putting their programs together in the joint venture, Schurr says he does not yet have an estimated number of wells the two companies will drill next year.

“In addition to Ohio, a large part of our southwestern Pennsylvania acreage will have Utica potential,” Corbett adds. “The question is where it is dry gas and where it is wet gas. It looks now like the Utica in much of Pennsylvania is a dry gas play. That is why it has not drawn the same level of attention that it has in Ohio.”

Moving across the West Virginia Panhandle and into Ohio, it appears that the Utica on CONSOL’s acreage becomes increasingly more liquid, producing both liquids-rich gas as well as primarily oil. “We tested the Marcellus in Ohio, but our focus here is definitely on the Utica, where the Marcellus thins and the Utica becomes thicker,” Corbett says.

Schurr points out that CONSOL has a competitive advantage on its Pennsylvania acreage, however. “We have a large legacy acreage position that is either held in fee or by production, so there is no rush to drill the Utica on these leases,” he explains. “That is helpful in terms of planning our strategy.”

Schurr adds that CONSOL has great expectations for Utica development in Ohio. “We believe it will be an exciting play,” he states. “There are a lot of data already reported. There have been a lot of vertical penetrations of the horizon and a lot of historical data where wells have hit natural fractures, so we think we have a good feel for its potential. Now, it is finding the right completion technique to optimize production.”

The development of the Marcellus is acting as a springboard to launch the Utica play, Schurr goes on, noting that high-capacity rigs, plants to process gas, and the knowledge and technology of horizontal drilling and high-pressure hydraulic fracturing are in place in the region to expedite Utica Shale testing and development programs. “This basin was all about the shallow Upper Devonian plays until companies started bringing the first new equipment and technology into the region for the Marcellus play,” he remarks. “Because of the Marcellus, we do not have to start at the beginning in the Utica.”

Pulling Together

With Utica Shale horizontal wells costing as much as $7 million apiece to drill, it is cost-prohibitive for many of the smaller independent operators in Ohio and Pennsylvania to drill their own wells, even though the oil and gas industry has been producing from shallower formations in the region for more than 100 years.

But that is not stopping a group of smaller operators in Monroe County, in the far southeastern corner of Ohio. Koy Whitacre, owner of Whitacre Enterprises in Graysville, Oh., had contact with several companies before making a decision to go with HG Energy. C.F. “Bud” Rousenberg, owner of Profit Energy Company in Jerusalem, Oh., and a group of 15 smaller operators and landowners, subleased approximately 30,000 acres to HG Energy, a Parkersburg, W.V.-based company.

Woodsfield, Oh., attorney Richard A. Yoss has been instrumental from the start of this project by working with HG Energy on behalf of the local producers. Yoss says that in many ways it has turned into a “community project,” and is unlike anything he has seen in his 40 years of practicing oil and gas law.

HG Energy is drilling its first test well for the group on acreage that Whitacre bought 15 years ago and calls “the old Richard Scott property.” The initial well is expected to be hydraulically fractured and tested by the end of November.

“HG Energy initially plans to go vertical through the entire Utica Shale to test it,” Whitacre offers. “The vertical drilling depth should be about 9,500 feet, and the Utica is thought to be about 250 feet thick in this area. If all goes well, HG Energy will put in a cement plug and make the horizontal turn to drill a 6,000-foot lateral through the Utica.”

This is not the first time that the smaller Monroe County operators have united on a project, Whitacre notes. The group went together eight years ago to lay a 65,000-foot, eight-inch pipeline to carry natural gas out of the county. It later sold the pipeline to a large independent.

“We signed a confidentiality agreement, so we cannot disclose the exact terms of our group’s contract with HG Energy, but if the first well comes in successfully, there will be at least 10 wells drilled a year going forward.”

Committed To Drilling

Rousenberg adds, “We decided to go with HG Energy because it was committed to drilling. Some companies will flip the acreage and not do much with it. We had a guarantee with HG Energy that it would drill one well this year and then so many each year after that, if the results were favorable.”

Whitacre, Rousenberg and the other operators in Monroe County have been drilling vertical wells for years in shallow formations such as the Berea, Gordon, Gantz, Thirty Foot and Fifth Sand, all of which are less than 2,500 feet in depth.

“This is a night-and-day difference from what we have been doing,” Whitacre says of the deep horizontal drilling in the Utica formation. “There has never been any horizontal drilling anywhere close around here. It is unreal for this county. We used to drill wells to total depth in only two or three days. HG Energy has built an environmentally safe pad for the drilling operation. It is a totally different ballgame than anything we have seen before.”

Rousenberg says other landowners are forming partnerships in Monroe, Washington, Morgan, Belmont, Noble and Guernsey counties in southeastern Ohio to put together acreage in order to attract larger operators to drill, similar to what the Monroe County group has done. “I know of two or three groups that have put several thousand acres together, but I suspect very few, if any, of those deals involve a drilling commitment such as the group in Monroe County has with HG Energy,” he says, “Everyone is in a waiting mode to see what this well is going to do.”

He says the Utica Shale is providing a much-needed boost to the depressed economy in southeastern Ohio. “The recorder offices in the county courthouses are overrun,” Rousenberg observes. “I have never seen so many land people. I hope HG Energy has good luck. I hope it comes in for them, for us and for everyone else in this area. It has a lot of people genuinely excited, and people around here could use some good news.”

Exciting Time

Fort Worth-based Range Resources Corporation–the company credited with drilling the Marcellus discovery well (the Renz Unit No. 1) in Washington County, Pa., in 2004–drilled the industry’s first commercial Utica and Upper Devonian Shale horizontal wells in southwestern Pennsylvania earlier this year. However, Matt Pitzarella, director of corporate communications and public affairs for Range, says the company is in no hurry to develop the Utica on its extensive regional leasehold.

“That first Utica Shale well in Pennsylvania averaged 4.4 MMcf/d of gas equivalent on a seven-day production test, which is very encouraging,” he states. “But nearly all of our Utica acreage is under our Marcellus acreage and will be held by our more economic Marcellus production, so we will continue to focus on the Marcellus.”

Looking at the potential of the Marcellus, the underlying Utica, and the Upper Devonian formation above the Marcellus, Pitzarella says the combined impact of exploration, drilling, development, production and midstream activity has enormous economic implications for the entire Appalachian region.

“It is a really exciting time in North America. And the great thing is, we are only scratching the surface. Our Marcellus wells are on 1,000-foot spacing and we are expecting to recover 25-30 percent of the resource in place. In the Barnett, which is less productive than the Marcellus with less gas in place, the industry is estimating that recovery percentages are approaching 50 percent, so there is incredible future infill potential,” he enthuses.

“Pennsylvania ranks third in the nation in job increases this year. Washington County, where most of our operations are, has had 5 percent job growth this year, which is the third highest county in the country,” Pitzarella points out. “That makes all of us proud to be creating jobs while producing clean, domestic energy.”

Range has a leasehold of approximately 790,000 acres in the main fairway of the Marcellus, according to Pitzarella, much of which is in southwestern Pennsylvania where the Utica Shale lies below the Marcellus. There is also the Upper Devonian formation above the Marcellus, giving Range multiple drilling targets, most of which have a liquids-rich component to them.

Pitzarella says the base of the Upper Devonian section is approximately 150 feet above the Marcellus at 6,500 feet, and the Utica is closer to 10,000 feet below surface. He notes that Range developed a thorough understanding of the Upper Devonian over the years as it has drilled through the formation on every Marcellus well.

“We may have drilled the first horizontal well in the Utica, but we will allow others to take the lead in developing the play, whereas we did the upfront development work in the Marcellus,” he adds. “We believe our Upper Devonian acreage contains about half the reserves that our Marcellus acreage holds. We have announced 10 Tcf to 14 Tcf of net unproven resource potential in the Upper Devonian. We have not publically disclosed any numbers for the Utica, but it is very exciting. We will continue to drill test wells in the Utica, but nowhere near as many as we plan to drill in the Marcellus and Upper Devonian.”

Multiple Layers Of Wells

Pitzarella says the possibility exists for producers to potentially drill multiple layers of wells in the future, all from the same central pad location. Range announced in October that it drilled 56 wells during the third quarter in the Marcellus and the company’s net daily production from the Marcellus Shale is approximately 350 MMcfe/d net to Range. The division is solidly on track to reach the 2011 year-end production target of 400 MMcfe/d net to Range.

Pitzarella says in Southwest Pennsylvania, Range drilled 42 wells during the third quarter. A total of 28 wells were turned to sales, bringing the total horizontal Marcellus wells producing in the southwest part of the sate to 214. At the end of the third quarter, Range had 12 wells waiting on pipeline and 74 wells waiting on completion in the southwest.

In Northeast Pennsylvania, Range drilled 14 wells during the third quarter, and 10 wells were turned to sales. At quarter’s end, there were 15 wells on production in the northeast region with 11 wells waiting on pipeline and 22 wells waiting on completion, reports Pitzarella.

In its third-quarter operations update, Range announced it had accomplished a key element in developing the liquids-rich Marcellus play by signing its first ethane sales contract with NOVA Chemicals Corporation at the conclusion of the binding open season of the Mariner West Project.

Pitzarella notes that Range also began receiving an incremental NGL pricing uplift late in the third quarter when a C3+ fractionation unit was completed at MarkWest Liberty’s plant near Houston, Pa.–the first processing facility in the state–which was constructed through an exclusive agreement with Range (MarkWest Liberty is a joint venture between MarkWest Energy Partners and The Energy & Minerals Group).

“The complex allows for the production of 60,000 barrels a day of purity propane, butane and natural gasoline for sale into premium Northeast markets,” he says.

With the processing capacity upgrades at the Houston plant, Range Resources can ship purity NGL products direct to customers and realize an expected gross increase in incremental NGL pricing of $12 million-$15 million annually by eliminating all intermediate transportation charges before freight costs to the customers when the railroad loading facilities are completed, Pitzarella concludes.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.