Industry Financial Strategies

Workforce Dilemma Requires Action

By Mark Rubin

RICHARDSON, TX.–What happened to the big crew change?

For the past several years, one of the top priorities and challenges for the oil and gas industry has been trying to find the next generation of petroleum engineers and geoscientists. This has been the topic of many panels at conferences, articles in both trade and general business publications, and listed as a top concern of exploration, drilling and production industry executives.

With widespread projections of a talent shortage resulting from the graying of our profession, universities expanded their petroleum engineering programs and have been actively recruiting students to prepare for careers in the oil and gas industry. Competition to hire these new graduates heated, and they had their pick of multiple job offers with record starting salaries. The business press also helped in recruiting by publicizing that petroleum engineers were a hot commodity.

Fast forward to 2010. Petroleum engineering students expecting to graduate in May are worried about getting jobs in the industry that they have trained for.

No one counted on a global economic recession that has caused many experienced professionals to postpone their retirement, delaying the long-anticipated “brain drain.” With lower revenues, companies have reduced or put a hold on recruiting new graduates. We know that this industry has cycles, and that the need for petroleum engineers is going to rebound. But what happens to these 2010 graduates?

The Society of Petroleum Engineers is working with others in the industry to let companies know they have an unexpected opportunity to tap into the talent pipeline now, and recruit these talented new graduates.

Exploration and production companies of all sizes have a real opportunity to take steps in 2010 to address the shortage of engineering talent expected in the next decade, especially in the United States and Europe.

Key factors that are creating this opportunity include an increase in the number of graduates in petroleum engineering programs, which is creating the largest pool of young engineers seeking entry into the oil and gas industry in 20 years.

In addition, the global recession has caused experienced professionals to postpone retirement, offering a window of opportunity to transfer their knowledge to these new entrants. These students can contribute very quickly, and companies that act now can begin developing new entrants into autonomous professionals who have the complex decision-making ability required to exploit advanced technology.

Scaling back on new-graduate recruiting in 2010 could lead to a permanent loss of this talent as well as chill the interest of future engineering students in pursuing careers in the oil and gas industry.

Companies that can tap into this new talent pipeline will be better positioned to take advantage of the next economic growth period than their less forward-thinking competitors.

The Supply Picture

Over the past five years, petroleum engineering programs have been successful in increasing their numbers of graduates in response to widely discussed concerns about the aging of the oil and gas industry workforce, and the massive retirements of experienced professionals, who will need to be replaced in the next decade.

Although the so-called big crew change has a greater impact on personnel needs in the United States and Europe, companies in emerging oil and gas areas also have significant needs for engineering staff, further challenging the talent supply. The shortage of human assets has been listed among companies’ top priorities for several years.

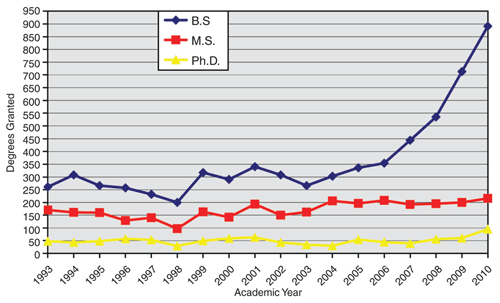

To meet the projected needs for petroleum engineers, universities around the world have increased enrollment in their petroleum engineering programs. For example, the number of bachelor degrees awarded by U.S. universities has nearly tripled in the past four years (Figure 1).

At a meeting sponsored by the Society of Petroleum Engineers with the heads and chairs of the petroleum engineering departments for universities in the United States, enrollment data were shared that indicate total enrollment has leveled, mainly because many of the universities are capping enrollment as a result of space restrictions and the number of teaching professors. As such, department heads expect the number of total graduates in 2011 and beyond to hover around 1,000-1,200 a year.

Although SPE does not have data aggregating the number of petroleum engineers graduating internationally, department heads at major universities around the world also report they have more students studying petroleum engineering.

Seizing Opportunity

The global economic recession has caused many experienced professionals to postpone retirement. This has enabled companies facing lower revenues to reduce or put a hold on recruiting new graduates.

As a result, the number of jobs being offered to graduates is being reduced just as the pool of resources has been enlarged. In 2009, more than 90 percent of petroleum engineering graduates from U.S. schools were offered jobs or went to graduate school. However, according to feedback from the college department heads, the approximately 50 oil and gas companies that recruited on campus in 2008-09 estimate they will hire only about 70 percent of available graduates this year, which will lead to about 300 graduates left without jobs.

Company reports and information from WorldWideWorker.com, which provides the job board for SPE student members, also confirm that global hiring plans are expected to be substantially lower in 2010.

The increase in the number of graduates at a time when companies are retaining more of their experienced staff represents an unexpected opportunity to immediately begin preparing for future workforce needs. Forward-thinking companies can seize the moment to recruit engineering graduates from the larger pool graduating this year, and to begin transferring knowledge from experienced workers who have postponed retirement. This will better position these companies to take advantage of the next economic growth period.

The average age of SPE members is now 46, which is a slight decrease as a result of a number of young members entering the industry. A gap in members aged 35-48 persists, reflecting the lack of hiring in the 1990s.

A 2008 human resources benchmark study prepared for SPE by Schlumberger Business Consulting shows that the fastest companies take six-seven years to develop new entrants into professionals who can work autonomously because of the complex decision-making and ability to exploit advanced technology that is needed by today’s professionals. The report concludes that human capital is the longest lead-time component of the exploration, drilling and production cycle.

The recession will end, and energy demand will rebound. The baby boomers in the industry will retire, and the forecast big crew change will occur. The lessons of the 1990s should not be forgotten. There is a significant downside to not taking advantage of this opportunity to recruit the expanded class of new graduates in 2010 and the next several years: the potential loss of these engineering graduates to other industries.

Graduate Job Board

SPE and WorldWideWorker have created a site with profiles and resumes of students who are preparing to graduate in 2010, as well as those who have graduated in the past two years. Hiring companies can see the profiles at no charge to identify potential new employees. This database of worldwide graduates is available at http://www.worldwideworker.com/graduate-jobs.

SPE also is working with other industry and professional societies, including the Independent Petroleum Association of America, to build awareness of the opportunity to hire new graduates.

Companies can gain access to well-trained, enthusiastic young people who have committed their careers to the oil and gas industry. Some companies are offering internships to these new graduates as an option as well.

Editor’s Note: Many of the industry technical societies as well as producer/operator associations maintain extensive personnel resource databases and on their Web sites. For additional information, visit the SPE, IPAA or the Society of Exploration Geophysicists.

MARK RUBIN was appointed executive director of the Society of Petroleum Engineers in August 2001. Prior to that, he served as upstream general manager for the American Petroleum Institute in Washington. Rubin joined API in 1988 and held a series of positions, working on federal regulatory and legislative matters as well as developing technical standards. Rubin held petroleum engineering positions for Unocal in Houston and East Texas from 1981 to 1987, and for Buttes Resources in Dallas in 1987-88. He is a member of the American Society of Association Executives and the Council of Engineering and Scientific Society Executives. He also has been a member of the National Petroleum Council, the Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission and the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers. Rubin earned a B.S. in petroleum engineering from Texas A&M University and an M.B.A. from Southern Methodist University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.