Digital Insights Boost Consistency Of Completion Operations

By Colter Cookson

Like drilling crews, completion teams are getting faster and smarter. By leveraging digital technologies to scrutinize every step of the process, from completion design to proppant delivery, pump maintenance and wireline procedures, they are slashing nonproductive time and putting more proppant down hole. Those optimization efforts will continue, but as the industry evolves, the mandate for completions is broadening.

“There has been a shift in what operators want from completion companies,” assesses Ben Dickinson, vice president of strategy and digital for NexTier Completion Solutions. “We still need to be efficient—which means minimizing nonproductive time—and emissions-conscious, which has made dual-fuel or electric fleets the equipment platforms of choice. But today, operators increasingly mention consistency, agility and collaboration.

“As an industry, we have figured out how to pump quickly and efficiently. Crews today are capable of 20 or more pump-hours per day and constantly break performance records,” he reflects.

Minute By Minute

“To help customers forecast costs and timelines reliably, we must be consistent enough to sustain that strong performance day after day across an entire job and then replicate it across multiple basins,” Dickinson observes. “At the same time, we are working with operators to ensure every minute of pumping contributes to recovering oil and gas from the ground.”

Data will help unlock reservoirs’ full potential, Dickinson says. “With the historic data now available, we can train machine learning models to predict how changes to completion designs will affect ultimate recovery,” he says. “As edge computing and cloud-based platforms improve, we will be able to apply those models in real time to generate recommendations and make adjustments from stage to stage.”

The models will need to be trained on the right data to deliver accurate recommendations for a given application, Dickinson mentions. Noting that the data will not work for training or analysis unless it is formatted and labeled in a uniform way, he says pressure pumpers are automating data collection to save time and minimize errors.

“We are past the point where a field engineer manually enters data into a spreadsheet or a platform at the end of stage, then sends it to customers so they can import it into their systems,” he says. “Today, we stream the data into a customer’s database in real time, with no human involvement.”

Automation is progressing beyond data collection. “We are seeing autonomous equipment that knows what to do and how to do it based on a set of parameters,” Dickinson reports. “Right now, that level of automation mostly applies to ancillary equipment, such as wellheads, wireline units and pressure testing equipment. For example, the valves on wellheads will open and close based on sensor data and digital handshakes.

“The piece that remains to be fully automated, but that several companies are working on, is running the frac equipment itself,” Dickinson relates. “Taking automation to this level will require a data standard for completion operations similar to the one for drilling. Without that base layer of shared understanding to build on, it will be hard for anyone to develop the necessary machine learning or control protocols to govern processes safely and efficiently.”

The completion industry is moving toward greater standardization, Dickinson assures. He says that is partly driven by operators’ growing desire for greater visibility into completion operations.

“In the past, an operator simply may have wanted to know how we can ensure we will be able to pump a certain number of hours a day across an entire program. Now we make that commitment, explain how we are going to achieve it, give data to support that forecast and highlight any potential risks that may disrupt the plan,” he describes. “Operators share more information with us as well. That way, we all can plan more effectively and take proactive steps to minimize risks, which leads to a lower cost per lateral foot completed.”

Remote Operations

A broad perspective can have a tremendous impact on completion operations, Dickinson says. As a case in point, he cites NexTier’s experience digitizing its wireline and pump down services so they can be supported remotely at its operations hub in Houston. “In the first three months after that change, we decreased wireline-related failures by 65%,” he reports. “It was an absolutely incredible response.”

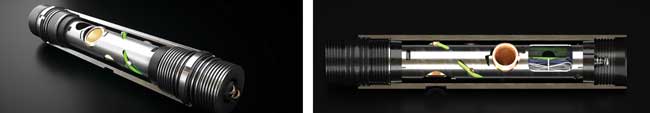

Electric hydraulic fracturing pumps such as this one are being deployed in spreads that primarily contain dual-fuel pumps. According to NexTier Completion Solutions, this hybrid approach makes it easier to optimize loads across pumps, which improves efficiency and performance.

That improvement came from a bird’s eye view. “For an individual wireline engineer who is only focused on one stage or one job, it’s impossible to see how every engineer who has touched that cable and every run into a well affects the cable’s overall life,” Dickinson says. “In contrast, our wireline engineers in the hub can look at the bigger picture of how all our trucks are operating, the tension profiles and speeds they are using, and what those mean for failure events. Changing procedures based on that analysis significantly reduces failures.”

As a next step, Dickinson says the wireline team plans to automate pump down processes. “The more consistently we deploy tools from stage to stage and day to day, the longer each cable is going to last and the easier it will be to predict issues before they cause nonproductive time,” he explains.

NexTier also is using data to refine preventative maintenance on its pump trucks, Dickinson mentions. “By pairing static data from maintenance records with live data from sensors on equipment, we are giving equipment technicians a second set of eyes to help them preserve equipment,” he says. “Over the past six years, our system has evolved to use complex, multivariable alarms that compare live data with historical variances to forecast potential failures. This helps our teams do the right maintenance to keep jobs running smoothly.”

The effort has paid off, Dickinson assures. “We have been able to increase engine life by 115%, transmission life 65% and power end life by almost 120%,” he details. “That is a huge increase in mean time between failures, and it’s also translated into a lower total cost of ownership for equipment.”

The remote operations hub also houses operations engineers. “This lets us maximize the potential of our degreed professionals,” Dickinson says. “In the past, they would spend an entire shift in a frac van in the middle of West Texas, the Bakken or Appalachia to oversee a single job. By working with customers to develop data acquisition systems and automating routine tasks at every step, from design to execution and billing, we have empowered each engineer to handle four or five jobs simultaneously. We still have engineers in the field to support crew, but their focus is on ensuring strong service. Traditional field engineering now takes place in Houston at scale.”

According to Dickinson, going remote has improved the quality of a key deliverable. “Once all the proppant is on site, the equipment is set up, and the job is pumping, the end product that operators want from a completions company is data,” Dickinson clarifies. “That data needs to be as accurate as possible and integrate into customers’ databases.”

Not all of NexTier’s customers want data the same way, so it needs to be customized for each operator, Dickinson relates. “Working at the hub has helped concentrate engineers’ attention on enhancing data deliverables at a fast pace,” he comments. “Instead of being isolated in a van that may be in an area without cell service, the engineers are in a place where they can collaborate across basins, crews and shifts. In the past, changing how we gave data to a customer could take hours, days or even weeks. Today, we can implement a change across the United States in about 10 minutes.”

While it’s unlikely diesel fleets will phase out entirely, Dickinson says natural gas-fueled fleets have recently taken over the majority of activity share. “Because natural-gas-fueled fleets provide both lower fueling costs and lower emissions, we have seen a steady transition to dual-fuel fleets and electric fleets powered by natural gas generators,” he reports.

“Operators who question how far they want to go into the e-fleet realm are experimenting with hybrid fleets that have one or two electric pumps supplemented by dual-fuel units,” he continues. “This gives operators a chance to get comfortable with the equipment. At the same time, our crews can put more of the horsepower requirements on the electric pumps, which helps level loads across the rest of the fleet for optimal efficiency.”

Perforating

Like most aspects of completions, perforating is becoming more nuanced, observes Ryan McNeely, senior business development manager at GEODynamics. “Ten years ago, it was common for operators to say, ‘just give me a perforation and I’ll frac it,’” he recalls. “Especially in the past two or three years, they pay more attention to perforating designs and want to have technical, high-level conversations about how we can help them place proppant more effectively.”

One way to increase efficiency is to use fully integrated perforating guns, says Zach Wade, the company’s senior operations manager. “The turnkey guns arrive fully loaded, enabling wireline crews to get in and out of the hole as fast as possible,” Wade describes. “All they need to do is screw the guns together and the guns are ready to go down hole.”

The turnkey approach liberates the wireline company from several hassles, Wade says. “There is a lot of paperwork associated with shipping hazardous materials, including documentation for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms that comes with some long-term complexity,” he illustrates. “With the integrated system, companies only need to make a call for the guns to show up on site ready to go. There is no need to combine a charge from one company, hardware from another and telemetry from a third.”

That simplicity means an on-site crew of three-five people can handle jobs that traditionally require a loading shop, a driver and a truck, Wade comments. He says the smaller workload is particularly beneficial when considering overhead costs, operating efficiency and the industry’s workforce challenges.

To save time, many wireline crews prefer integrated perforating guns that are loaded at the factory (left). Such guns have established a track record of reliability and risk reduction, GEODynamics reports. However, the company says more traditional guns that are loaded at a wireline provider’s gun shop (right) will continue to see use in many applications. Their flexibility enables changes to perforation designs from stage to stage that can improve the well’s performance.

The guns can be shipped as 1.4D or 1.1D explosives. The latter costs more, but because it allows more guns to be included in each truck, Wade says it sometimes reduces overall costs.

“With a 1.1D shipment, we install the intrinsically safe switch/detonator module in the factory, which ensures safe transport and eliminates the need for crews to do this on site. That is a huge advantage for companies,” he adds. “Wiring a detonator is a delicate process. It predominantly involves cutting, scotch locking, and inserting the detonator into a detonator block on the cord. Each step must be completed precisely and safely to help prevent failures down hole.”

Quality Control

When integrated guns first entered the market, they faced skepticism from field crews that were comfortable with loading and troubleshooting traditional guns, McNeely recalls. He says that wariness has faded as experience has shown that integrated systems work reliably and reduce failure risk. “In fact, feedback on the integrated system has only been positive,” he says. “Crews love the simplicity of making guns up. They can test the gun string to verify everything is working correctly, then devote their time and attention to other tasks.”

Getting to that simplified operation requires strong quality control, Wade says. “At every step of the way, from manufacturing the hardware and explosives through assembly and loading, we go through a thorough quality control process,” he assures. “We mark the components so we can verify that previous checks have been performed. In shipping, we do one last check to address any potential issues before the gun arrives at its destination.”

Thorough quality control means the guns work as expected, Wade and McNeely report. “We have experienced personnel we can dispatch to a site quickly, if needed,” McNeely adds. “Phone support is valuable, but wireline crews appreciate that we can send someone to their location to offer hands-on support.”

Although the integrated guns generally save time and money, McNeely says job requirements and service company needs ultimately determine which gun system is selected. For example, wireline crews sometimes choose charges, detonators or switches from other companies to meet operator specifications, work through existing inventories or stick with familiar processes. To meet these crews’ needs, GEODynamics has introduced a variant of its new gun system that has an open architecture.

Wade points out that loading charges into an open architecture gun at the wireline provider’s gun shop enables on-the-fly adjustments during a job and helps eliminate excess charge inventory. “If any changes are made to the perforating design during a job, a wireline operator can easily adjust their telemetry or charge configuration before the next stage to enhance performance,” he says.

“We are seeing a heavier focus on oriented perforating because the right orientation pattern can improve proppant placement,” McNeely adds. “The next big advances in perforating guns will likely involve improvements to the orientation process.”

With that in mind, Wade says GEODynamics is testing self-orienting guns. “Today, we orient guns with lock ring subs, which work well but require manual processes,” he says. “Self-orienting systems will let wireline crews achieve the desired orientation with less hardware and manual labor.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.