Creative Approaches Help Simplify Permitting For Much-Needed Pipelines

By Gary Kruse

As the Mountain Valley Pipeline struggles to reach completion and New York continues to block all paths north, many are saying that if MVP ever is completed, it may be the last pipe out of the Marcellus/Utica. If that were to happen, current egress capacity for the region would become a permanent limit on annual production from the largest natural gas basin in the country. And only 600 miles away, its neighbors in New England would continue to rely heavily on liquefied natural gas imports to heat homes.

Transcontinental Pipeline’s Regional Energy Access (REA) project may offer a path for other pipeline developers to follow. By limiting new construction to welcoming states and otherwise using compression, it may have found a way out of the region–with one caveat.

New England’s Need

Expanding pipeline capacity to New England is critical. In September, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission hosted a forum to discuss the state of New England’s gas and electric energy grid. In anticipation, ISO New England and the region’s gas and electric distribution companies issued a joint “problem statement and call to action” to “help inform the discussions” at that forum. This statement notes the transition to a cleaner energy future requires the region to reduce its reliance on imported LNG.

The statement also observes that until New England develops renewable sources of generation and the related long-duration resources needed to balance variable production, it will remain dependent on natural gas and imported LNG to reliably provide heat and electricity. “Without adequate gas, the region may not be able to meet the demand for home heating and electricity–and, when reliability suffers, the clean energy transition suffers.”

That news should not shock anyone, although it seemed to surprise one FERC commissioner. After the forum, Commissioner Allison Clements tweeted she was “struck by how long this conversation has been going on,” and said FERC should chart a course toward “actionable solutions.”

New England’s lack of gas supply may be most directly linked to one day in June 2013 when Constitution Pipeline filed its application to build a 650,000 dekatherm/day project from the Marcellus Shale to New England. That project–which was never built–was the first of many FERC-approved pipelines that ultimately would be blocked by opposition groups intent on “keeping gas in the ground” by preventing it from reaching demand centers.

In a curiously similar sentiment, FERC–particularly Commissioner Clements and Chairman Richard Glick–has sought to become an environmental regulator, intent on rejecting any pipeline expansion solely because the transported gas’ end-use will emit greenhouse gases. This position was most forcefully asserted in two policies FERC issued in February and quickly withdrew in March following substantial blowback from Congress.

For now, there appears to be a working majority, including the two Republicans and other Democrat, Commissioner Willie L. Phillips. These three commissioners’ records show they will continue to approve projects based on the policy in place before February 2022. But even under that policy, first adopted in 1999, pipeline developers may need to get creative to maximize their projects’ chances of completion.

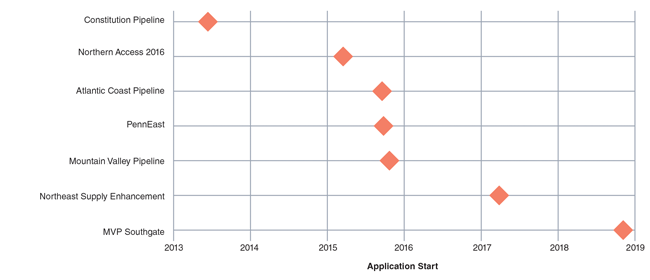

While the Constitution project is a poster child for FERC-approved pipelines that have been canceled in response to opposition, it is not alone. Since its application was filed in 2013, the other projects shown in Figure 1 met a similar fate.

The Clean Water Act

The tactics used to stop the unsuccessful pipeline projects varied. A common one relates to the Clean Water Act, which gives each state the right to review any project crossing its wetlands and waterbodies to determine whether the proposed activity will violate its established water quality standards. New York and New Jersey have used these reviews as both a delaying tactic–by extending the review period beyond the one-year limit imposed in the statute–and as grounds to deny an approved project by finding it will be in violation.

Opposition groups similarly have challenged states’ decisions to approve projects by claiming the approval process fails to comply with the state’s procedures or improperly deems the project compliant.

Senator Joe Manchin, D-W.V., included language to correct some of these issues in a permitting reform bill he proposed, titled the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2022. However, that provision was struck from a version proposed as a rider to a must-pass bill for funding the government that passed in September. Purportedly, negotiations continue to include some version of the bill as a rider to the defense appropriations bill, which needs to be approved in December. But as of late October, it remains unclear whether any changes to the CWA can receive enough support to be included.

As is, the CWA gives states a tool for blocking projects they deem unnecessary. States are not supposed to reassess a FERC determination that a project is in the “public convenience and necessity,” but several have used their authority under the CWA to reject projects for which they openly question the need.

Other Obstacles

Almost every state owns many acres of land outright, and some states have taken conservation easements over land they do not own. States have used landowner status to block or delay the routing of a project–both by denying access to the land needed by the project to conduct environmental studies and by prohibiting use of the land for facilities FERC has approved. In a case involving the PennEast pipeline (one of the canceled projects in Figure 1), the U.S. Supreme Court held pipelines can condemn state-owned land, but as landowners, states still can substantially delay projects.

The federal government also owns large areas of land and can designate areas as national parks and national forests. While national parks essentially are off-limits to pipelines, this is not the case for national forests. However, crossing them has recently and repeatedly become an obstacle for project developers because opposition groups can challenge the federal government’s decisions to approve pipeline-related land use. Federal ownership may become an even bigger obstacle if the federal government becomes more hostile to pipeline development.

Even on privately owned land, activities must comply with the Endangered Species Act. Sometimes opposition groups have challenged federal approvals as insufficiently protective. These challenges, like those to grants over federal lands, have slowed reviews and led to approvals being reversed and the review process starting over.

As part of their permit applications, developers must demonstrate a project causes no harm to any land or historical locations in which a recognized Native American tribe has an interest, even if the project’s route does not cross that land. Similarly, nontribal land or objects of historical importance may not be adversely affected by a project. Both these stipulations have delayed projects, although not as significantly as the previously discussed issues.

Environmental justice always has been a concern during FERC project reviews. This consideration has become more prominent as several federal agencies have begun to recognize that historical development had a larger impact on low-income and minority populations. Planned projects traversing the same areas may perpetuate the disparate impact on those communities; this concern already has led to project delays and its attention in the review process is expected to increase.

Possible Paths Forward

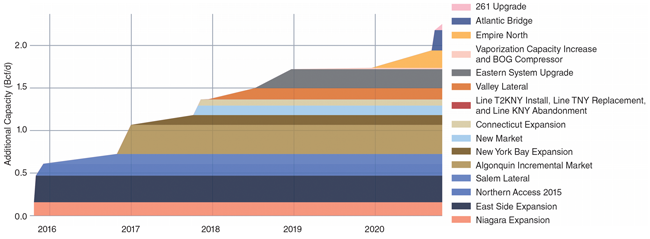

As shown in Figure 2, several projects managed to be permitted and built during and after the Constitution Pipeline saga. More than 2 billion cubic feet a day in capacity was added to various areas from New York through New England. But even for successful projects, the path is not short. For the projects in Figure 2, the time from when they first approached FERC to when they were placed into service ranged from 20 to 67 months, with the median right at three years.

It has been difficult to build new projects in the region, but not impossible.

To maximize their chances of success, pipeline developers may try to limit work in hostile states. This is the approach Williams’ Transcontinental Pipeline is using for Regional Energy Access, a project pending before FERC to provide an additional 820,000 dekatherms a day of capacity from the Marcellus/Utica region with deliveries along the East Coast. Most of the anchor shippers are local distribution companies.

That additional capacity is created through a combination of new pipeline (about 36 miles), installation of one new electric-driven compressor, and increasing horsepower at five existing compressor stations. Critically, the pipeline additions are limited to Pennsylvania, a state that has not yet joined its neighbors in using the water quality certificate process to block projects. For REA, Pennsylvania took the full year available under the CWA to make its decision, but ultimately approved the project–even before a FERC ruling.

Although REA has not yet received FERC approval, its strategy may be replicable for projects into the New England region. One concern, though, is a major change to FERC’s Certificate Policy Statement that the commission introduced in February but then quickly withdrew in response to Congressional scrutiny.

While Chairman Glick regularly describes the revised policy statement as a refinement of the 1999 policy, it rejected wholesale a key component of that policy. Specifically, in the 1999 policy, FERC generally removed itself from the role of determining project need. The old policy statement did not forbid FERC from weighing other evidence, but made it clear that the agency considered binding precedent agreements–particularly with unaffiliated shippers–as conclusive evidence a project was needed.

The revised policy adopted by FERC in February completely abandoned this concept and restored FERC to the role of omniscient predictor of the future, by installing it as the ultimate judge of need. Instead of treating contracts as a clear indicator of demand, the policy held that FERC should make decisions based on its own views of reports by “experts’’ about future gas demand in a region.

The risk of this drastic change already is playing out with respect to REA. To stop the project, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU) and the New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel have argued that there is no need for the additional capacity REA would create.

SJI Utilities, the company that owns two of New Jersey’s gas utilities, filed a response for its subsidiaries, Elizabethtown Gas and South Jersey Gas. That filing noted a key fact: it is the utilities themselves under New Jersey law–not the BPU–that are charged with being the “providers of last resort” and ensuring “the adequacy of gas supply and associated pipeline capacity to serve the full needs of their customers.” As stated in the filing, the two subsidiaries have “entered into a binding precedent agreement with Transco to meet approximately 25% and 34%, respectively, of their projected increases in demand over the next 10 years.”

Although the letter does not go so far as to say that should end the discussion on need, it does note the utilities’ assessments are “not based on speculation–they are based on a market-driven need.”

A Second Strategy

Another strategy that can be deployed to expand New England’s pipeline capacity is to replace older pipelines in the region with newer, larger-diameter pipelines and combine that with retiring older gas-driven compressors in favor of electric-driven compressors.

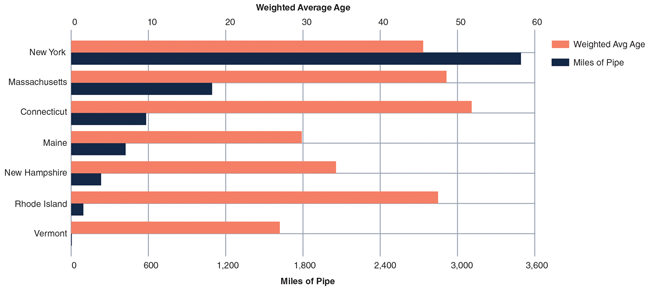

As shown in Figure 3, states with the most pipe in the region–New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts–also have some of the oldest pipelines. This creates an opportunity for growth projects that will replace the aging pipelines, through a lift and lay process with larger-diameter pipelines. Such upgrades will improve the safety and reliability of existing infrastructure, which may be more acceptable than greenfield pipelines such as Constitution.

It helps that existing compressor stations are likely to be gas-fired. Replacing them with electric-driven compressors reduces pollution and noise. For stations located in low-income or minority communities, going electric also promotes environmental justice.

Whether limiting pipeline construction to friendlier states and upgrading existing pipelines will be enough for projects to overcome regulatory roadblocks remains to be seen. But these methods have the best chance for success in a difficult area of the country that is in desperate need of increased gas supplies.

Permitting Reform

Senator Manchin’s permitting reform bill, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2022, addresses several issues facing energy infrastructure projects, including natural gas pipelines. While some of its provisions may be helpful, none of them are silver bullets, so project developers still need to be creative.

Aside from the revisions to the CWA mentioned previously, the bill seeks several changes that can support natural gas pipeline development. First, it establishes timelines for FERC to prepare environmental assessments and environmental impact statements. These are timelines FERC generally has met before the current commission, so this provision’s impact may be limited.

Second, the bill requires the president to:

- Establish a list of projects of strategic national importance, of which “five shall be projects to produce, process, transport or store fossil fuel products, or biofuels, including projects to export or import those products;” and

- Direct federal agencies to prioritize completing environmental reviews and authorizations for such projects, including those remanded or vacated by courts.

Manchin’s proposal also directs federal agencies to issue biological opinions, incidental take statements, rights-of-way, amendments, permits, leases, verifications and other authorizations to enable completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline; declares these actions exempt from judicial review; and gives the D.C. Circuit jurisdiction over any challenges to the statute.

Democratic leaders ultimately stripped permitting reform from the continuing resolution approved in September after it became clear the measure lacked the needed votes. However, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., reportedly has agreed to attach it to the defense appropriations bill expected to be approved in December. Encouraging signs suggest that some Republicans may be willing to vote for a modified, “bipartisan” version of the bill in December, support that likely will be necessary to overcome progressive Democrats’ opposition. These machinations mean the renewable industry, the fossil fuel industry and especially Mountain Valley Pipeline likely will remain on pins and needles for another couple of months.

GARY KRUSE is managing director of research for Arbo, which provides energy regulatory intelligence data, software and services to pipelines, producers, policymakers and trading houses. Kruse has decades of experience assessing how regulatory, litigation and market dynamics impact energy infrastructure’s development and operation. By combining data and quantitative analysis with context from economic, political and market trends, he has helped executives, policymakers, and commodity traders decide how to deploy capital, minimize risk and maximize returns. Kruse graduated from the University of Virginia School of Law and holds a B.A. in mathematics from the University of Dayton.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.