Spectacular Mega Deals Create Optimism, Suggest 2024 M&A Will Rise

By Brad Nelson and Charles Meyer

The mega deals of 2023 are only one of many factors that create room for optimism about a brighter mergers and acquisitions market in 2024. Recent economic indicators suggest that inflation is slowing, which can lead to lower interest rates. Oil prices continue to fluctuate, but not wildly so, and they remain well above $60.

Capital also may be more accessible this year. As environment, social and governance concerns have tapered to some extent, large investors may rejoin the market. Regardless, alternative funding sources, including family offices, are providing needed liquidity and reaping attractive profits.

To understand what 2024 and beyond may look like, it is helpful to look back at how the oil and gas M&A market reached this point.

Last year illustrated how difficult it can be to forecast merger and acquisition activity in the oil and gas market. Conventional wisdom holds that an oil price above $60 a barrel is an ample price to make M&A active. Although the spot price for WTI hovered in the low $70s and mid-$80s throughout 2023, deal flow was relatively low.

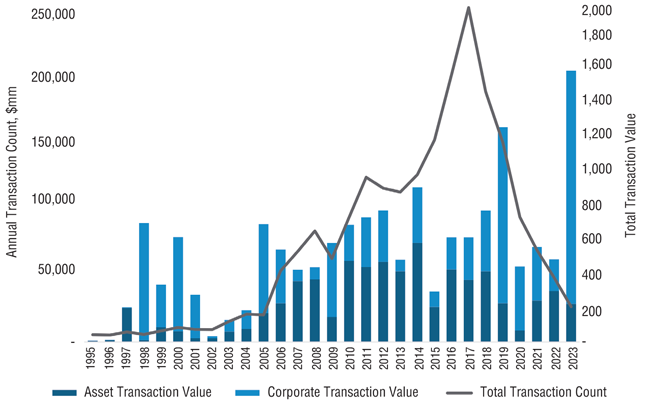

While the year did see several high-profile deals, such as ExxonMobil’s acquisition of Pioneer, overall deal volume fell to levels unseen since the early 2000s (Figure 1).

Among others, the primary issue is economic uncertainty. As always, would-be buyers need to make assumptions about commodity prices, which currently face downward pressure from economic forecasts that focus on inflation and see the potential for a recession. Global instability from multiple wars and tensions with China/Russia make the proverbial crystal ball even cloudier than normal.

Looking Back

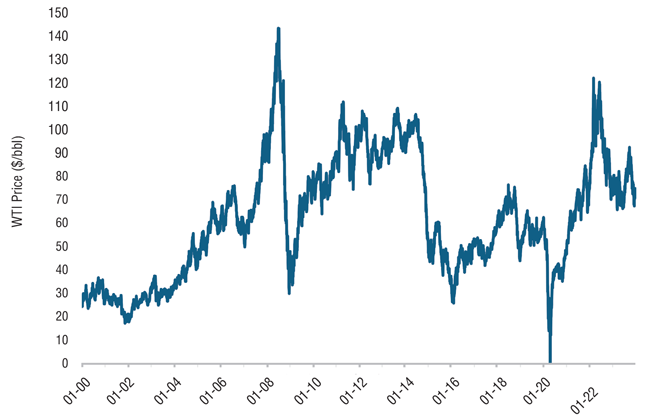

From the mid-1980s until the early 2000s, the price of crude oil remained steady at approximately $25 a barrel adjusted for inflation. That price did not result in significant profits, but it helped maintain stability in the global economy.

In 2003, oil prices climbed to $30, then $60 in 2005 and $147 in 2008. Several factors contributed to higher prices, including Middle East tensions, soaring demand from China, the falling value of the U.S. dollar, declining petroleum reserves, worries over peak oil and financial speculation. To take advantage of rising prices, oil and gas firms focused on growth and devoted significant capital to acquiring assets.

From 2000 to 2008, transaction volume grew significantly. During that period, data from Enverus indicates the upstream industry announced transactions totaling $400 billion across more than 2,000 deals. This era also saw the beginnings of the shale revolution. In 2001, Devon acquired Mitchell Energy, one of the earliest shale deals.

By 2010, more than half the wells drilled in the United States were horizontal. In the preceding decade, Barnett production alone grew thirtyfold.

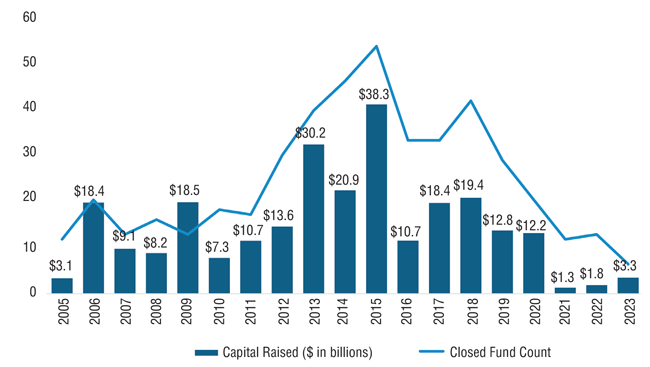

Prices held steady from 2011 to the fourth quarter of 2014 (Figure 2). This “golden era”—with steady prices and vast new resources being tapped—saw ExxonMobil claim the title of world’s most valuable public company by market cap. On the private side, new money rushed into the industry. More than $30 billion was raised for the oil and gas industry in 2013, triple the average from 2005 to 2010, according to PitchBook.

Private equity helped fuel M&A activity. From 2009 to the end of 2014, more than $500 billion in upstream deals were announced across almost 5,000 transactions.

As shale enabled the United States to increase production, the global oil and gas market took notice. Near the end of 2014, Saudi Arabia initiated a price war that caused prices to fall from nearly $100 late that year to a low around $25 in early 2016. The primary goal was to crash oil prices so shale production would become unprofitable.

This crash was one of the quickest and deepest in oil history. Hundreds of billions of dollars of public and private capital were erased from conventional energy companies. According to Haynes and Boone, more than 100 oil and gas companies filed for bankruptcy in 2016.

Still, the American shale industry proved resilient. As advances in drilling and completion techniques led to more productive wells, companies experimented with tighter spacing, notably in the Permian.

Because the Permian’s many viable zones appeared to offer almost limitless resources, it became a magnet for capital. Abundant capital supported a dealmaking frenzy called “Permania.” From 2015 to the end of 2019, $400 billion in upstream deals were announced across more than 7,000 transactions.

But after years of tremendous production growth, U.S. investors saw little free cash flow and cooled on further investments. At the same time, ESG concerns began to intensify. Transaction volume peaked in 2017 and soon began a precipitous fall. By 2019, Enverus data indicates that deal volume had dropped 40% from the 2017 peak.

The COVID Chill and Recovery

As COVID-19 swept the world and crude prices plummeted, ESG pressure reached its zenith, with numerous institutions pulling fossil fuel related investments. Private equity fundraising fell approximately 90% from amounts raised only a few years earlier (Figure 3).

2020 still saw more than $50 billion in deals. However, the deal count plunged, and most of the announced value was in corporate consolidation. For a while, asset markets appeared frozen thanks to a bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers that was wider than any in recent memory.

But a recovery soon began. By late 2020, oil prices rebounded. By mid-2022, the war in Ukraine briefly pushed oil prices beyond $100 a barrel, though they tempered later that year to $70 on recession fears.

Traditional energy representation in the overall S&P 500 rose from a low of 2% at the end of 2020 to 5% in 2022. Value beat growth and capital discipline became the primary focus for operators.

The 2023 Puzzle

In 2023, deal counts fell below historical trends despite a reasonably healthy price environment.

Inflation is one of the main reasons for the low deal volume. Economic conditions stemming from the pandemic caused the global inflation rate to rise from 3.25% in 2020 to 4.7% in 2021, then 8.7% in 2022. During the 2022-2023 inflation spike, oil and gas capital costs experienced particularly acute inflation because of higher steel prices, labor shortages and fuel costs, all of which stemmed from the post-COVID economic rebound.

To combat accelerating inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates. In March 2022, the federal funds rate was zero. Since then, the rate has increased 11 times—most recently in July 2023—to a target range of 5.25%-5.50%.

These efforts may be paying off. From January 2023 to November of that year, U.S. monthly inflation fell from 6.4% to 3.1%. However, the cost of borrowing has increased nearly twofold in two years. Higher rates are especially challenging for smaller producers.

With the Fed hitting the brakes on the U.S. economy, along with war in Europe and warning signs in China, investors are hyper-focused on signs of slowing demand in these three key regions of consumption. This demand uncertainty complicates dealmaking by increasing bid-ask spreads.

While the ESG wave limited the oil and gas industry’s access to capital, its influence is receding. Consider the wave’s effect on stock prices for majors in Europe and the United States. European companies have struggled to realize sufficient returns from substantial green energy investments, and their stock prices have lagged those of their U.S. peers, who invested through the trough in conventional energy prices.

ESG concerns continue to be felt in the private equity world. Private equity’s primary investor base is institutional, notably endowments and pension funds. Anti-fossil-fuel mandates and other ESG ramifications have reduced private equity’s ability to raise capital for oil and gas activity dramatically, which has materially impacted the industry.

Regulated banks also have backed away from financing oil and gas. Traditional debt is harder to raise than it was only a few years ago, and several lending banks have pulled out of the industry entirely. Those that remain generally offer less capital and less favorable terms.

Looking Forward

Despite these headwinds, there are at least two signs that oil and gas transactions may rebound.

The first is the increase in consolidation currently taking place. Last year continued the trend of splashy corporate deals that became front and center beginning in 2020. ExxonMobil’s $59.5 billion purchase of Pioneer epitomizes this trend.

In years past, consolidation was followed by an increase in asset sales as consolidators streamlined their upsized portfolios to focus on the most attractive opportunities. There is ample evidence to think the post-deal divesture trend will repeat. After closing on its $53 billion acquisition of Hess, Chevron plans to increase its divestiture program to generate $10 billion-$15 billion in pre-tax proceeds through 2028.

Other large players likely will follow suit. When Occidental announced its agreement to acquire CrownRock for $12 billion in cash and stock, it launched a $4.5 billion-$6.0 divestiture program. Coupled with increased cash flow, the company hopes proceeds from the program will enable it to reduce debt and retain its investment-grade credit ratings.

With inventory quality and depth front-of-mind for investors, sellers should find a robust buyer pool. While larger public companies have made headlines with their considerable consolidation spend, small to mid-cap public companies have outpaced their bigger brethren in deal count for the past two years. These smaller firms see transactions as an excellent way to shore up inventory.

Drawing New Investors

Private equity’s drawdown has created an opportunity for other sources of funding to take its place. These include family offices, which have quietly supported oil and gas activity at a smaller scale. Today, investing in traditional energy is seen as a contrarian value position, an investment theme that many family offices favor. These investors frequently offer the benefits of long holding periods and flexible deal structures.

Family offices often prioritize cultural fit and have more reasonable value expectations. In many ways, they are ideal investors for an industry that others shun, although their highly relationship-oriented investing style may differ materially from other capital sources.

Connecting with family offices sometimes can be a matter of networking and proper introductions. That networking should include reaching out to advisers who work with family offices frequently enough to know which ones are seeking new investments.

All that said, private equity remains somewhat active. Although fundraising is more difficult now than it once was, industry stalwarts such as EnCap, NGP Energy Capital, Quantum and Kimmeridge are successfully raising funds.

As the oil and gas sector’s strong profitability draws in new investors and renews interest from previous investors, funding transactions and other activities should become less challenging. This may enable more companies to pursue the assets that enter the market as consolidators rationalize their portfolios.

Editor’s Note: This material has been prepared solely for informative purposes as of its date of preparation. It is not a solicitation, recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security and does not provide information on which an investment decision to purchase or sell any securities could be based.

Stephens or its employees or affiliates at any time may hold long or short position in any of the securities mentioned and may sell or buy such securities. The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Stephens or any other person or entity.

Data referenced in this material is the intellectual property of those referenced and is protected under copyright law.

BRAD NELSON is a managing director for the energy and clean energy transition investment banking group at Stephens. Nelson joined Stephens in May 2009 as a managing director. Earlier in his career, Nelson served as a managing director at Energy Capital Solutions, where he was a founder. Before joining ECS in 2001, Nelson was an associate in Bear Stearns’ energy group, focusing primarily on transactions related to exploration, drilling and production and oil field services. Prior to joining Bear Stearns, Nelson was an associate with Koch Ventures, the private equity arm of Koch Industries. At Koch, he focused on providing private capital to energy and technology-related companies. “Stephens” (the company brand name) is a family-owned investment firm that includes Stephens Inc. (member NYSE/SIPC), Stephens Investment Management Group LLC, Stephens Insurance LLC, Stephens Capital Partners LLC and Stephens Europe Limited.

CHARLES MEYER is senior technical head for the energy and clean energy transition investment banking group at Stephens. Meyer joined Stephens in February 2020 as senior technical head in the energy group and currently leads Stephens’ upstream technical team. Meyer started his career as a reservoir engineer for ExxonMobil in 2009, where he supported numerous assets in progressively more senior roles. In 2014, he joined BNP Paribas’ oil and gas advisory team, and subsequently moved to UBS’ team in 2017. Meyer has advised on numerous transactions across the upstream space and has expertise in decline curve analysis, rate and pressure transient analysis and field development planning.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.