Data Reveals Ways To Address Emissions While Achieving Other Goals

By Colter Cookson

While the U.S. may be tempering its greenhouse gas-focused regulations, market forces will likely keep emissions top of mind for many companies. Strong environmental performance can help companies attract investors and employees. It is also required to sell liquefied natural gas to some international markets, including the gas-hungry European Union.

Over time, investors, regulators and other stakeholders have become stricter about emissions data, observes Chelsea Goral, strategic advisory lead for Highwood Emissions Management. “In the past, companies would estimate their emissions by counting the equipment they had, then multiplying those counts by emission factors based on studies of how that equipment type performs,” she recalls. “Measurements of actual emissions show these factors often overestimate or underestimate emissions.”

In some cases, the actual emissions can be ten times higher than expected, Goral warns. In others, they are significantly lower. As examples, she says the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s emission factors for pneumatic valves overestimate emissions because they assume the valves operate more frequently than they do. However, flares emit more than the industry once thought because of issues with flames going out or improper configuration.

As the industry has realized how troublesome flares can be, companies have begun replacing burner tips, installing flame monitors and paying more attention to how much air or gas assisted flares receive, Goral mentions.

“Discrepancies between predicted and actual emissions create some compliance and reputational risks. We are seeing some distrust among stakeholders of the emissions reductions companies report, which is driving a push toward estimates that are based on measurements at a company’s sites,” Goral relates.

She says robust measurement has many benefits. “Using realistic data and measurements to drive decisions helps save money and time by allowing companies to prioritize their mitigation efforts,” she illustrates. “At the same time, it demonstrates credibility and builds trust with the investors and the public.”

Collecting Data

In most cases, the first step to developing an effective emissions management strategy involves inventorying equipment, Goral advises. While emissions factors are far from perfect, they remain a valuable starting point for identifying the most material emissions sources, she explains.

“Next, we make a plan to measure the actual emissions,” Goral continues. “To minimize costs, we will group equipment that should behave similarly, then measure a representative sample. For example, we know that heavy oil assets will behave differently than pure gas plays, or that older pipelines made from less robust materials will likely emit more than newer ones.”

The groupings can be extremely detailed and technical, but Goral says most companies try to find a balance between thoroughness and efficiency. Data can be invaluable for prioritizing mitigation efforts, but there is a point of diminishing returns beyond which it’s better to focus on addressing known issues.

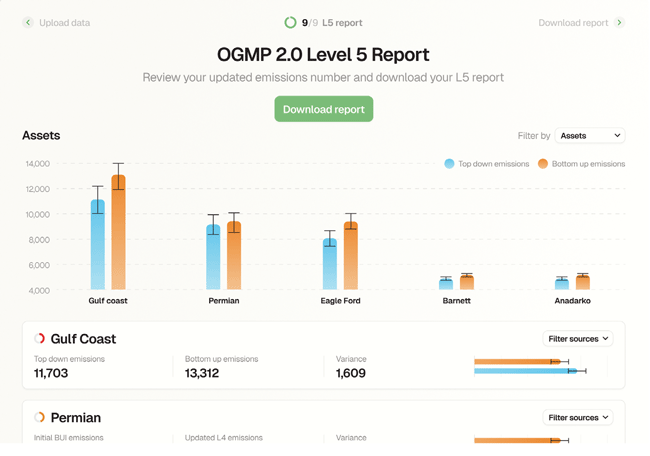

To demonstrate their emissions reduction prowess to investors and other stakeholders, many companies are embracing voluntary initiatives, such as the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership, that require measurement-informed estimates and careful bookkeeping, Highwood Emissions Management relates. The company says this trend has resulted in a need for software that streamlines reporting workflows and promotes consistency across companies.

To help companies optimize emissions detection, Goral says Highwood has developed a simulator that considers the strengths and weaknesses of various measurement technologies. “We can load historical emissions data for the types of equipment an operator has so the simulator can model the likelihood a leak will occur at each site and how severe that leak will be,” Goral describes. “Then we layer in various detection technologies and cost assumptions. Finally, we compare the results to see which technology combinations will give better emissions coverage.

“Emissions detection is not a problem with a silver bullet solution,” she stresses. “In the Permian Basin, where assets can be spread out, it may make the most sense to use a plane-based sensor that only picks up larger leaks but can cover a lot of ground. In Colorado, where emissions tend to be lower, a company might still fly a plane, but will usually do so at a lower altitude or use a more sensitive detector to pick up the emissions of interest.”

Software’s Role

As companies evaluate and address emissions sources, they will often end up with an ocean of data. “Processing and conditioning that data can be a big challenge,” Goral says. “For example, if a plane detects a methane plume, the company will have to evaluate whether it is a one-time event or a continuous problem, which can involve some investigative work.”

Fortunately, emissions management software can make such determinations much easier. Goral says it can also highlight discrepancies between expected emissions and actual emissions, allowing companies to investigate why they are occurring.

“We have built our emissions accounting platform to comply with voluntary initiatives, such as the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership,” she says. “Many of these initiatives require companies to compare emissions factors with actual emissions and to assign confidence levels to those measurements. In other words, how certain are they, and how big are the error bars?”

Creating uncertainty estimates can be complex and time-consuming, Goral remarks. “Measurement uncertainty can come from several sources,” she explains. “How likely is the technology itself to detect a leak? How often were measurements taken? If the measurement is a one-time snapshot, what assumptions need to be made to extrapolate that out and estimate annual emissions for comparison?”

Given the number of judgement calls involved, it can be easy for uncertainty assessments for otherwise similar situations to vary from company to company, Goral cautions. The voluntary initiatives offer guidelines for evaluating uncertainty and performing other tasks, but they generally focus on principles rather than defining workflows. She says the resulting inconsistency can make emissions reports less valuable for cross-company comparisons and less trustworthy to investors.

To address this situation, Goral says Highwood partnered with four energy companies that have assets across the world to develop sequential workflows for implementing the standards that are clearly defined and relatively easy to follow. “We have worked to apply methodologies and assumptions in a consistent way so that companies can provide stakeholders with measurement estimates that are transparent and credible,” she assures.

Extraterrestrial Insights

By using artificial intelligence to analyze satellite data, Satelytics helps operators detect emissions, pipeline leaks, erosion and other concerns, says Sean Donegan, the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“The scale satellites can cover in terms of infrastructure around the world is extraordinary,” he enthuses. “Today, the commercial satellite network is large enough that we can look anywhere in the world at least once a day. One of our most visionary customers, Hess, is checking its Bakken assets four times a week.”

By using machine learning algorithms to interpret satellite data, Satelytics says it can help companies detect a variety of issues, including methane and carbon dioxide emissions, erosion, shifts in water quality, surface disturbances and pipeline leaks.

Hess’ satellite program initially focused on quickly identifying leaks in produced water, oil or natural gas pipelines. Donegan says the company now leverages the data for numerous other purposes, including monitoring erosion along Lake Sakakawea and checking roads and pads for changes or damage.

“We have done a lot of methane detection for BP on both onshore and offshore assets,” Donegan adds. “In the midstream space, our clients include Enterprise Products Partners and Harvest Midstream.”

To monitor client infrastructure, Satelytics rents satellites or purchases data from companies such as Airbus, Maxar Intelligence, Planet Labs and TripleSat. Thanks to AI and the cloud’s near-infinite processing power, Donegan says the company can detect and alert operators about potential concerns within three or four hours of the satellite inspection.

Each alert includes information on the event type, location and severity. Clients can receive alerts by text or email, view a map or list of alerts in Satelytics’ Web-based platform, or integrate the alerts with work management tools such as Maximo, SAP or Dynamics 365, Donegan describes.

There is little risk of false alarms because all the company’s algorithms have an accuracy beyond 90%, Donegan says. “We did not start that way when we launched 12 years ago,” he acknowledges. “We have been lucky to work with visionaries who would do controlled releases or other tests to help us train and ground truth the algorithms. Today, if we detect a vehicle in a right of way; poor chemistry in the water; a tree that is likely to fall on a power line; a methane, oil or produced water leak; or a land movement, we are on the money.”

How It Works

The satellites that Satelytics uses have spatial resolutions as low as a foot by a foot, but Donegan says the company can often detect smaller problems by using proxies. “For example, when we monitor pipelines, we use vegetation alongside other surrogates,” he says. “We can do that because a minute drop of oil in the root system of trees, shrubs or grass will show up in their spectral signature.

“Our algorithms analyze the extended data from satellites rather than visual data. Specifically, we use the power of light shining on the earth’s surface and look in the infrared and shortwave infrared spectra. When light hits a healthy oak tree, it creates one pattern. If that oak tree becomes unhealthy, the pattern changes in predictable ways.”

To track how assets change over time, Satelytics’ platform retains all the data customers ask it to collect, Donegan says. If something unexpected occurs and a client needs to check past events for an area Satelytics is not monitoring, the company can sometimes purchase old data from satellite operators’ archives. “On many occasions, our customers have asked us to go back in time to help diagnose the cause of an issue or to determine when it began,” he says. “We have saved them millions of dollars by disproving the accusations behind lawsuits.”

Donegan stresses that Satelytics only provides information to clients in the industries it serves, including oil and gas producers, pipelines, utilities, miners and farmers. “I would have to be dead before I do any work for the government or a nongovernment organization that wants to embarrass the oil and gas industry,” he says.

Companies interested in using satellite data should start small, he advises. “We can provide the best information in the world, but it is meaningless unless a company has the field teams and processes in place to act on that information,” he explains.

As companies scale up and refine their programs, they often see remarkable returns, Donegan says. He cites Duke Energy, which has shortened its response time to methane leaks ten times over, significantly improving safety for its employees, customers and communities.

Over time, Donegan says most satellite users expand their coverage area, collect more frequent data over certain areas or tackle new problems. “We do not charge any extra to analyze the same set of data with multiple algorithms,” he remarks. “In fact, we encourage it, because it’s easier to justify renting a satellite if several departments benefit.”

The number of satellites in orbit has grown rapidly in the past few years, Donegan observes. “With the amount of money being spent above the Earth’s surface, we believe that by 2028 or 2030, the time between satellite visits for every place on Earth will fall to every few hours, if not multiple times an hour,” he divulges. “I like that, because it means companies can use satellite data to continuously assess high-risk areas.”

Vapor Recovery Units

At many companies, the attitude toward vapor recovery units has shifted, says Aaron Baker, vice president of compression engineering for Flogistix by Flowco. “They’re no longer an afterthought. Instead, they’re part of the initial plan when a facility is designed, which means we can engage early with the facility engineers to size the equipment appropriately.”

As companies deploy VRUs to protect the environment and comply with regulations, Baker says they get substantial economic benefits. “The rich gas that VRUs capture is three or four times more valuable than typical gas,” he says. “It generally pays for the VRU’s monthly rental cost in two or three days.”

Maximizing the economic and environmental benefits requires the VRU to not only run, but run well, advises Danny Burrows, the company’s vice president of software engineering. “A VRU can be reliable and available to turn on, but if it is slow to react to changes in the amount of gas it needs to compress, the site could still end up venting or flaring,” he says.

As scrutiny of emissions has risen, so has the value of vapor recovery units with enough automation to anticipate and adapt to changes in production. Thanks to clever redesigns, Flogistix says such automation is becoming affordable even on sites that handle lower production volumes.

As the EPA and some state regulatory agencies tighten restrictions on flaring, interest in VRU performance has grown, Burrows reports. “We have done the work to show that our VRUs are capturing the gas and pushing it down into the sales line,” he assures.

Expanding Access

Achieving reliable vapor recovery requires a precise, robust control scheme, Baker says. “Most of the locations we support have tank batteries, which are not designed to contain pressure,” he notes. “If the pressures get too high, the VRU must draw them down. However, if the pressure gets too low, oxygen could enter the tank and cause it to collapse.

“The pressure window is tight,” he says. “On one job in Nigeria, for a huge tank that could hold 250,000 barrels, the difference between the lowest and the highest allowable pressure was only 0.03 psi. Our VRU had to keep pressures in that window while dealing with fluctuations in the volumes coming into the tank, which meant it had to make multiple decisions every second.”

Historically, the hardware necessary for that type of automation has been too expensive to deploy on lower-volume wells, Baker reports. “For a long time, those wells have used small and simple VRUs that rely on a simple pressure switch to decide when to turn on or off,” he says. “They turn on when gas gets high enough to reach a certain level, stay on until they draw the gas below that level, and then shut off.

“This approach works, but with today’s scrutiny on emissions, even marginal wells with small emissions need smarter, more adaptable VRUs that can anticipate production surges and turn on early rather than reacting as they occur,” Baker says. “The challenge is figuring out how to provide such VRUs on a shoestring budget.”

Fortunately, smaller units can take advantage of cost-saving measures that would be inappropriate for their bigger brethren. “For example, the piping on a large VRU can be replaced with half-inch tubing that the fabrication team can bend by hand rather than welding,” Baker illustrates. He says other design changes allow the company’s line of economic VRUs to repurpose the heat generated during compression to achieve various goals, such as preventing liquids from dropping out.

To reduce costs even more, Flogistix manufactures these units in batches. Because each one has the same design, the fabrication teams can form temporary assembly lines, with each person handling specific tasks, Baker describes. “The economies of scale in this process are amazing,” he says. “They have helped us drastically cut the cost for a 15-horsepower VRU without compromising on the robust automation.”

Since introducing that VRU, Baker says the company has used a similar approach to develop 7.5 horsepower and 25 horsepower variants. The 7.5 horsepower unit handles 15 Mcf, the 15 horsepower one goes to 40, and the 25 horsepower unit doubles that to 80. “If you have five or 10 Mcf, the smallest unit turns down nicely and works well,” Baker says. “That is a big deal for operators who need a more efficient way to comply with regulations so they can keep marginal wells on line.”

Big Impact

Even at a lower cost, it can be hard to convince small operators with tight budgets to deploy a VRU unless they know it is economic, reflects Ali Sylvester, director of business solutions at Flogistix. “To quantify the economic benefits, we can look at a gas sample analysis from the well and estimate how much of the vapor is being vented or flared as methane or a heavier product,” she says.

The company also has invested considerable resources into accurately estimating the emissions that VRUs prevent, Baker adds. He says these reductions depend partly on how much gas flows through the VRUs. Since most VRUs lack flowmeters and it would be prohibitively expensive to retrofit them, the company uses data and machine learning to estimate flow.

“For more than a decade, we have been pulling in every data point we can from our units, even if we did not yet have a use for it,” Baker shares. “From that data, we know what the compressors are capable of and how much gas they should be moving in each scenario. This lets us match other data points with a likely flow rate.”

Those flow rates have reinforced VRUs’ value, Baker says. “Across our fleet, the amount of revenue we are returning and the emissions we are abating is astounding,” he says. “At one point, our VRUs were doing more to reduce greenhouse gas emissions than Tesla, based on the carbon dioxide equivalency value of the gas we captured compared with the same value of emissions avoided by an electric vehicle.”

Other Applications

The same data that allows Flogistix to derive flow rates is helping the company optimize its maintenance programs, Burrows reports. “Because we have collected data for so long, we have a treasure trove of information we can look at to train, analyze and validate AI models,” he says. “Those models compare data from the field with historical information and make recommendations. For example, they might detect that a VRU’s recycle valve is wearing out or notice issues with an engine’s performance, then share that information with our work order system.”

Baker says the problems that the AI reveals will require maintenance in some cases. However, others can be fixed remotely by adjusting settings.

Over time, Baker says Flogistix would like to collect even more data. “Today, our cloud-based platform polls units once every minute. That speed is almost unheard of in SCADA applications, but we could do even more by monitoring what happens during each minute and using machine learning to react in real time.”

With that goal in mind, Baker says Flogistix has developed a VRU control panel that acts as a hybrid of a traditional programmable logic controller and a PC. “Think of the panel as an industrialized, hardened computer that can also control machines,” he says. “Right now, we are redesigning some of our VRUs to take advantage of it. For example, we are building in flowmeters because those cost less when they no longer require a separate flow computer.”

Nitrogen Rejection

As U.S. LNG exports have grown, so has interest in nitrogen rejection units, reports Brennan Heiser, a senior process engineer with BCCK. “Nitrogen is an inert gas that negatively affects the burner, so few gas purchasers want it,” he says. “However, it is particularly problematic for LNG companies because it can cause tank rollover, a situation that can lead to dangerous pressure spikes inside the LNG storage tank.”

LNG exporters’ need for gas with low concentrations of nitrogen is helping drive increased demand for nitrogen rejection units, BCCK reports. The company says it is applying lessons from each installation to increase efficiency, reduce emissions and simplify operation.

To prevent that, LNG companies seek gas with nitrogen concentrations below 1%, much lower than the 3% or 4% typically allowed by interstate pipelines. “The other trend that is increasing demand for NRUs is gas processing in high nitrogen basins such as the Permian,” he says. “As wells in those basins mature, they often produce gas that contains even more nitrogen.”

In the last two to three years alone, Heiser says BCCK has built seven NRUs. “By improving the design to maximize efficiency, we have been able to reduce these units’ methane emissions to some degree,” he says. “Those improvements involve optimizing the hydraulics in the plant, adjusting the line sizes to avoid wasting power, and minimizing pressure drop in various areas to get as much out of the plant as possible.”

BCCK has developed a plant design that can achieve even lower methane emissions at the relatively marginal cost of some additional compression. If lower emissions become necessary to avoid fines from the EPA or other regulatory agencies, Heiser predicts this ultra-low-emissions design will gain popularity.

While building and supporting plants, Heiser says he has noticed that many of the plant operators are new to the industry with no processing experience. “To meet the growing power demand across the United States, more gas plants are being built, which means the industry needs more operators,” Heiser says. “It’s common for a plant to be run by former teachers, mechanics or construction workers who are ready for a new career.”

According to Heiser, that trend has reinforced an already compelling case for strong customer support and robust control schemes. “It is easy to develop schemes that work on paper and perform fine when the process is steady, but a good control scheme works when an upset occurs upstream or downstream of the equipment,” he stresses. “If a lightning strike or a fire at a compressor station shuts in half the field, the volumes, temperatures and pressures at the plant’s inlet can swing wildly. Even so, the plant still needs to keep its output on spec so the pipelines and regulators stay happy.”

With the right automation, Heiser says NRUs can show remarkable flexibility. “Shortly after a recent startup, the cryogenic plant that included one of BCCK’s NRUs changed from ethane rejection mode to recovery mode while the NRU was online. That altered the inlet composition from almost no ethane to about 10% ethane and a little bit of propane, but we anticipated this scenario when designing the NRU, allowing it to maintain product spec throughout,” he illustrates.

Central Control

In the long run, Heiser envisions operators managing multiple plants from central offices. To maintain process safety and integrity, remote operations will require significant investments in cybersecurity, Heiser acknowledges. However, he muses, the payoff may justify the cost and risks associated with connectivity.

“In college, I had a chance to tour air separation plants. Almost all of them were fully automated, with control rooms in an office building located in a popular city,” he says. “That setup makes it much easier to attract operators and to pass knowledge from seasoned hands to novices. Because each person oversees multiple plants, it’s also easier to apply best practices across facilities.”

This model does have limitations, Heiser allows. “Gas plants are close to the wellhead and see some dirty streams,” he clarifies. “There is a lot of manual cleaning that needs to take place, so they will always require someone to visit.”

Robust Design

The right design can minimize the chance of issues, Heiser reports. “I’m proud of the changes BCCK is making to its designs,” he says. “We are developing plants that are more efficient, more affordable and easier to control, and we continue to learn and improve.

“As part of our optimization efforts, we have focused on every aspect of the NRU, from the cryogenic side to the compression and oil filtration. On the oil filtration skid, we have added check valves in strategic locations, eliminated bypasses and enhanced the automation to prevent oil from getting into the system.”

The company has also simplified its compressor automation. “When I started at BCCK in 2022, one project had seven automated controllers on the inlets and outlets of the compressors,” Heiser recalls. “Today, we are down to two per compressor, which greatly simplifies operation and improves reliability.”

As the need for NRUs has grown, Heiser says BCCK has gotten more involved in assisting customers with decisions they once handled internally. He points to compression as a common source of issues early in a plant’s life. “Customers know compression and prefer to buy it themselves based on specifications we provide for the flows and pressures coming into and out of the plant,” Heiser says. “In the past, they would also decide how the compression is arranged and design the surrounding systems.”

Over time, Heiser says BCCK has seen customers try arrangements that would make sense in other applications but cause issues with NRUs. “To prevent those issues, we now design the systems around the compressor, then inspect them on site to ensure they are installed properly,” he says. “That extra guidance has eliminated some early headaches for customers and helped us cut the startup and commissioning time for new units in half.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.