Latest Startups Aim To Revolutionize Industry With Advanced Technology

By Colter Cookson

For a new upstream service and supply company to do well, it needs to differentiate itself from the companies its customers already use.

Many of the newest startups say they will achieve that goal by combining exceptional service with products and business models that significantly reduce customers’ costs. These products and services include affordable pump components, locally sourced proppants, and tools that enable operators to analyze every completion during field development. Other startups offer leasing software that automates error-prone calculations, advanced chemistries that penetrate far into the formation, remote monitoring affordable enough for stripper wells, and managed pressure drilling equipment that is easy to use and maintain.

The executives behind these startups say they are after more than money.

“Like most of the people on my team, I have been in oil and gas for a long time,” notes Chris Buckley, founder, president and chief executive officer of ST9 Gas + Oil. “We want to leave a legacy, and to be remembered as people who helped transform the industry into one that operates more efficiently.”

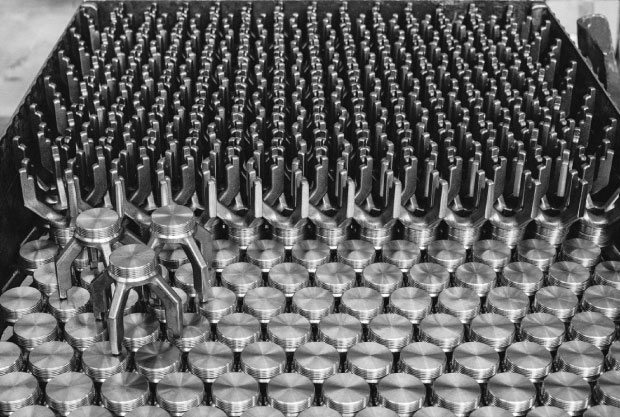

Buckley says his team hopes to address the second-biggest expense after diesel associated with owning a hydraulic fracturing fleet: buying and maintaining pump components such as fluid ends, valves and seats, and packing. “Our goal is to develop pumps and pump components that will have a lower total cost of ownership,” he outlines. “To do that, we identify the best products available on the market, and then set ourselves the challenge of finding ways to do things even better.”

The company started by looking at valves and seats. “We set a goal of reducing the initial cost to 35 percent lower than the industry standard,” Buckley recalls. “When we got into the field, we discovered that our design also beat the best alternatives’ service life by an average of 33 percent.”

These valves and seats are the first of many products ST9 Gas + Oil plans to introduce to reduce the cost of maintaining pressure pumping fleets. According to the company, the valves and seats last longer than other best-of-breed designs but cost 35 percent less.

To achieve that durability, ST9 uses a forged top rather than casting and urethane with advanced chemistry that improves its performance, Buckley relates. “The valve is the only one in the industry that uses screw-in legs. This let us come up with a manufacturing process that would create a product with great reliability but was simple enough to reduce costs,” he says.

According to Buckley, the valve and seat has been used throughout North America, including the Eagle Ford, Permian, and Marcellus in the United States and Western Canada’s Duvernay Shale. In every field, he says ST9’s products have outperformed traditional designs.

Buckley points out that in the first six months of its existence, ST9 Gas + Oil (a name that the company says deliberately inverts “oil and gas” to convey its commitment to change) filed for eight provisional patents. He says the company will continue to innovate by investing at least 70 percent of profits in research and development, and drawing on ideas from outside the industry and collaborating with suppliers to optimize manufacturing processes.

“The valve and seat is only the beginning,” Buckley enthuses. “We have a new range of fluid ends coming out at the beginning of 2018 that should reduce operating costs 15-20 percent. We also have electric and mechanical power frames and transmissions in the works.”

Buckley predicts these products will provide huge savings to well servicing companies. “For a medium-sized well servicing company, we can reduce operating costs by $3 million-$7 million a year,” he calculates.

Permian Basin Sand

Geologist and serial entrepreneur Ben M. “Bud” Brigham, chairman of Brigham Resources LLC, is attacking well completion costs from another angle. In partnership with other seasoned oil and gas producers as well as sand mining experts, he is launching Atlas Sand, a sand mining operation in the Permian Basin.

“Quality fracture sand is integral to the Permian Basin’s success,” Brigham says. “Because much of that sand comes from outside the basin, transportation accounts for 60-75 percent of its cost. We formed Atlas to provide local sand, which presents a remarkable opportunity to reduce completed well costs and enhance reliability for all Permian operators. In fact, analysts estimate it could reduce completed well costs by 5 percent.”

Local sand is a great fit for modern completions, Brigham assures. “The quality of our finer grades is right up there with Northern White,” he says.

Atlas Sand is building sand processing plants at open sand dunes near Kermit, Tx., and Monahans, Tx. According to Brigham, these locations represent the northern and southern ends of the sand fairway.

To reduce Permian Basin operators’ proppant costs, Ben M. “Bud” Brigham has launched Atlas Sand, which he says will produce high-quality sand from West Texas sand dunes. The Atlas team includes (from left to right) Chief Financial Officer John Turner, Chief Operating Officer Hunter Wallace, Vice President of Sales and Marketing Matt Stafford, Chairman and Founder Brigham, Plant Manager Brian Vinson, Vice President of Operations Tim Stauffer and Plant Maintenance Manager Cliff Anderson.

“The open dunes have experienced thousands of additional years of Mother Nature’s natural winnowing and processing, which has given the sand top-tier sphericity and premium crush strength,” he adds. “Without any overburden, soil development, organics or associated impurities, our yield and operating costs will be top tier.”

Atlas’ Permian reserves contain both 100 mesh and 40/70 grades, matching up perfectly with what most Permian operators need to optimize well performance, Brigham states. He says the Kermit plant should come on line in the second quarter of 2018, with Monahans following in the third quarter. Each will have an initial capacity of 3 million tons a year, but in 2019, Atlas plans to expand both to 6 million tons. “Our reserves are vast enough that we can add more plants over time as demand grows,” Brigham says.

The company’s plants employ a unique design, he says. “The plants include redundancy that will improve safety and should almost eliminate downtime, so we will be able to produce at our permitted capacity,” he assures.

The plants are situated ideally to deliver sand to Permian customers at a low cost, Brigham continues. “The Kermit plant is bisected by two highways, and the traffic studies we have done suggest we will be able to get trucks in and out even if all the nearby sand mines max out,” he says. “Monahans is in an even better position. It is adjacent to two highways, including I-20, a major thoroughfare, and near a railroad.

“We are the only organically generated Permian Basin sand mine, built by Permian operators for Permian operators,” Brigham remarks. “Because we are funded by internal capital and strategic investors, we have the freedom to build a company to last.”

Brigham says the company eventually may go public, which means it must exercise extreme diligence in every area, from accounting and reserve audits to environmental stewardship. “We will be aggressively and smartly reclaiming mined lands, avoiding optimal dune sagebrush lizard habitat, and having substantial set-asides,” he details.

Completion Quality Control

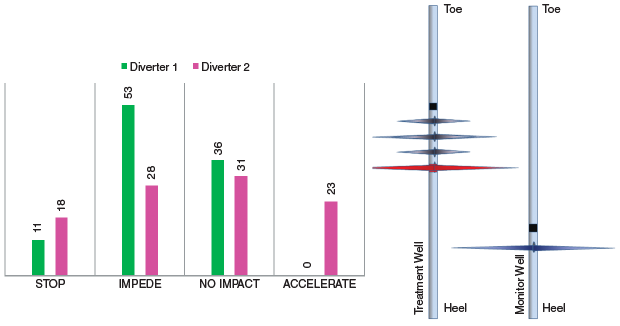

What if operators could map every development well’s completion to determine whether it is performing as expected or should be changed to match varying geology? According to Reveal Energy Services, that now is a technical and economic possibility with a pressure gauge on a monitor well. Using technology licensed from Statoil Technology Invest, the startup applies the recorded pressure response in the monitor well to calculate a fracture map of the newly created fractures in the treatment well.

Reveal Energy Services says it uses the pressure data to:

- Quantify 3-D fracture maps of half-length, height and asymmetry;

- Determine how far proppant has been placed within the fracture;

- Understand whether a diversion technique is working;

- Know if the fluid is distributed between multiple clusters; and

- Identify the depletion boundary surrounding a parent well.

“Pressure-based fracture monitoring enables 100 percent fracture assurance,” says Sudhendu Kashikar, the company’s CEO. “Because it only requires a pressure gauge on a nearby wellhead, it is simple to deploy. Although it is as accurate as legacy completion evaluation methods, the cost is typically less than 20 percent of those methods.

Reveal Energy Services says its pressure-based fracture maps enable operators to validate their completion design on every well in several ways. In this example, the monitor well, far right, evaluated the effectiveness of individual diverter drops for two diverter types. Diverter 1, the better choice, stopped fracture growth in 11 percent of the drops, impeded fracture growth in 53 percent, and had no impact in 36 percent.

“The low cost, accuracy and ease of deployment mean this technology can be applied on every well to act as a form of quality control,” Kashikar continues. “By providing a near real-time assessment of a completion, it allows operators to adapt to geological variations that occur throughout plays and to the gradual changes in stress profiles that occur as plays are developed, reducing geologic and financial risk.”

The pressure data can be processed quickly enough to inform decisions mid-completion, Kashikar mentions. “For example, after the first stage is completed, we can look at the diversion technique used, make changes for subsequent stages, and get rapid feedback on whether those changes improved performance,” he reports.

The rapid feedback allows operators to test multiple completion ideas and zero in on the one that is most effective, Kashikar adds. “A customer interested in evaluating diversion techniques might deploy one in the first four stages, then modify the technique or switch to another based on our feedback,” he says. “By the end of the pad, the customer will be able to evaluate two or three diversion materials and techniques, and identify the combination that gave the best results.”

The physics that turn surface pressure measurements into details on fracture geometry, proppant placement, diversion effectiveness, cluster efficiency and depletion boundaries are complex but proven, Kashikar asserts. He says Reveal Energy Services has validated its results by comparing them with ones from other technologies, such as microseismic and distributed acoustic sensing/distributed temperature sensing.

“This pressure-based fracture map technology has worked extremely well in every project where it has been applied,” he reports. “We have deployed it on almost 1,500 stages across seven basins in the United States and Canada, including the Permian, Eagle Ford, STACK/SCOOP, Woodford, Marcellus and Bakken. Every customer that has used it has continued to use it.”

Tiny Production Booster

Phoenix Chemical Technologies spent eight years refining a suite of chemicals containing an extremely small tetrahedral silicate monomer that boosts production by weakening surface tension between oil and rock, relates Shawn Kurtz, Phoenix’s founder. He attributes much of the service company’s success to the monomer, for it made Phoenix’s flagship paraffin inhibitors extremely effective.

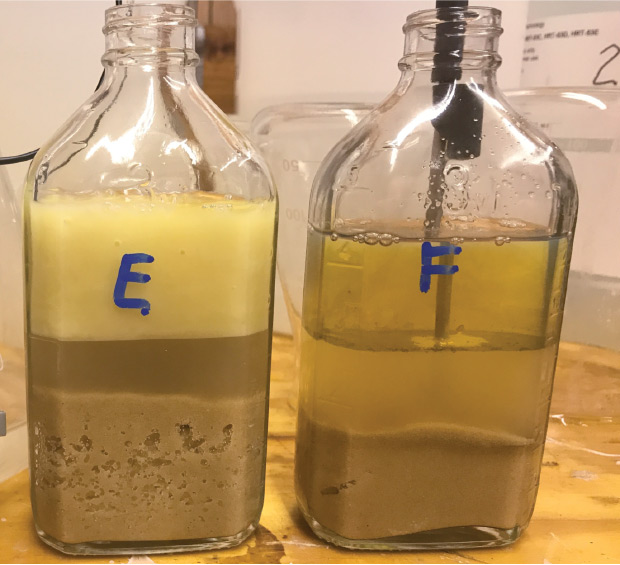

Through a new company, Mako Chemicals & Services, Kurtz says he is distributing chemicals containing the monomer to the industry. Because it dislodges oil and leaves behind a coating that reduces friction and protects metal from corrosion and scale, he says the monomer can enhance friction reducers and scale, corrosion and paraffin inhibitors.

“The monomer reduces friction like a surfactant but has none of the adverse effects,” Kurtz reports. “Because it is inorganic rather than organic, it does not create emulsions or leave residuals that restrict production by plugging pores. This simplifies chemical programs by eliminating the need to follow the treatment with others that exist solely to deal with emulsions.”

According to Kurtz, the monomer has two other advantages. First, it is green. At a customer’s request, Kurtz says he can get a product that uses the monomer certified by NSF, an organization that develops and enforces health, safety and environmental standards for a variety of products, including water treatment chemicals and food-grade lubricants. Kurtz points out that a green certification from NSF would eliminate the need to report chemical spills.

Mako Chemicals & Services’ products often contain a tiny tetrahedral silicate monomer that reduces friction, mobilizes oil, dislodges paraffin, and prevents corrosion and scale. Unlike comparable products (left), the company says the monomer (right) works without leaving behind formation-plugging emulsions.

The friction-reducing monomer also penetrates far into the formation, Kurtz says, citing two mechanisms. First, with a size measured at the femto scale, it is even smaller than nanotechnology and therefore capable of moving through tiny pore spaces.

“In addition, the monomer moves on its own by affecting an ion exchange,” Kurtz says. “When it encounters hydrocarbons, its negative charge causes it to penetrate them and eject any water they contain. In effect, the monomer swaps places with oil, dislodging the oil while moving into the formation faster and farther than the water that carries it.”

In one field test, a mixture containing the monomer went at least 86 feet into the formation, he says. In another test, the monomer was injected into a steam injection well that had been unused for three months, then chased with freshwater. In only two days, Kurtz says the operator noticed higher water pHs in production wells 13 acres away, a testament to the monomer’s mobility.

The same test showed how much the monomer’s ability to dislodge oil and leave behind an oil-repelling coating boosts production, Kurtz comments. “Within 24 hours, oil production from the production wells tripled or quadrupled,” he details.

In 15 Austin Chalk wells, monomer-enhanced chemistries increased production by as much as 225 percent, Kurtz continues. He reiterates that the coating the monomer leaves behind protects against scale, corrosion, and paraffin.

Kurtz says the monomer can be applied when performing near wellbore cleanups or stimulating old wells. “It can also be used as part of water, steam or carbon dioxide floods, as well as in completions on new wells,” he reports.

“If we can get this technology into the corrosion and scale inhibitors used in completions, every bit of slickwater will become a carrying agent for it. It may be able to increase recovery from the fracture network from 35 percent to 75-85 percent,” he estimates. “At the same time, it will simplify chemical deployment by reducing the need for other corrosion and scale inhibitors.”

Lease-Speeding Software

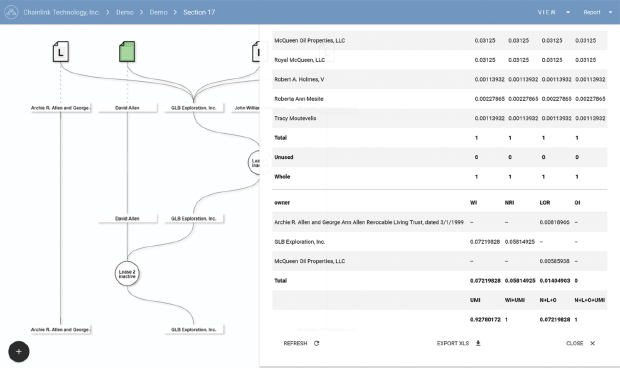

Tracts.co aims to use automation to cut in half the time landmen and title attorneys spend on projects, says Ashley Gilmore, the company’s co-founder and CEO.

“Normally, landmen gather instruments and take notes to create run sheets, ownership reports and flowcharts,” Gilmore describes. “With our cloud-based software, Tracts, they only need to enter the instruments. The software automatically builds the run sheets, ownership reports and flowcharts.

“In the Permian Basin, we have a client who says this automation has cut two or three weeks off every six-week project,” Gilmore reports. “In Oklahoma, we had a $10 billion client do a direct comparison between Tracts and two control sections using traditional methods. Tracts took four days, compared with 18 and 19 days.”

By allowing landmen to focus on interpreting and entering one document at a time, the software also improves accuracy and validity, Gilmore adds. “In the past, each landman would have to determine whether hundreds of other instruments relate to the one they are looking at, understand those relationships, and remember several tiny percentages in order to perform complex calculations,” he says.

With Tracts.co’s flagship software, landmen no longer need to worry about building flowcharts, creating reports and performing complex calculations. Instead, they can focus on interpreting and entering individual instruments. Tracts says this cuts project times in half while preventing potentially costly title defects.

To convey how complex those calculations can be, Gilmore mentions that Tracts has to consider 12-18 dimensions to build its flowcharts. These include the time, the parties, who has surface and mineral interest, and what type of interest each person has. Gilmore points out that mineral interests alone are divided into five rights: executive, bonus, delay, ingress, and royalty.

With so many details to keep track of and calculations to perform, it is easy for landmen and title attorneys to make mistakes, Gilmore warns. He references a University of Utah study that analyzed the results of title cleanups after acquisitions. It found that title defects resulted in a net acreage loss around 19.9 percent. In other words, almost one in five acres were affected by title defects.

Gilmore says Tracts can address subtle mistakes that lead to such defects. “With certain interests, it is impossible to tell whether they have an impact until all the title has been run, including the lease being taken, so the landman has to backtrack through each title to determine if there has been any overconveyance,” he says. “Tracts does those calculations, so it will flag the overconveyance immediately.”

The software also can spot more mundane mistakes, such as duplicate grantors, Gilmore says. Because it builds and displays the flowchart as instruments are entered, it can also help landmen and title attorneys notice potential issues. For example, if an unusually lengthy period of time has passed between instruments, the landman may see the gap and realize an instrument is missing.

Gilmore says Tracts’ interface is simple enough that even less technically-inclined landmen gain 95 percent proficiency in a day or two.

To understand the relationship between instruments and perform calculations correctly, the software relies on a proprietary algorithm. “We have run thousands of test cases to make sure it comes up with the right answers.” Gilmore reports. “Even when we try to break the software with cases so complex they will never happen in real life, Tracts comes through with flying colors.”

Affordable Remote Monitoring

To give stripper well operators access to remote monitoring, Strode Pennebaker formed Sensorfield LLC and worked with Rice University engineers to develop small, solar-powered sensors that are affordable, easy to install and durable.

Sensorfield provides sensors capable of gathering all key oil field measurements, Pennebaker says, including tank levels, pressure data and flow rates. He adds the sensors also monitor parameters for beam pumps and compressors.

“The sensors are as easy to install as refrigerator magnets,” Pennebaker enthuses. “Each sensor is a small box with a high-powered permanent magnet and a button. A pumper takes the sensor to the field, sticks it on a tank, line or pump, and presses the button to turn it on. The sensor automatically finds and connects to the nearest gateway, which sends the data it collects to the cloud through cellular networks.”

Operators access that data through a smartphone or computer, Pennebaker notes. Because the sensors require no configuration or maintenance and lack the screens, interfaces and supporting infrastructure associated with traditional SCADA systems, he says they are much more affordable. “Our system generally costs less than a third as much as current systems,” he details. “The self-installation also gives operators the ability to control and customize sensor placement.”

To bring the environmental and efficiency benefits of remote monitoring to stripper wells, Sensorfield developed compact, solar-powered sensors. Because they install as easily as refrigerator magnets and automatically configure themselves, the company reports its sensors cost a third as much as traditional SCADA systems.

The sensors have an extremely high resolution, Pennebaker adds. “For example, the standard for reporting oil tank levels is a quarter of an inch, but our tank level sensors have 10 times higher resolution,” he says.

For most operators, Pennebaker admits that high resolution seems unnecessary. “In general, our customers buy the sensors to know when a tank is about to overflow or pressures are getting out of range,” he says. “That can be achieved with less precise sensors. However, we know from experience that operators will find other ways to use the data if they have sufficient resolution.”

To illustrate, Pennebaker points to Trek AEC, a Kansas operator. Trek used wellhead pressure data to forecast and schedule chemical remediation and injection well filter changes. By watching small changes in beam pump stroke times, Pennebaker says, Trek can easily detect the pump-off time, allowing it to optimize its time clocks. In another case, a 20-millisecond change in a beam pump’s speed led Trek to investigate a well and identify iron sulfide being produced in the well fluids. This enabled treatment before the iron sulfide became a major issue.

Trek AEC’s use of the sensors extends to sensitive environmental areas. In nearly every case where sensors were installed and early warnings heeded, the operator says potential clean-up costs would have exceeded the cost of the sensors.

Sensorfield has deployed its sensors in California, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. They endure extreme temperatures and consume so little power that their tiny built-in solar cells work even in shady locations or areas with long, cloudy winters, Pennebaker assures. He says the sensors even have survived hurricanes.

“They have the occasional problem. One time, a cow chewed off a cable,” Pennebaker allows. “However, when a sensor breaks, we detect it and let the operator know. Then we pack up a replacement and overnight it to the operator with no questions asked. Alternately, our larger customers carry extra sensors in their trucks so their pumpers can swap out or add sensors anywhere.”

Pressure Control Equipment

High-pressure managed pressure drilling (MPD) is becoming increasingly important in the Permian Basin, says Charlie Orbell, a 35-year drilling industry veteran who now serves as president of ADS Services LLC.

By providing effective and affordable pressure control equipment, ADS Services aims to help Delaware Basin drillers employ managed pressure drilling. The company expresses pride in its safety record and its equipment, which is designed for easy maintenance and operation.

“As operators move into the Delaware Basin and drill deeper wells, they are encountering higher pressures. Because of interference from nearby completions, they also are seeing pressure profiles that differ from what they expect. MPD allows operators to adapt to pressure changes quickly, so it is becoming more common,” Orbell says.

To provide the equipment needed to enable high-pressure MPD, Orbell and Black Bay Energy Capital created ADS Services by recapitalizing Air Drilling Solutions, a Permian Basin company Orbell notes had long provided low-pressure MPD equipment.

“The company has an experienced, loyal workforce that has a great safety record and a name for providing reliable equipment,” Orbell praises. “Its focus on safety and strong customer relationships make Air Drilling Solutions a great foundation to build on.”

By expanding into high-pressure MPD and pressure control equipment, Orbell says ADS hopes to double in size. “We recapitalized in June, but we already have deployed equipment on three rigs in the Delaware Basin,” he reports.

Orbell says the company is using top-of-the-line, high-pressure rotating heads made in the United States and certified to API 16 RCD. “These heads use a modern design,” he praises. “Recognizing that traditional designs are extremely complex, the engineers started with a blank sheet of paper. They looked for ways to simplify the design and make it as easy as possible for field hands to maintain and operate.”

While it may eventually expand into other basins, Orbell says ADS is moderating its growth to ensure it properly trains its employees. “We are big believers in taking the time to find the right people and promoting from within,” he comments. “That will help us keep the culture of safety and service that has made our predecessor so successful.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.