Mexican Oil Reform

Mexico Opens Initial Bidding After Amending Constitution

By Adrian Lara

NEW YORK–Following the December 2013 passage of constitutional amendments required to reform the energy sector and subsequent secondary legislation, the Mexican government has opened the oil and gas sector to outside investment. There are now various structures of possible contracts, such as royalty-and-tax licenses, production sharing agreement (PSA) contracts, and profit-sharing contracts in addition to limited service contracts, which were previously the only option.

Price-based royalties and exploration rental fees are payable under all contracts and assignments except service contracts, and all exploration and production companies–including the national oil company, Pemex–must pay both a hydrocarbon activity tax based on the contract area and an income tax as great as 30 percent of net profits.

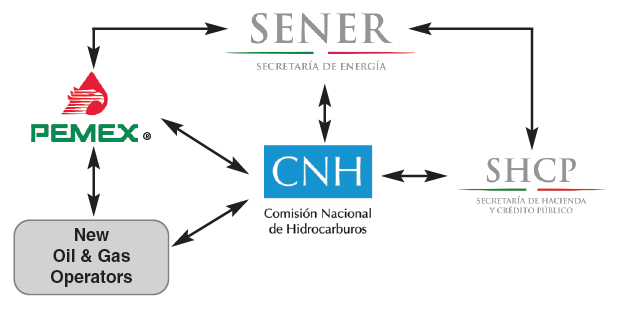

Because the reform has redefined the sector’s institutional arrangement significantly, Pemex has ceased to be the main contracting agent on the side of the Mexican government. Under the new oil and gas administrative structure, the Ministry of Energy (Sener) is the main coordinating agency. Together with the National Commission for Hydrocarbons (CNH), Sener is in charge of selecting contractual areas, contract design, and bidding guidelines. CNH has been strengthened and given greater technical autonomy, and is now directly in charge of organizing the bidding rounds.

The Ministry of Finance (SHCP) is in charge of assessing the fiscal terms, and therefore plays a significant yet indirect role by influencing the attractiveness of the areas offered to participants. As shown in Figure 1, these are the primary agencies overseeing oil and gas investment in Mexico, but new institutional actors include an agency created to oversee environmental and safety regulations, and a fund that will be in charge of paying contractors and managing state oil revenues.

However, as evidenced by the ongoing first bidding round, participants’ main point of contact is CNH. The commission is in charge of organizing the data rooms, reviewing each company’s qualification process, conducting the bidding round, and awarding and signing contracts. It also will be in charge of the technical approval of exploration and development plans, authorizing surface exploration and well drilling, and managing contract auditing.

These are not small responsibilities for an agency that has been around only for few years, that is still building its technical cadres and expertise, and for which its role as a regulatory body has meant some degree of confrontation with Pemex.

The fiscal regime applied to Pemex also has been changed. During 2014, the Mexican government received a formal request from Pemex consisting of a list of assets that it wished to keep under its ownership. This process was dubbed “Round 0” and resulted in Pemex being assigned 83 percent of the country’s proved and probable oil reserves and 21 percent of all prospective resources. The awarded areas are called entitlements, and in the future, Pemex could request that Sener and CNH carry out a feasibility assessment to approve farming out selected entitlements. The definition of the fiscal terms of these types of joint operating agreements will be established by SHCP.

First Bidding Round

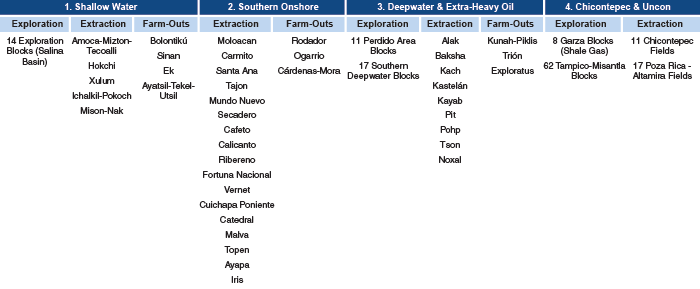

In line with the schedule offered in mid-2014, the first bidding round has begun. It was split originally into five main phases that were scheduled to offer areas in the following order: offshore shallow water, extra-heavy oil, the Chicontepec Basin onshore region (home to an estimated 40 percent of Mexico’s hydrocarbon reserves) and unconventional (shale and tight oil), other onshore areas, and deep water.

The government previously had released an ambitious timeline that would have seen the bidding for shallow-water areas opened in the first half of November 2014, and for the four other areas in each of the first halves of the following four months. In reality, the call for bids has been delayed for every scheduled phase and it is possible that some producing fields and exploration blocks in the unconventional areas have not been offered because of their low attractiveness in the prevailing oil price environment. The complexities associated with CNH organizing its first bid round also will account for some of the change to the timeline (Figure 2).

It is important to note that in addition to the extraction (production) and exploration areas, the round is synchronizing the first farm-out areas in which Pemex is looking to establish partnerships in producing or exploration assets. These would include assets in all of the different areas considered for round one (i.e., shallow water, onshore, extra-heavy, deep water, and unconventional).

The importance of how these farm-outs actually are concluded in the initial round lies in signaling how attractive future farm-outs will be to interested operators. Pemex’s new fiscal regime aims to lower the government take of net profits from 78 percent to 65 percent over the next five years. However, the government take is not yet radically different from previous years, and in this context, Pemex has an interest in participating in the relatively more attractive terms of the new contract schemes.

As of mid-April, CNH still needed to do the call for bids on onshore assets (expected by late April or early May), deep water and extra-heavy crude oil assets (possibly June), and unconventional assets (no indication of a date so far). For the shallow-water assets, CNH has scheduled the release of final contract terms for exploration blocks by May 29 and the bidding deadline by July 15, and for shallow-water discovered assets the release of final contract terms by Aug. 14 and the bidding deadline by Sept. 30. It is likely that the bidding deadlines for the other areas will extend until late 2015 or even into early 2016.

Investment Attractiveness

In general, the investment attractiveness of the areas offered in round one depends on a combination of the geological nature of the type of resource, the cost of exploration and development, and the applicable fiscal terms. In the immediate term, low oil prices weigh in significantly. In this context, it is relevant to examine how round one is designed because it provides some margin of maneuver for the state. The series of five stages allows the government to receive feedback from participants and adjust contract terms before final bidding for each area takes place. Each phase can choose between four types of contracts, but it seems that in practice, the options come down to whether to offer areas under PSAs or royalty-and-tax licenses, which are two of the most common schemes in the industry.

Accordingly, the government could incentivize the extra-heavy crude oil, deep water or unconventional areas by using a royalty-and-tax license scheme. In addition, for the first shallow-water phase of round one, the government has placed a restriction on the partnerships that can be formed so larger companies (those with daily production in excess of 1.6 million barrels of oil equivalent) cannot form a consortium. This was done partly with the intent of increasing competition among big international oil companies, but it has been indicated that such restrictions will not exist for other areas, such as deep water.

However, the government will set a minimum bid value in deep water, which basically indicates the minimum payment to the state, and this will be set when the final bidding terms for each phase are published. This could be a discouraging signal if participants assess this floor to be too high.

Production Sharing Contract

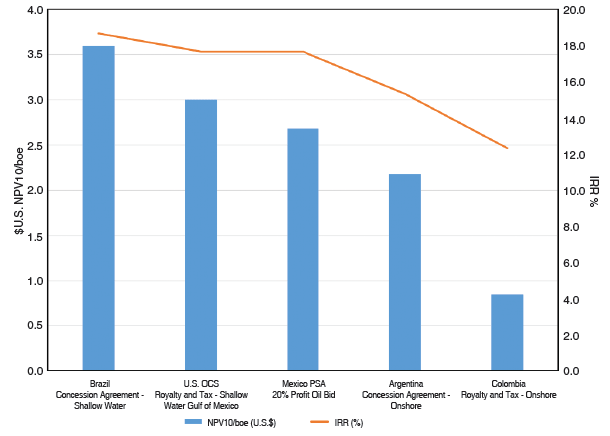

The shallow-water blocks and fields are located near infrastructure and are expected to have a production cost below $20 a boe with potential production of light crude oil. A comparison of the regime with applicable shallow-water areas in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico and other Latin American nations suggests that bids offering the government an initial 20 percent share of profit oil may be competitive (Figure 3).

While the regime appears relatively responsive to low oil prices and some assets could remain profitable at $50 oil up to a bid of 30 percent, the profitability of a PSA contract might be challenged at $40 oil. The final value of the biddable parameter determining the state’s initial share of profit oil will be a significant determinant of the attractiveness of Mexico’s production sharing contract regime.

The extra-heavy oil fields in shallow water also set for bidding could appear less attractive than other discovered shallow-water fields because of the significant price discounts associated with their low-quality crude. To date, CNH has indicated that the contract type for extra-heavy oil projects will be the same as the one applicable to the deepwater exploration blocks (royalty-and-tax). For deepwater areas, it is expected that the government will offer royalty-and-tax licenses, reflecting the high costs and risks associated with deepwater exploration and development.

The onshore assets in round one include both extraction and exploration areas. Some of these are conventional producing fields located in the southeast of the country and some are unconventional areas in Central to Northwest Mexico, not far from the Gulf Coast. However, the onshore area with the largest proved, probable and possible reserves is located in the Chicontepec Basin. With approximately 7 billion boe in estimated resources, Chicontepec is thought to require continuous drilling to increase and sustain production, similar to unconventional resource play development methods.

For the unconventional exploration block, there is an additional negative aspect in that some of these areas lack the infrastructure of other onshore areas (mainly pipelines), making them unlikely to be profitable at current price levels. In this context, there is not much that the government could do to improve attractiveness, and although data room access could be made less costly so that smaller independent companies have an incentive to participate, the unconventional assets are perceived as the most disadvantageous phase of round one.

Shallow-Water Phase

With the drop in international crude oil prices, some of the areas considered in round one do not appear as attractive as they did at the end of 2013. Moreover, with the first PSA terms published for shallow-water blocks and fields, it seems that operators consider the fiscal terms too harsh because the built-in adjustment mechanism favors the state whenever there is an upside in revenues.

Furthermore, the government is expected to set a minimum in the bid parameters to indicate the level that the state would consider the lowest acceptable share of profit. If this lower limit is set too high according to the operators’ economic analyses, a scenario of few bids (or no bids at all) could materialize.

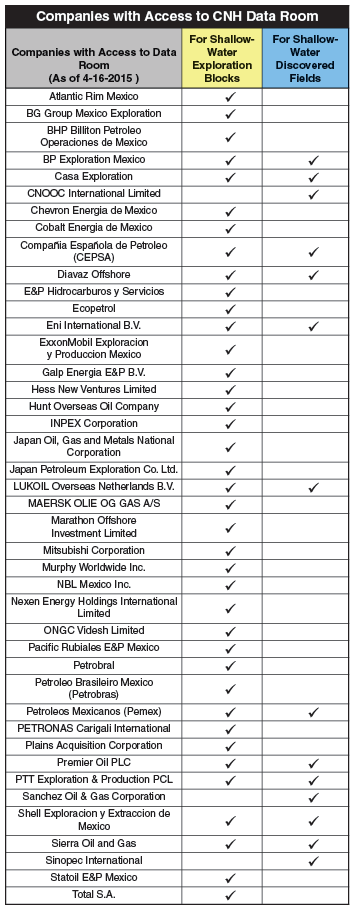

So far, there has been noticeable interest from oil and gas operators in the shallow-water phase of round one. Table 1 shows companies with access to CNH’s data room as of mid-April. There is a representative sample of big IOCs and medium-sized companies, including independent operators. It is true that proximity to U.S. oil and gas markets and the U.S. service and supply sector makes the current and future offered areas attractive in a medium- to longer-term perspective. However, even this does not guarantee competitive bidding, and therefore nothing can be said yet about the success of round one.

A significant amount of political capital has been invested in getting to round one, from having the three main political parties agree in Mexico’s congress to a major change in the constitution, to passing the secondary legislation and redesigning the sector’s institutional organization.

Furthermore, the administration has experienced some legitimacy issues that have lowered its approval ratings and public opinion at the expectation of the next negative result from the government. In this context, there is clear interest in the administration for round one successfully receiving bids and awarding most of the offered areas.

In addition, any possible changes to the upstream fiscal and regulatory regime in Mexico are likely to depend on how attractive the contracts in round one prove to be and the exploration results in the blocks that are awarded. If bidding is competitive in round one and significant discoveries are made, the government may offer tougher fiscal terms in future rounds. In contrast, poor exploration results and lackluster participation likely would spur the government to offer more attractive terms.

ADRIAN LARA is senior upstream analyst, Americas, at GlobalData Energy in New York. He directs the team in charge of conducting quantitative and qualitative research on upstream oil and gas activities in Latin America. Lara has several years of experience as an oil and gas industry analyst, and previously held positions within the trading arm of Pemex, where he focused on analyzing oil and gas fundamentals related to upstream export strategies and international trading. He also was a visiting research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, where his research focused on Western Hemisphere oil supply scenarios. Lara holds a B.A. in economics and political science from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México and an M.S. in mineral and energy economics from the Colorado School of Mines, with a specialization in oil and gas from the Institut Français du Pétrole.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.