Modern Frac Fleets Deliver Wells Faster And Consume Less Fuel

By Colter Cookson

“Waste not, want not” has become the hydraulic fracturing industry’s motto. Modern fleets do everything possible to minimize fuel consumption, simplify surface equipment and automate routine tasks. In the process, they are discovering ways to increase horsepower density and complete wells with fewer people. These innovations cut operating costs while reducing safety risks, community impacts and emissions.

Many of the companies behind these improvements say they have benefited from vertical integration. In-house manufacturing has helped them blunt the impacts of global supply chain disruptions. Even so, those disruptions have reinforced broader trends that limit how quickly new pressure pumping fleets can come on line.

“The demand for pressure pumping services exceeds supply,” assesses Matt Wilks, PF Holdings’ executive chairman. “In the past, the demand may have led service companies to build too many fleets, but I don’t believe that will happen today because operators, service companies and investors have become more disciplined. Investors used to be more aggressive about giving capital to companies with contracts. Today, they look more closely at how new capacity will affect the macro environment and deploy capital only when it makes sense.”

The spreads that are built tend to be electric or dual-fuel fleets. “The goal is to displace diesel with natural gas,” Wilks explains. “The delivered cost for diesel runs around $5.50 a gallon, and an all-diesel fleet consumes 7 million-10 million gallons a year, which puts annual fuel costs between $3.85 million and $5.00 million. A single Mcf of gas can displace about eight gallons of diesel, so electric or dual-fuel fleets can deliver incredible savings.

“The economic incentive for dual-fuel and electric fleets is strong enough that, eventually, we do not think we will see many all-diesel fleets,” Wilks predicts. “Diesel fleets will handle single well pads and some recompletions, but completing multiwell pads will be done by some form of fuel-efficient fleet, whether it’s an electric fleet that runs entirely on natural gas or a dual-fuel fleet with high substitution rates.”

Wilks points out that on Nov. 1, ProFrac Services acquired U.S. Well Services, one of the pioneers of electric frac fleets with more than 110 patents covering related technology. “Before the acquisition, we secured licenses through U.S. Well Services so we could build our own electric fleets,” he mentions. “The combined company has eight electric fleets, and we expect to have 12 early in 2023 as more roll off the line.”

Through vertical integration, including manufacturing pressure pumping fleets internally, ProFrac Services is navigating tough supply chains. The company says most future fleets will run partly or entirely on natural gas to reduce fuel costs and emissions.

The company’s horsepower also will include at least 13 Tier IV dual-fuel fleets by the first quarter of 2023, Wilks indicates. He says ProFrac builds both its electric and dual-fuel fleets internally to control costs and manage its supply chains. “Vertical integration helps us build electric fleets at a lower cost. The capital expense for the fleet itself is lower than it would be for a conventional diesel fleet,” he says.

“If we combined the costs for the fleet with the turbine that provides the electricity, the cost would be slightly higher,” Wilks allows. “However, we treat the fleets and turbines as separate businesses. The fleets compete with other pressure pumping equipment, while the turbines compete with diesel-based engines and are available on a rental basis through longer-term contracts.”

Given the fuel cost savings provided by natural gas turbines, Wilks deems the investment worthwhile. He mentions that displacing diesel has the side effect of improving air quality. “We are handling the E in ESG largely by following a maxim that is intrinsic to capitalism: Don’t waste what you don’t need,” he says. “In other words, we try to work as efficiently as possible.”

Enabling Efficiency

Fleets are becoming more efficient by reducing how long engines spend idling, Wilks says. He expresses pride in EKU Power Drives, a PF Holdings subsidiary that has developed a system to automatically shut down engines if they idle too long. EKU estimates that the system reduces engine idle time 80%, halving diesel deliveries and shrinking emissions.

The idle management system uses electric starters rather than hydraulic start and wet kits typical on frac sites, a change Wilks says greatly reduces the site footprint. “To accommodate hydraulic kits, a fleet with 50,000 horsepower would usually need 34-36 Class 8 tractors, or one for every pump. With the idle management system’s electric starters, we can reduce the trucks associated with each fleet to 10-12,” he details.

In cold temperatures, the idle management system periodically brings engines on line to keep fluids and catalysts warm so the equipment can turn on when needed, Wilks notes.

ProFrac has adopted big-bore frac manifolds, Wilks continues. “These manifolds allow us to equalize pressure from each pump,” Wilks says. “On a conventional manifold, we would have to equalize the line pressure across quadrants to prevent aggressive vibrations that could cause equipment failures.

“The big bore manifold allows more flexibility,” he contrasts. “Instead of treating the whole system as a single unit and balancing pressures as the number one priority, we can look at individual drive trains and optimize other factors, such as fuel consumption and equipment wear and tear. This extends engine, transmission and power end life, improves natural gas substitution rates on dual-fuel fleets and simplifies maintenance schedules.”

Ensuring Supply

Wilks stresses that even the best equipment needs to be supported by robust supply chains. “At PF Holdings, we focus on making sure we control the entire supply chain to protect ourselves from common procurement issues that can reduce our utilization rate or our ability to provide customers reliable service at an attractive price,” he says.

As part of that effort, the company is expanding its network of frac sand mines, Wilks relates. In December, PF Holdings acquired the Eagle Ford mining operations of Monarch Silica LLC, and a subsidiary signed a definitive agreement to acquire Performance Proppants, the Haynesville Shale’s largest in-basin proppant provider.

Wilks says ProFrac tries to anticipate potential supply chain problems before they affect service. “If anything gives us pause or concern, we will dig deeper and build the appropriate inventories,” he relates. “We want to keep everything as tight and lean as possible, and we track our cycle times very closely. However, we will invest in inventory to keep any tightness from impacting our operations. No one is happy when $40 million worth of equipment has to shut down because we are waiting on a $10 part.”

Wilks mentions that ProFrac has prepared for shortages by building inventories of packing and polymers. He adds that in 2021, the company’s manufacturing division moved its forgings from Europe to the United States. “We did not anticipate that Europe would shut down much of its manufacturing to conserve fuel for the winter, but we saw inflationary pressures and wanted to shorten lead times,” he says. “After moving forgings stateside, we have shorter lead times than ever.”

Direct Drive Turbines

As hydraulic fracturing equipment has become reliable enough for pumps to run 18-20 hours a day, reducing fuel costs has become more appealing, observes Seth Moore, executive vice president and chief operating officer of Catalyst Energy Services. “Today, fuel accounts for a third of a fleet’s operating cost,” he says. “Even small fuel savings have a huge impact across a month.”

To deliver a step-change in operating expenses, Moore says Catalyst developed a fleet that runs entirely on natural gas. “We looked at fielding a traditional electric fleet with a single turbine powering several pumps, but the capital cost was too high to fit our philosophy on spending,” he relates. “Instead, we decided to take the direct-drive approach, with much smaller turbines powering individual pumps.”

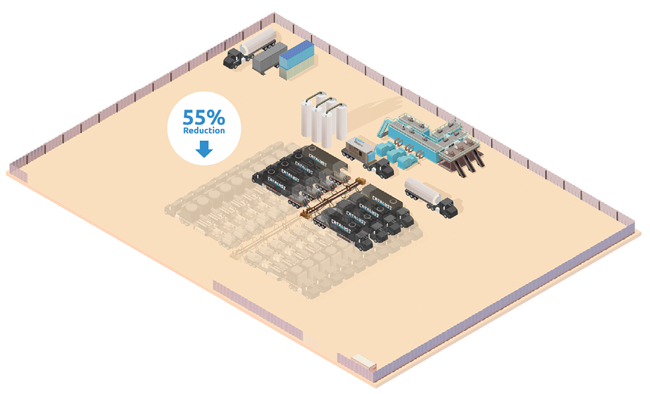

The trailers in Catalyst Energy Services’ newest hydraulic fracturing fleet carry 5,000-horsepower pumps powered by direct-drive turbines that run entirely on natural gas. This approach shrinks fuel costs and emissions, as well on-site footprints and truck traffic through local communities.

Each trailer has a single pump that delivers up to 5,000 horsepower and the associated turbine, Moore describes. “We pack a lot of horsepower into a small package,” he remarks. “The trailers are 48 feet from bumper to bumper, a noticeable improvement from conventional fleets’ 68-74 foot trailers.”

Such horsepower density means Catalyst needs fewer pumps on site, Moore says. “In the Permian Basin, our direct-drive fleet is running eight pumps to do jobs that normally take 20,” he illustrates.

The footprint for the direct-drive fleet can be as much as 55% smaller than the footprint associated with a conventional diesel or dual-fuel fleet, Moore calculates. “The reduced footprint is big,” he comments. “It saves customers money and minimizes environmental disruptions. We also have fewer trucks driving down the road, so local communities benefit as well.”

The trailers have been designed to be reliable and easy to maintain, Moore assures. “Not counting fuel, they should reduce operating costs 10%-15% versus standard fleets,” he estimates.

Emissions

When something unexpected occurs, crews can shut off the turbines to save fuel and mitigate emissions, Moore says. “The turbines take less than five minutes to bring back on line,” he explains. “This is much faster than a traditional diesel fleet with 20 pumps, which takes 40 minutes to turn back on even when the equipment is new. Most fleets take at least an hour to shut down completely.”

That long window encourages crews running traditional fleets to keep engines running as troubleshooting occurs, Moore suggests. Idling consumes fuel and increases safety risks, but it eliminates the chance of unnecessary nonproductive time if the problem gets resolved quickly, he explains.

Unfortunately, the time troubleshooting will require can be hard to predict. “When crew members spot a leak or other issue, they often think, ‘All we need to do is replace the gasket, so we will be back up in 10 minutes.’ Sometimes the initial fix works, but when it doesn’t, 10 minutes often turns into two or three hours,” Moore relates. “If the engines have been idling the entire time, the wasted fuel adds up. The faster starts with our new turbine technology help teams keep safety front and center while minimizing nonproductive time.”

The turbines’ flexibility and the advantages of natural gas limit emissions, Moore says. “We are working with a third-party group to quantify the emission savings from burning natural gas rather than diesel and shutting down more frequently,” he mentions. “The results differ from the numbers in original equipment manufacturers’ spec sheets because those numbers are based on new equipment operating at sea level in mild temperatures and specific humidity levels, but what we have seen so far has been impressive.”

The independent testing’s findings mirror those of a dissertation at the University of West Virginia that compares several frac technologies and concludes that direct-drive turbines offer the lowest emissions, Moore indicates.

As of late November, Catalyst Energy Services had one of the new fleets in the field and another under construction, as well as two more traditional fleets. Moore says his company can manufacture direct-drive fleets at a cost comparable with traditional ones.

“We purchase each unit’s pump, engine, gearbox and drive train but build all the equipment these components go into, then tie the components together,” he details. “In-house manufacturing lets us keep patent-pending technology under lock and helps us manage costs.

“The global supply chain issues we have seen since the pandemic are beginning to relax or at least become more predictable,” Moore reports. “Now that we have more reliable lead times, we can grow at a steady pace that preserves our safety record and sustainable operations.”

Other Initiatives

Moore points out that many operators simplify logistics by using locally mined wet sand as proppant. “Wet sand’s particle size distribution varies more than graded sand, which means we have to deal with pebbles that can cause problems in mixing and pumping equipment,” Moore notes. “There are technologies to protect the equipment, but they are evolving constantly. We are tracking those developments and evaluating the best options.

“Another area we are working on is the frac iron,” he continues. “Because of the extreme pressures and the types of sand that go through, the surface equipment sees a lot of erosion, which contributes to failures and nonproductive time. We are looking at ways to simplify the system and reduce failure points.”

Corrosion often contributes to surface equipment failures, Moore says. “Many traditional biocides, such as chlorine dioxide, sodium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide, can be extremely detrimental to equipment. They also can accelerate erosion by interfering with the friction reducers that normally limit sand’s effects,” Moore cautions. “We plan to offer customers alternatives that are equally effective but have fewer negative side effects.”

Electric Wireline

When the first electric hydraulic fracturing fleets began to appear, Horizontal Wireline Services became extremely curious about their appeal. “We wondered why companies would invest in electric frac fleets when diesel was easy to get, familiar and far more affordable than it is today,” recalls Joseph Sites, Horizontal’s chief executive officer. “As we talked with our customers, many predicted the fleets would provide significant efficiency gains as well as environmental benefits.”

If frac fleets were using turbines to generate power for their pumps, Horizontal reasoned that electricity would be available for other equipment and began investigating electric wireline units’ potential. “Had we known all the benefits ahead of time, we would have moved to electric much sooner,” Sites says. “From an environmental standpoint, electric units make total sense. But once we started constructing these units and realized how much modern electronics and software could improve wireline operations, we knew they had huge safety and economic advantages as well.”

Controlling wireline units with electric motors rather than hydraulic systems enables faster and more precise adjustments. According to Horizontal Wireline Services, that precision lets many tasks be automated, allowing the units to pump down twice as fast while improving safety.

Because an electric motor is far more responsive than the hydraulics traditionally used on wireline units, it can leverage software to make decisions at a speed no human can match, Sites reports. For example, if the winch detects excess tension, it will stop automatically to prevent the wireline cable from breaking.

With enough testing, software also can automate routine tasks, Sites adds. “We are at a point now where we can automate pump down completely,” he says. “Site supervisors still monitor the job, but their roles have shifted. Instead of devoting 80% of their attention to controlling the winch, they only need to intervene if something unusual happens.”

The automated operations have freed supervisors to focus on other tasks, such as ensuring their teams are working safely, Sites says. “Our electric wireline units not only increase efficiency and consistency, but also improve safety and service quality,” he reports.

The efficiency gains are dramatic, he continues. “With a mechanical wireline unit, the pump down speed would average 400-500 feet a minute. With the electric system, we have gone 2,300 feet a minute during tests. That speed is unnecessary during day-to-day operations, but on most jobs, we can run up to 1,000 or 1,200 feet a minute. We are doubling the speed but operating so far below the unit’s maximum capability that we have incredible safety margins.”

Eliminating the high-pressure pumps and lines associated with hydraulics also improves safety, Sites notes. “Even without the safety benefits, employees tend to be happier in electric units,” he says. “When the wireline is moving, the sound inside is about the same as driving down the highway with the windows up and the air conditioning off. The units do not create any emissions, so the air is cleaner.”

Between the efficiency gains, safety advantages and emission reductions, Sites says electric units can outperform their diesel counterparts in any situation. “We used to wonder whether conventional units would be better when power isn’t available,” he acknowledges. “But as funny as it looks, it’s smarter in that situation to bring a diesel-powered generator on site to drive the electric unit, because that generator will create half the emissions as a large diesel motor.”

In late November, Sites said Horizontal had eight electric wireline units in the field, with three more scheduled to be built by the end of 2022. “Our supply chain has settled enough that we should be able to add a unit every month in 2023,” he commented.

Over time, Sites predicts that electric wireline units will become increasingly automated. “We are not looking to replace individuals at the well site, but we do want to put more safeguards and backups around them in case they make a mistake,” he outlines. “Eventually, we think we will be able to fully automate perforating by using independent systems to confirm the guns have reached the proper depth and can be fired safely.”

Fuel Valves

Even with proper conditioning, the turbines that now power many frac pumps must contend with variations in gas quality, observes Keith Flitner, senior business development manager at Continental Controls Corp. “Our smart fuel valves adjust the amount of fuel as the quality changes,” he says. “They are precise enough to help the turbine maintain the desired load and reduce downtime and maintenance costs.”

The smart valves minimize the risk of issues during startup, Flitner adds. “These issues have plagued turbines since the day they were invented,” he reflects. “Starting a turbine requires unloading the gas compressor while igniting fuel in the combustion chamber. By matching fuel with air flow, we can ensure the ignition goes smoothly.”

Smart fuel valves help turbines start and run smoothly, which saves fuel, minimizes emissions and simplifies maintenance. In addition to being installed in new turbines, including ones for hydraulic fracturing fleets, Continental Controls says the self-contained valves can be retrofitted on much older turbines used in other applications.

When the fuel mix is off kilter, technicians often hear booms coming from the back of the turbine as it tries to start, Flitner says. “With a properly-controlled smart valve, the biggest sign the turbine has started is numbers appearing on a screen,” he contrasts. “The difference is stark enough that people who try the valves often promote them.

“Once the turbine is running, the self-governing valve optimizes fuel flow to reduce fuel consumption, emissions and maintenance,” Flitner reports.

According to Flitner, Continental Controls’ smart valves offer precise control because they combine fast servo control with aerodynamic designs that minimize pressure drop across the valves. “The onboard computer and the nested control logic we have developed over the years also are key to the valves’ performance,” he adds. “The control logic excels at evaluating several factors to determine how the valves should respond.”

The valves have a tremendous turndown ratio, Flitner reports. “They can handle the low flows that occur as the turbine starts and the high flows it needs at full load,” he assures. “Across the full range, the valves have at least 0.5% accuracy. The control is more precise in certain areas, and we can customize those for specific applications.”

Enabling Retrofits

In the hydraulic fracturing market, most of Continental Controls’ smart valves are installed on new equipment, Flitner says. “However, the valves can be retrofitted onto turbines and reciprocating engines, even ones with analog control systems,” he says. “The computer and sensors are embedded in the valve itself, and it can run off a simple 4-20 milliamp control signal, so we can provide precise control without a complete system overhaul.”

Such overhauls can cost six digits, Flitner reports. “With our smart valve, the cost is in the low double digits,” he contrasts.

“Our lead times are short. We often deliver products in a month or less that would involve six-month lead times elsewhere,” Flitner adds. “We have seen the same supply chain issues as everyone else, but because we manufacture our own circuit boards and handle machining internally, we can recover from them more easily.”

Flitner predicts that retrofitting equipment will become increasingly important as the time, cost and risk associated with permitting new facilities grows. “We recently upgraded a plant for Kinder Morgan in Arizona that had units from the 1950s. The plant had been mothballed, but at today’s prices, it made sense to bring it back on line,” he relates.

The potential for upgrades applies to both turbines and reciprocating engines, Flitner maintains, noting that Continental Controls introduced a next-generation fuel valve for small-to-medium-sized engines at the Gas Machinery Research Council’s conference last October. This valve supports the flow ranges often required to run on field gas that otherwise would be flared.

Continental Controls is doing everything it can to simplify the work associated with retrofitting equipment, Flitner remarks. “Our average customer’s experience level is changing,” he observes. “Past recessions mean that many companies have two bulges, with many workers over 50 and many younger than 30. These companies are trying to ensure knowledge gets passed on, but that process never goes as well as we would like.”

With that reality in mind, Continental Controls is creating YouTube videos that explain how to install and commission its valves, as well as how to operate and troubleshoot them. “Many customers, even ones with limited training, want to try solving a problem themselves before they call us. They frequently turn to Google for answers, and we want to make sure they can find them,” he explains.

Flitner emphasizes that these videos must be backed by accessible support. “We still put our phone number and website on every part we ship, and we do not send callers through an automated maze before they talk to a human,” he assures. “We also have introduced a WhatsApp number, which allows international customers to reach us using the Internet rather than a cell phone or text.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.