Permian Basin Groups Prepare For Long Future By Investing In Infrastructure

By Colter Cookson

May estimates by the U.S. Energy Information Administration show that the average Permian Basin drilling rig contributes 1,386 barrels of oil and 2,536 Mcf a day to U.S. supplies. That is a testament to advances in drilling efficiencies, completion designs and artificial lift systems.

It’s also a reflection of the Permian Basin’s people, who are renowned as hardworking problem-solvers. But the resource beneath their feet is so vast that even they only can hope to unlock its full potential by convincing talented people from elsewhere to make their homes in the Permian Basin.

“One economic study estimated that by 2040, the Permian Basin would need to bring in 190,000 workers to maintain production,” says Tracee Bentley, president and chief executive officer of the Permian Strategic Partnership. “As the population expands, we need to make sure the basin continues to be a place where people want to live. Studies suggest that will require transformative progress in four areas: healthcare, education, workforce development and road safety.”

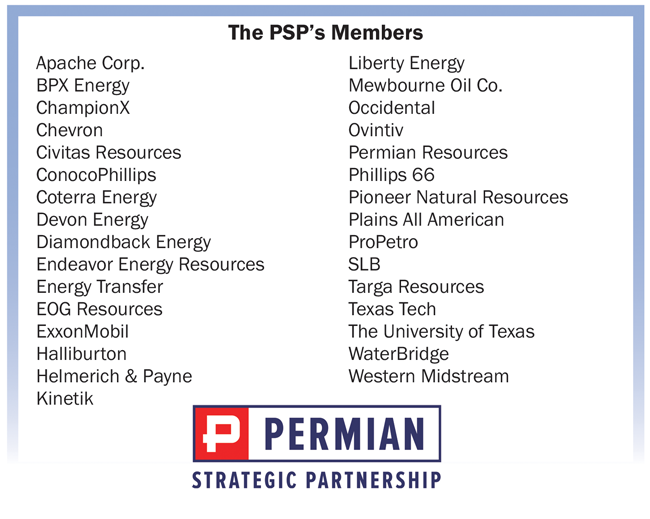

Many of these studies come from the PSP itself, which formed in 2019 when several oil and gas executives began discussing the workers they would need in the short term and in the decades to come. As of early June, the group consists of 31 producers, service companies and universities (Table 1).

“We use a unique model focused on public-private partnerships,” Bentley describes. “We take contributions from our members and partner with federal and state organizations, philanthropic groups and local communities to get the transformative effect the Permian needs.”

That approach works well, Bentley assures. “We have spent $160 million in our communities, but we have leveraged that $160 million into more than $1.5 billion in collaborative investments,” she reports.

“Partners are more excited and willing to be part of a huge project when communities have skin in the game,” she says. “When we ask for federal or state dollars and can say, ‘Here are the investments we are already making, and here is what we are willing to do with support,’ they can see how important the issue is. They also know their contributions will go further when they are not doing the entire lift alone.”

Road Safety

One of the most immediate concerns is road safety. “Our studies show that the Permian Basin has some of the most dangerous roads in the country. At times, we even average a fatality a day,” Bentley says. “We are working with the departments of transportation in Texas and New Mexico to prioritize Permian roads. To date, we have helped bring in $800 million to upgrade outdated roads that were never designed for the traffic they see today.”

Driver training also is vital, Bentley says. “Many local truck drivers do not have a commercial driver’s license,” she notes. “We have partnered with Odessa Community College to expand its truck driving academy so companies can employ more certified drivers, which should make roads much safer.”

In the Permian’s rural areas, responding to accidents often falls to volunteers with limited funds, Bentley adds. She says the PSP is helping equip these first responders with jaws of life and the other life-saving tools.

As the region’s population expands, the PSP predicts the need for doctors will grow. “Early on, we partnered with Texas Tech University, which has one of the country’s strongest rural family health programs, to expand doctor residency programs, behavioral health fellowships and surgery residencies,” Bentley relates. “By allowing people from the Permian Basin to study locally, we hope to increase retainment.”

Early indicators suggest that strategy is working, Bentley shares. “We are starting to see people from the doctor residency programs look at opening their own practices or joining one of the hospitals here in the Permian,” she illustrates.

To support mental health, the PSP has worked with private donors and the Texas legislature to fund the first regional behavioral health center, Bentley continues. When it is complete, the center will have 200 beds capable of serving patients from Texas and New Mexico.

“We have also partnered with the University of Texas Permian Basin to expand its nursing program and licensed behavioral health programs,” Bentley adds. “We hope to mitigate the nursing shortage and see more counselors and practitioners out of their program that will be ideal candidates for the new behavioral health center.”

Workforce Development

The Permian Basin also needs more HVAC technicians, plumbers and electricians, Bentley mentions. She says the PSP has helped an Austin-based group called Skillpoint Alliance bring its training programs to the Permian Basin.

Those programs have had life-altering effects in East Texas, Bentley says. She explains that they remove many of the barriers to pursuing a trade by training people quickly, paying them during training, and guaranteeing graduates a job.

To assist younger students who want to enter the workforce during or immediately after high school, the PSP has helped build the Career and Technical Education Center in Hobbs, N.M., which prepares students for careers in the energy, manufacturing, transportation, culinary and hospitality, information technology, and construction and architecture sectors. Bentley says the school has been a huge success and notes the PSP is supporting a similar effort in Odessa.

“The Permian Basin has an opportunity to become one of the country’s most veteran-friendly regions,” she adds. “The skills we need match veterans’ capabilities. They have strong technical skills, they know how to work in and lead teams, and they can make decisions under pressure.”

To help veterans capitalize on the Permian’s many opportunities, the PSP has allied with America’s Warrior Partnership to provide what Bentley calls a comprehensive program. “When a veteran and his or her family get here, a job is only part of the experience,” she reflects. “We want to make sure veterans are aware of employment opportunities for their spouses, the schools and health care services they have access to, and social opportunities so they feel like a part of the community.”

Education’s Importance

Bentley stresses that a robust education system is the foundation for attracting permanent residents. “It is hard to recruit and retain doctors, nurses, counselors, teachers or technicians of any type if they cannot put their kids in good schools,” she says. “Today, about 60% of the Permian’s students are not going to A- or B-rated schools, well below the average in Texas and New Mexico. That is not acceptable for families here.”

The Texas Department of Transportation has broken ground on a project to upgrade the intersection between State Highway 191 and Farm-to-Market Road 1788. According to the Permian Strategic Partnership, this project will improve safety and ease access to health and education facilities, including the Permian Basin Behavioral Health Center, a regional mental health facility that will provide both in-patient and out-patient services when it opens in 2026.

To expand access to high-quality education, the PSP is helping well-regarded public charter schools come into the Permian and supporting existing public schools, Bentley outlines. She says many of the organization’s investments focus on building leadership skills.

“Strong principals retain strong teachers, and strong teachers improve student performance,” she explains. “We want a deep bench of potential leaders so that when a principal retires, schools have several people who can take over and do well.”

Toward that end, the PSP has asked the Holdsworth Center in Austin, Tx., to provide principal training in the Permian Basin, an effort that Bentley says has proven extremely successful. “We are also providing funding for principal internships where a principal in training can work with one of the best principals to get hands-on experience beforehand so they will be ready to take over their own school,” she adds. “For teachers, we are paying for the necessary training to become National Board certified, the gold standard for teaching certification.”

In partnership with the Cal Ripken Foundation, the PSP has installed science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) centers in every third grade classroom, Bentley mentions. “In third grade, performance in math and science often drops in underserved regions where STEM education is less prevalent or only begins in middle school or high school,” she reports. “We want to expose students to STEM much earlier so they know they can do it and start asking questions about the world. The centers let us do that in a fun and practical way.”

Bentley attributes the PSP’s wide-ranging impact in its first five years partly to the quality of its leadership. The organization is chaired by Donald L. Evans, a longtime oilman who served as Secretary of Commerce during President George W. Bush’s tenure. The board of directors, which sets the group’s direction and has the final say on the projects it funds, consists of each member’s CEO.

“With the very top leader of each company involved, things tend to get done on time and in a big way,” Bentley says. “The buy-in from leadership shows how much the members want to improve their communities.”

Proppant Delivery

About half the oil field traffic in West Texas relates to sand deliveries, estimates Kyle Turlington, vice president of investor relations for Atlas Energy Solutions. “If we can reduce that traffic, we can make communities safer, reduce emissions and increase the Permian Basin’s efficiency by enabling drivers to do shorter hauls,” he predicts.

The importance of advancing proppant logistics is rising as completion efficiencies improve and en route sand volumes increase, Turlington suggests. “The average hydraulic fracturing crew has gone from pumping sand 16 or 17 hours a day a few years ago to pumping well north of 20 hours a day,” he compares. “Combine that with longer laterals and the growing popularity of simulfracs, and the amount of sand an average crew pumps each month has jumped from 40,000 to 65,000 tons.”

To simplify sand delivery, Turlington points out that Atlas is building the Dune Express, a 42-mile conveyor belt that extends from Atlas’ mine in Kermit, Tx., to the middle of the Delaware Basin. “The conveyor is powerful,” he says. “We expect it to shorten average hauls in the Delaware from 70 miles to 15 or 20.”

Although using conveyor belts to transport proppant may be new, Turlington says conveyors have a long history of hauling bulk materials for other types of mines, including many in the United States and Canada.

The Dune Express is scheduled to enter service in the fourth quarter. It has two permanent load-out facilities, which are helpfully named End of Line and State Line, but Turlington says Atlas can deploy mobile equipment to retrieve sand at any point along the belt.

“Because of the uniqueness of the Delaware, almost none of the trucks that carry the sand will touch public roads,” Turlington adds. “Instead, they will be on private lease roads, which can reduce traffic on public roads as much as 70%.

“To accommodate weight restrictions on public roads, a typical sand truck carries 24 tons,” he notes. “We designed our trailers to hold 35 tons when they are on private roads, and we can have each truck haul two or three trailers for a total capacity of 105 tons. Compare one driver carrying 105 tons doing a 15 mile drop off versus one driver carrying 24 tons doing a 70 mile drop off, and it is easy to see how much more efficient our last mile will be once the Dune Express is here.”

Mobile Mines

To reduce miles driven in areas far from the Winkler sand trend or the Dune Express, Atlas employs mobile mines that can extract sand from small deposits close to activity, Turlington mentions. He notes that the company acquired these mobile mines when it purchased Hi-Crush Inc. in March.

The company estimates that the mines cut driving distances as much as 90% in some instances. “The mines tend to be 20 or 25 miles from the well site,” Turlington explains. “Many of them are in Howard County, Tx., which is far enough from the Winkler sand trend that sand delivery rates can be two or three times as high as they are for the Delaware or for other parts of the Midland Basin.”

The mines target small deposits containing three-five years of reserves, Turlington describes. “An average mobile mine produces around 700,000 tons annually,” he says. “For context, our Kermit facility produces 10 million tons annually, and our Monahans facility produces 5 million.”

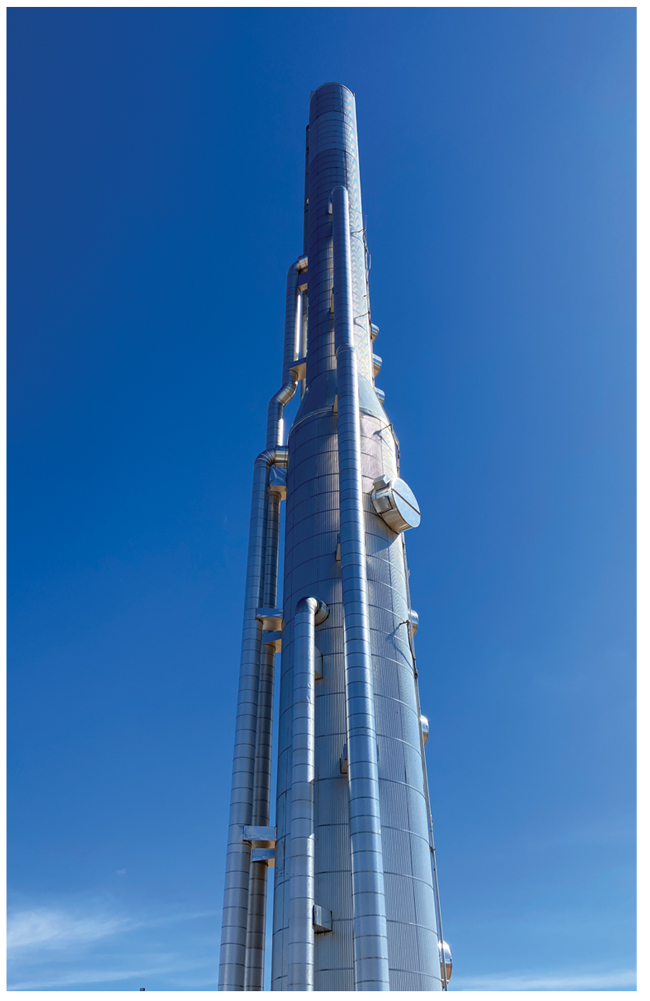

To improve road safety and streamline proppant deliveries, Atlas Energy Solutions is building the Dune Express, a 42-mile conveyor belt from its sand mine in Kermit, Tx., to the heart of the Delaware Basin. The company says the belt will ease truck traffic by reducing the miles driven for a typical Delaware Basin delivery from 70 to 20.

The mobile mines are too small to justify drying equipment, so they produce wet sand. In areas close to a traditional mine, Turlington says operators mainly prefer dry sand. But in remote areas, the logistical cost savings associated with a nearby proppant supply easily can justify any downsides from wet sand.

“The Permian has become a factory on the ground,” he reflects. “We are trying to make that factory as efficient as possible.”

With that goal in mind, Atlas is using machine learning tools to automate orders. “When the sand levels on a site fall below a certain point, the system will automatically order more sand. To fill the order, we can use an automated dispatch system that is similar to Uber. Instead of issuing a general call for a driver, it starts by signaling the driver who will be able to pick up and deliver the sand quickly.”

Dredge Mining

To minimize mining costs, Turlington says Atlas tries to target the best reserves. “At both Monahans and Kermit, we have extremely high yields over 90%, meaning that for every ton of sand we run through our plant, 90% comes out as product,” he says. “That is really important for keeping costs low.”

Automation and dredge mining also play a role. “Dredge mining allows us to reduce the amount of equipment and maximize use of personnel on site,” Turlington says. “We have access to water on our sites, which allows Atlas to be the only sand company in the Permian that utilizes dredges to feed our plants.”

The company plans to investigate whether the water at one of the mines it has acquired from Hi-Crush can support dredge mining by moving a rental dredge there this summer, Turlington mentions. “If we discover that the mine’s water does not work, our Kermit facility is only 1.8 miles away, so we could possibly use our existing pond to feed Hi-Crush’s plants using our more robust new dredges.”

To improve dredge mining economics, Turlington says Atlas has commissioned two new electric dredges designed for sand mining. He describes these dredges as larger and more reliable than their predecessors.

“We will be able to mine almost three times as much sand a day with them,” Turlington envisions. “This should let us go from feeding 50%-60% of the sand our plant processes with a dredge to almost 100% dredge feed, which will eliminate the higher costs associated with relying on yellow iron to mine. We will still need some yellow iron because even purpose-built dredges have some downtime, but the cost savings will be significant.”

Tanks and Vessels

As consolidation and skilled landmen enable operators to drill longer laterals and access more rock from each pad, the industry may need fewer tank batteries to handle production, suggests Michael Duffy, CEO and president of Petrosmith Equipment LP. However, he predicts, those tank batteries will likely be larger.

By upgrading its factory in Abilene, Tx., Petrosmith Equipment LP reports it has gained the ability to manufacture the particularly large vessels that many sites in the Permian Basin require. These vessels include hatchless production and storage tanks that reduce emissions and increase revenue by keeping more hydrocarbons in solution.

Other equipment is getting bigger as well, Duffy reports. “We see demand for larger and larger equipment as activity in the Permian has trended westward and farther into the Delaware Basin, where wells often have higher water cuts,” he says. “Handling that water will require bigger vessels and pipes.”

With these trends in mind, Petrosmith has upgraded its main campus in Abilene, Tx., to produce some of the largest and heaviest vessels associated with upstream equipment, Duffy relates. “Our large vessel shop gives us the ability to manufacture a new product, a hatchless production and storage vessel that reduces emissions relative to standard API 12F tanks while having the ability to enhance oil recovery,” he mentions.

Because the new production and storage vessel has no thief hatch and supports higher operating pressures, hydrocarbons that normally would vaporize instead stay dissolved in solution and can make it to the sales line, Duffy reports. “It eliminates the need for a vapor recovery tower and allows the vapor recovery unit to have a wider operating range and lower horsepower requirements,” he says. “The hatchless vessel slightly increases the facility’s upfront CapEx cost, but it pays for itself quickly by enhancing oil recovery.”

Modular Facilities

To achieve more with every dollar they invest, Duffy says many operators are turning to Petrosmith’s modular construction services, which shorten field work by building as much as possible on skids in the factory. These skids are pre-fitted at the company’s production facility, shipped to site and assembled in a fraction of the customary time, he reports.

“The time savings vary based on how big a facility is, but we have done 12-well facilities in 10 days that customers told us would normally take 60-75 days of field work,” he contrasts.

That speed comes from planning and coordination, Duffy notes. “When an operator wants a fully modular approach, the skids house all the oil, water and gas lines to take fluids from the well through the vessel train to the tanks and out to the LACT and the flare. This includes all the interconnecting pipes that link skid to skid,” he notes. “Before shipping any skids to the field, we do test fits on each one to ensure a proper alignment and fit, which drives field efficiency.”

“The delivery and installation are coordinated,” he adds. “Trucks arrive in a defined sequence and crane moves are planned so equipment can be offloaded, connected and set up quickly.”

Such planning requires upfront engineering. For a full production facility, Duffy generally recommends allowing 12-14 weeks for engineers to discuss operators’ needs, design and optimize the skids, and verify that they meet expectations. He says this methodical design process improves facility quality and helps shrink overall material costs.

“When nearly everything needs to go on a skid, the designers have to think about how to bring fluid into the skid and move that fluid where it needs to go as efficiently as possible,” he says. “Compared to stick-built designs, modular facilities generally have less piping and fewer elbows, Ts and bends. They reduce overall facility costs not only by eliminating costly field days, but also through more efficient pipe routing and lower material costs.”

Since most of the work is done in a controlled environment, Duffy says modular construction can keep costs predictable. “Putting some of the more challenging work in a shop, where we have overhead cranes and capital equipment to help with fabrication and construction, can improve worker safety and minimize potential incidents in the field,” he adds.

Given how much upfront engineering it requires, the modular approach can be a poor fit for small facilities with one or two wells, Duffy acknowledges. “However, for large facilities, especially ones that will need to expand in the future, modular designs really help,” he says. “If a pad is starting with eight wells but will eventually go to 16 or 24, we can put expansion slots in so that all the operator needs to do to bring new wells on is tie in a new separator and sometimes a new heater.”

Modular designs also make it easier to move equipment to new wells as production declines, Duffy notes. “That is a welcome advantage for operators who are focused on capital discipline,” he concludes.

Gas Processing

The demand for gas processing equipment will likely grow in the future, assesses Kevin Blount, CEO of BCCK. “We have a longer backlog and more high-probability prospects in the gas processing space, and specifically the nitrogen rejection area, than we have had for a long while,” he reports.

Blount attributes the steady activity partly to international conflicts, which have supported oil prices and therefore associated gas production by reinforcing many countries’ desire for energy independence or at least supply diversity. The environmentally-motivated quest for a reliable but relatively clean power source also plays a part, he suggests.

Liquefied natural gas export terminals’ need for gas with relatively low nitrogen concentrations is helping spur construction of nitrogen rejection units, BCCK relates. This NRU features a new technology to minimize the methane content in its vent gas.

Meeting global demand will mean more liquefied natural gas exports, which Blount says is one of many forces driving construction of nitrogen rejection units at gas plants and export facilities. “Nitrogen lowers the heating value of LNG, creates storage issues (called rollover) and complicates the liquefaction process,” Blount explains. “As a result, LNG export terminals want gas that has a nitrogen concentration of 1% or less.”

This is much lower than the 3% concentration typically allowed by U.S. pipelines, Blount says. “Historically, the United States has had such an abundance of natural gas with low nitrogen concentrations that many gas plants could meet pipeline specifications by blending low-nitrogen gas with high-nitrogen gas,” he recalls. “Today, blending is much less of an option because so much gas comes from the Midland Basin and other areas with high nitrogen concentrations.”

As the need for nitrogen rejection units grows, BCCK will continue looking for ways to shrink their capital and operating costs, Blount assures. “For example, we try to reduce construction in the field. Our designs involve more factory-built skids than traditional designs, which means they require fewer construction hours to build.

“Our latest two-tower NRU design needs 15% less horsepower and therefore has lower capital and operating costs for compression,” he continues. “Like its predecessors, the design has a small footprint and no moving parts, which simplifies maintenance.”

Regulations and public perceptions have made it increasingly important to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, Blount observes. “The amount of methane that comes from an NRU’s overhead vent is small, but even relatively small quantities can lead to costly fines,” he says. “Anticipating that, we have developed a technology that reduces the methane content in the vent gas to as low as 10 parts per million. We can design this technology into new NRUs and retrofit it to existing plants.”

Other Technologies

The concept behind the ultralow-methane NRUs may apply to gas processing’s other components, Blount envisions. “We are actively investigating that possibility, because we know emissions will continue to be a concern for plant operators,” he says.

BCCK also is trying to help plants adjust to commodity price shifts, Blount reports. “We have invented a natural gas liquid extraction process that allows plants to operate efficiently in both ethane rejection or ethane recovery,” he illustrates. “It is a nice improvement over older technologies, which favor either rejection or recovery.”

In ethane recovery mode, this process extracts 98% of ethane and almost all the heavier components. In ethane rejection mode, it reduces ethane recoveries below 2% but still captures at least 98% of the propane, Blount details.

Another technology can be retrofitted to gas-subcooled process plants to improve propane recovery, Blount relates. “The GSP process is rarely used in new plants today, but there are about 200 in the United States. By design, they operate poorly in ethane rejection with respect to propane recovery,” he says. “Our unit solves that problem. It can improve propane recovery in ethane rejection by three or four points, delivering a meaningful increase in revenue.”

The retrofit can take place during a maintenance shutdown, Blount says. While he acknowledges that the technology is a poor fit for some GSP plants, he says the relatively fast installation and extra income generally offer compelling economics. “For one 200 Mcf/d plant, we calculated that payback would occur sooner than two years,” he demonstrates.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.