U.S. Moving Forward On LNG Exports

By Greg Matlock

HOUSTON–Global demand for liquefied natural gas has risen an estimated 7.6 percent a year since 2000, nearly three times faster than the estimated 2.7 percent a year global natural gas demand has grown over the same period, according to various reports.

More than half of global LNG demand in 2012 can be attributed to three Asian countries–Japan, South Korea and Taiwan–which have been and are expected to remain at the core of the global LNG market.

Between 2013 and 2020, Moody’s Investors Service estimates Japan will remain the largest importer of LNG, accounting for roughly a third of the global LNG market (with South Korea holding steady as the second largest importer). China, India, the Middle East, Europe and South America are emerging as significant LNG demand markets as well. However, these latter demand centers tend to have more competitive energy options, including coal, oil and other sources of natural gas, and generally will be more price sensitive and less likely to willingly pay supply security premiums than the premium markets.

Adding fuel to the fire, LNG demand is expected to grow 5-6 percent a year through 2020 (and is anticipated to continue growing after 2020 at a slightly lower rate). More than 30 countries have proposed plans to build or add LNG import/regasification capacity. By 2020, the number of countries with import capacity is projected to double from the 25 that had import capacity at the end of 2011.

Export Approvals

As a natural response to this steady increase in demand, U.S. companies, which have access to relatively economically preferable natural gas, are clamoring to assume a role in providing LNG exports to these premium markets. However, U.S. law requires, in part, an export license from the Department of Energy in order to export LNG.

Exporting LNG to a nation that has a free trade agreement with the United States generally is considered to be in the public interest and typically is approved without modification or delay. But when it comes to exporting LNG to non-FTA countries, the DOE has greater latitude in modifying the terms and/or stipulating conditions when considering applications.

According to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the United States has FTAs with 20 countries, five of which already import LNG (Canada, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Chile and South Korea). A sixth country, Singapore, is expected to have import capacity by the end of this year.

A proposed new FTA, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), is under negotiation among Australia, Brunei, Chile, Canada, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, Peru, New Zealand, Vietnam and the United States. If approved, it would be a game changer for global LNG demand since U.S. LNG exports to new TPP partners would be presumed to be in the U.S. “public interest.”

In addition to the aforementioned countries, the Obama administration notified Congress on April 24 of its intent to include Japan–the world’s largest LNG importer–in the TPP agreement negotiations. Furthermore, a number of proposals to expand and expedite U.S. LNG exports have been raised in the 113th Congress.

As of Sept. 19, DOE listed 32 applications to export domestically produced LNG, with 25 of those applications seeking authorization to export LNG to non-FTA countries. After a significant halt in conditional approvals, between May and September this year, DOE announced three additional conditional approvals for exporting domestically produced LNG to non-FTA countries, bringing the total to four such approvals.

History

The first DOE approval was granted to Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass Liquefaction LLC more than two years ago. After approving Cheniere’s Sabine Pass export application, the DOE had delayed issuing additional non-FTA authorizations, pending a two-part economic study commissioned by its Office of Fossil Energy to determine how LNG exports might affect U.S. supply and global markets.

The two-part study was performed by the Energy Information Administration and a private contractor, NERA Economic Consulting. Part one of the study was released in January 2012 and considered 16 scenarios under different assumptions on gas supply, demand and exports. The EIA study identified as the four primary impacts of increased natural gas exports:

- Higher domestic natural gas prices;

- Increased domestic natural gas production;

- Reduced domestic natural gas consumption; and

- Increased natural gas imports from Canada.

In December 2012, NERA issued a report in connection with the second part of the study on the potential macroeconomic impact of U.S. LNG exports on the U.S. economy under a variety of assumptions regarding levels of exports, global market conditions, and the cost of producing natural gas in the United States. After analyzing several scenarios for global supply and demand, NERA concluded that under any of the scenarios, U.S. LNG exports would not harm the U.S. economy, but, instead, the overall impact would be a net positive.

Positive Impacts

One of the key findings in NERA’s report is that to the extent the U.S. exports LNG, domestic natural gas prices typically will increase. However, the global market limits the amount of such an increase since importers will not purchase U.S. exports if U.S. wellhead prices rise above the cost of competing supplies.

The report finds that the macroeconomic impacts of LNG exports are positive in all cases. Under each of the scenarios considered by NERA, the United States is projected to gain net economic benefits from allowing LNG exports. Additionally, for each scenario examined, the net economic benefits increase as the level of LNG exports increase. Furthermore, across the scenarios (including unlimited exports), U.S. economic welfare consistently increases as the volume of natural gas exports increases.

Sources of income will shift. Although the report shows that LNG exports result in higher total U.S. income, the expansion of LNG exports may raise energy costs and, as a result, depress both real wages and the return on capital in all other industries. However, allowing LNG exports to non-FTA countries also could create two additional sources of income:

- Higher export revenues and wealth transfers from incremental LNG exports at higher prices paid by overseas purchasers; and

- Natural gas resource income or rents.

The study shows that the benefits derived from export expansion outweigh the losses from reduced capital and wage income to U.S. consumers. Hence, LNG exports were found to have net economic benefits in spite of higher natural gas prices.

NERA recognizes that some groups and industries will experience negative effects from LNG exports. Although different socioeconomic groups depend on different sources of income, an increasingly large number of workers are able to share in the benefits of higher income to natural resource companies through retirement savings and investment. Nevertheless, impacts will not be positive for all groups in the economy.

Households with income solely from wages or government transfers, in particular, may not participate in these benefits. Higher natural gas prices resulting from LNG exports may have negative effects on output and employment in sectors that make intensive use or consumption of natural gas, while other sectors (e.g., natural gas production, transportation and liquefaction facilities construction) could benefit.

Overall, NERA concludes, declines in output in other sectors are accompanied by similar reductions in wages in such sectors, indicating that some shifting of labor between different industries may result. However, the study says that employment reductions won’t be more rapid than normal turnover in any of the sectors it analyzed. In fact, the study hypothesizes that most of the changes in real worker compensation likely will be in the form of lower-than-expected real wage growth because of the increase in natural gas prices relative to nominal wage growth.

Highest Net Benefits

Peak natural gas export levels and resulting price increases are not likely. According to NERA’s study, net benefits to the United States will be highest if:

- The United States becomes able to produce large quantities of shale gas at low cost.

- World demand for natural gas increases rapidly.

- LNG supplies from other regions are limited.

If any of these factors are substantially absent, the United States will not likely export LNG, and under such conditions, allowing exports of LNG likely will cause no change in natural gas prices and do no harm to the overall economy. Natural gas price fluctuations attributable to LNG exports remain in a narrow spread across the entire range of scenarios.

Since the costs of liquefaction, transportation and regasification are expected to keep U.S. prices well below those in importing regions, under none of the scenarios analyzed in the study do U.S. wellhead prices rise to Btu parity with oil prices, even if the United States allows exports to regions where natural gas prices are linked to oil.

The NERA study finds that serious competitive impacts of exporting LNG are likely to be confined to narrow segments of industry. Approximately 10 percent of U.S. manufacturers have both material exposure to foreign competition and energy expenditures greater than 5 percent of the value of their output. Such energy-intensive, trade-exposed industries, which for the most part process raw natural resources into bulk commodities, account for 0.5 percent of total U.S. employment.

NERA’s study finds that under no scenario are energy-intensive industries as a whole projected to experience a loss in employment or output greater than 1 percent in any year, which is less than normal rates of turnover of employees in the relevant industries.

Even with unlimited exports, the study concludes there would be net economic benefits to the United States.

NERA also estimates economic impacts associated with unlimited exports. Under such a scenario, U.S. natural gas prices do not rise to oil parity or to levels observed in consuming regions, and net economic benefits to the United States increase, compared with corresponding cases with limited exports. Significantly, the study finds that scenarios with unlimited exports always have higher net economic benefits than corresponding cases with limited exports.

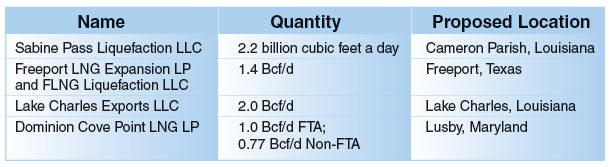

After a significant time lapse following its conditional approval of Cheniere’s Sabine Pass liquefaction project, DOE has conditionally approved LNG export applications from Freeport LNG Expansion LP and FLNG Liquefaction LLC (May 2013), Lake Charles Exports LLC (August 2013), and Dominion Cove Point LNG LP (September 2013). Table 1 shows LNG export approvals as of Sept. 19.

Global Expectations

Even with reasonably strong demand growth, the amount of LNG capacity proposed globally implies growing supply-side competition (on a global scale) and upward pressures on development costs and downward pressures on natural gas prices. Nevertheless, the very positive longer-term outlook for natural gas is driving investment decisions, both in terms of buyers’ willingness to sign long-term contracts and sellers’ willingness to commit capital to develop the needed projects.

Supply/demand magnitudes and dynamics aside, the biggest potential impacts are on LNG pricing:

- Will oil price linkages continue to dominate global LNG contract pricing?

- Will there be room for spot gas price linkages?

- Will divergent regional gas prices show signs of convergence?

Prior to the three conditional export application approvals DOE granted this year, the industry and markets were left in suspense, eagerly waiting to learn how the two-part study would impact the stagnant queue of LNG export applicants. Even after the reports were released and the conditional approvals were granted, anyone expecting to hear of bright lines being drawn, or even a more transparent approval process, likely will be disappointed.

DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy has provided that LNG export applications will be considered only on a case-by-case basis in light of the economic conclusions of the study, and that it will evaluate the cumulative impact of each authorization to determine whether authorizing it could pose a threat to the public interest.

A case-by-case approach suggests that projects higher in the processing queue will have a distinct advantage over those behind them. Continued monitoring is necessary as public and private forces continue to put pressure on Congress to expand the list of FTA countries and expedite the approval process for U.S. LNG exports. Meanwhile, industry eagerly waits in hopes of additional approvals.

Greg Matlock is a senior manager in Ernst & Young’s Transaction Advisory Services-Transaction Tax Practice in Houston. He also serves as the tax and transaction advisory services resident for EY’s Global Oil and Gas Center, based in Houston. His practice is focused on energy transactions throughout the various sectors, with an emphasis on oil and gas transactions. Prior to joining EY, Matlock practiced as a tax lawyer at Fulbright & Jaworski LLP (now Norton Rose Fulbright).

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.