Flexible and Transparent Contracts Ease Supply Issues

By Micah Sze

Worldwide shipping container costs are 252% higher than a year ago and 281% higher than five years ago. Despite a full court press, the second busiest port in America, the Port of Long Beach, is struggling to handle an inbound load 23.8% higher than a year ago. Meanwhile, the Port of Los Angeles–North America’s largest port and a critical link for trade between China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and the United States–is experiencing a growth rate of 26%.

Every day, containers are piling up and there is less space for trucks to maneuver, making terminal operators and transportation workers key lynchpins for keeping America’s port operations together.

Port bottlenecks are affecting oil and gas companies’ operations. One of the world’s largest energy service firms missed earnings expectations by more than $100 million in 2020, citing higher prices for materials and chemicals resulting from global supply chain disruptions. The higher costs and longer lead times these disruptions cause can be even more challenging for small independents.

In June, the White House created a supply chain task force to address port backlogs and logistics issues. In November, Congress passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal, which earmarks $17 billion to improve ports and waterways. The package aims to renovate critical port infrastructure and fund construction projects for inland waterways and ports of entry. For example, the port of Baltimore is purchasing additional shipping container cranes and expanding a tunnel from 1895 so shipping containers can be double-stacked on railcars leaving the port.

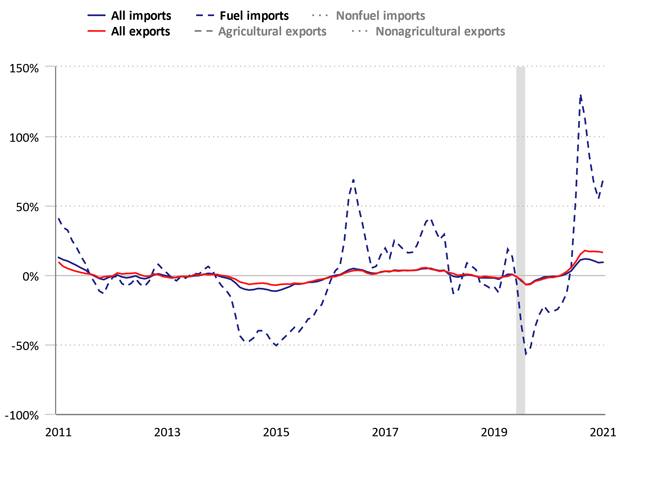

Despite these efforts, costs continue to rise. Overall U.S. import prices have increased by 16.3% since last year, with imported fuel prices increasing by 68.7%, imported petroleum by 70.5% and imported natural gas by 61.7% (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

12-Month Percentage Change In Import and Export Price Indexes

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

While today’s pandemic-induced supply constraints may be unusual, disruptions are not. Producers, upstream service companies and midstream firms have long had to navigate the price increases and supply crunches that often occur when oil field activity jumps. Other industries have also had to grapple with cyclical supply constraints.

There are three proven strategies for mitigating disruptions’ effects.

Help Suppliers Plan

The first strategy is to offer suppliers something they love: certainty. Negotiating lower rates can be difficult when supply chain disruptions have put upward pressure on prices, but we have seen chemical and energy companies cut their rates by offering payment terms that reduce suppliers’ risk. For example, some companies are securing lower rates and preferential treatment for allocations by paying 10%-20% of the contract’s value up front.

To have the flexibility to accelerate payments, buyers need to conserve cash for critical purchases. That can be hard given how many areas most companies would like to invest in, but it can pay off in tough times. One of our client’s suppliers dropped its price by more than 10% and guaranteed delivery by the end of the year–a feat that seems almost impossible in today’s environment–in exchange for a cash payment.

Where possible, consider switching from long payment periods (such as 90 days) to shorter payment cycles with an early payment discount (e.g., a 45-day payment period with a 2% discount if payment is sent within 15 days). The earlier payments put cash in the hands of suppliers, which helps reduce contingencies in suppliers’ pricing by enabling them to secure inventory and hold on to key personnel.

Early payment can yield huge dividends. A leading Fortune 500 company was able to save roughly 7% simply by shortening payment periods from 60 days to fewer than 30.

Shorter pay periods may be difficult for smaller companies who are more price-sensitive and have limited access to capital markets or large balance sheets. However, they still can help their suppliers make sound decisions by communicating their long-term plans and sharing updates when expectations change.

Activity forecasts should be discussed not only with direct suppliers, but also with their suppliers. Several years ago, I helped facilitate meetings between the head of a utility and executives at the United States’ largest construction company. The most valuable portion of those meetings allowed both sides to share their plans for the year. Afterward, the construction company disseminated this information to its portfolio companies and subcontractors. These subcontractors then met with their subcontractors and outlined what they had learned, allowing the overall supply chain to operate with a focused goal in mind.

Use Index-Based Contracts

The second strategy, and one that many buyers and suppliers already have adopted, is to switch from annual fixed price contracts to index or formula-based pricing. The change is particularly beneficial for suppliers with significant commodity exposure, such as ones that provide pipe, valves, chemicals or wire and cable.

Index or formula-based contracts are gaining popularity because they help companies manage long-term risk. Using an index or formula-based contract makes it easy to adjust pricing when underlying commodities change. These adjustments can cause short-term pain, but that pain is worth enduring to avoid locking in pricing for several years when it’s at an all-time high. The adjustments also help ensure suppliers’ margins are healthy enough to support investments in people, research and facilities that ultimately lead to better service.

Supplier health is a real issue. In a survey conducted by Gartner, almost 74% of chief financial officers identified lower profitability as their top concern. This fear is particularly acute for automakers and other manufacturers who face rising subcontracting, labor and direct material costs because of shortages.

Historically, buyers have been able to negotiate contracts that cap price escalations based on inflation. In today’s market, competition for suppliers is fierce enough that buyers have had to remove that cap and adopt an index. Because index adjustments account for market shifts, they can eliminate the need for suppliers to pad proposals with excess contingencies.

Consider a midstream project that required a large purchase of pipe. Lead times were more than six months out and engineering was incomplete, so the amount of pipe needed could not be determined when the contract was being negotiated. Both parties agreed to use an index to establish the cost baseline. The engineering, procurement and construction contractor was then given an incentive to optimize the overall cost and route so the pipeline’s owner and operator could lock in the amount of pipe needed.

Had the pipeline owner insisted on a fixed-price contract, it would have risked locking in prices at today’s all-time highs (Figure 2). Even with U.S. steel production coming back on line–it was at 81.9% capacity as of Dec. 4–it will take time for prices to return to historical levels.

FIGURE 2

Producer Price Index for Iron and Steel Products

Source: The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

For the supplier, a fixed-price contract would have created a strong incentive to pad the proposal 50% or 100% in case material, labor and logistics costs continued moving upward. Instead, the parties opted for a well-structured variable contract that should keep the price reasonable if supplying pipe becomes more expensive but also allow the price to fall if costs ease.

Index-Based Contracts’ Other Benefits

During the past two years, several companies have invoked force majeure to get out of fixed-price contracts. Invocations happened during the pandemic, after the winter storm in Texas, after Hurricane Ida and again after Hurricane Nicholas. While force majeure clauses provide an out, triggering them should be a last resort, as it’s a costly process that usually involves lawyers. Index-based prices can reduce the potential for legal fees while preserving business relationships.

Even if both parties are open to adjusting a fixed-price contract as market conditions change, index-based contracts have a huge advantage: Speed. As they create an index-based contract, the parties agree when pricing should be adjusted and how that adjustment should be calculated. Formalizing these triggers makes the rules clear and obvious. In most cases, when a new index is published, both parties can update and validate their pricing within a few minutes. This is much simpler than negotiating new rates, which often takes weeks of back and forth.

Ideally, an index-based contract will limit risk between customer and supplier or owner and contractor. The key is to use a formula or index that minimizes the external factors the supplier cannot control to reduce or eliminate the need for contingencies.

To deliver fair prices while minimizing risk, the contract must use an index that reflects the structure of the market and key cost drivers. The contract needs to account not only for day-to-day cost drivers but also potential changes, such as tariffs, regulatory shifts or mergers and acquisitions.

Secure Audit Rights

For services whose costs do not have significant commodity price exposure, such as engineering and design, technical consulting and professional services, index-based contracts are not the best means of managing risk and controlling price. Instead, oil and gas companies that need specialized technical labor or highly engineered parts should include audit rights in their contracts’ terms and conditions. The goal is to gain transparency into the underlying cost structure, which will help them manage costs. Many contracts include clauses that allow costs to be clawed back or capped if they get out of hand.

While open book pricing always has been popular in construction, it’s underutilized by oil and gas companies. It can be hard to predict how much projects will cost, especially ones at brownfield facilities where work might lead to the discovery of corrosion or other issues that need to be addressed. A well-run open-book process makes it much easier for both parties to estimate costs and minimize the need for contingencies by forcing them to discuss their assumptions, identify any gaps and flag any risks.

By the end of the contract negotiation, the contract should include all reasonable costs, with the parties vetting their reasonableness. Both parties will have a deeper understanding of the underlying cost drivers, including overhead and profit, as well as the inputs, time and productivity a successful project will demand.

Setting up the first open-book contract for a given type of work is an undertaking, but it can bring enormous benefits, particularly for companies with a portfolio of similar projects. Since open-book audits generate so much data and track actual costs, estimators can find gaps in the original bids and anticipate similar costs going forward.

The strategies I’ve outlined can help companies slash rising supply chain costs. Managing cash for critical purchases can help stabilize operations and even generate savings by enabling companies to give suppliers greater certainty. Shifting to index-based contracts can take away the need for excessive contingencies and boost enterprises’ competitiveness. Lastly, open book pricing can give companies insights that lead to improvements in their cost structures and forecast accuracy.

Micah Sze is a director at GEP, which provides procurement and supply chain solutions to Fortune 500 companies. He leads strategic sourcing projects across several industries, such as chemicals, oil and gas, utilities and energy. Sze’s accomplishments include establishing strategic alliances to replace and repair thousands of miles of gas transmission pipelines, negotiating $100 million in savings for wildfire vegetation management, and managing procurement for thousands of miles of electric transmission and distribution lines across various clients in North America. He also is an inventor with four patents.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.