Market Realities To Determine NGV Growth Rate

By Steven C. Agee

OKLAHOMA CITY–Much has been written about developing compressed natural gas as a transportation fuel. Independent oil and natural gas companies such as Encana, Apache, Chesapeake Energy, Southwestern Energy, Anadarko Petroleum and Noble Energy are leading the way by converting their corporate vehicle fleet as well as drilling rigs and heavy trucks to CNG.

Companies and organizations are discovering that there is a strong economic case for converting company or fleet vehicles, which generally are point-to-point and return-to-home by use and design. The prospects for accelerating natural gas demand with natural gas-powered vehicles appear quite favorable.

This article analyzes the economic, political and logistical/operational feasibility of powering the U.S. consumer/passenger transportation sector with clean-burning, affordable and plentiful domestic natural gas.

Given that the Bureau of Transportation Statistics reports there were more than 250 million registered passenger vehicles in the United States in 2011, and the Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center says only 112,000 were powered by natural gas, the market potential is considerable. The corresponding effect on natural gas demand, and thus prices, could be material, should there be a move by consumers to increase their purchases of NGVs.

Four key issues will be critical for the development and growth of CNG in the consumer/passenger transportation sector:

- What is the current and, perhaps more importantly, the expected price differential between CNG and gasoline/diesel?

- What is the cost of converting a vehicle to CNG, and what is the cost of an original equipment manufacturer (OEM)-produced natural gas vehicle?

- What role are both federal and state governments playing in the NGV marketplace?

- What is the status and expectation for growth in natural gas fueling infrastructure?

Price Differential

The standard unit of measure that equilibrates the energy content of various fuel resources is the gasoline-gallon equivalent. GGE is the amount of alternative fuel it takes to equal the energy content of one liquid gallon of gasoline. Thus, a consumer can compare the energy content of various fuels against that of the most common transportation fuel: gasoline. A GGE of CNG, a GGE of diesel, a GGE of ethanol, and a GGE of electricity all have the same energy content as one gallon of gasoline.

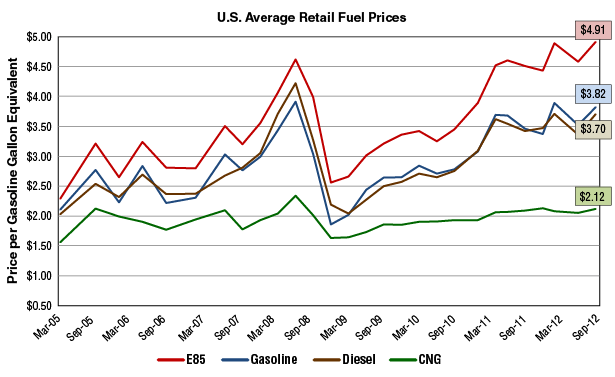

It’s worth noting, for example, that it takes 1.5 gallons of ethanol (E100) to generate the same energy as one gallon of gasoline. Figure 1 provides a picture of U.S. average retail fuel prices, measured in cost per GGE, for E85, gasoline, diesel and CNG from March 2005 to September 2012.

Three things become immediately apparent:

- E85 is priced consistently higher than the other transportation fuels shown in the chart.

- Gasoline and diesel prices generally track each other quite well, although neither is constantly higher or lower.

- Most importantly, the price of CNG was the lowest for the period shown, and since 2009 has been materially lower than the other three fuels.

An important consideration is what the reasonable expectations are for this price differential to continue or, perhaps, even widen. Gasoline and diesel prices, for the most part, are determined by the price of crude oil. As the world continues its recovery from the recession of the past several years, demand for crude oil will increase, exerting upward pressure on gasoline and diesel prices.

Similarly, as the U.S. economy recovers, we should (and in fact already do) see increased demand for natural gas. This will come from electric power generators moving away from coal, and from expanded manufacturing, industrial and commercial use of natural gas.

By itself, this would exert upward pressure on prices. A material move by consumers to purchase NGVs would increase demand for CNG and exert similar upward pressure on natural gas prices.

But there are many other factors that impact the price of both crude oil and natural gas, particularly when one considers supply. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, from September 2005 (before the start of the “great recession”), to November 2012, the U.S. monthly supply of dry natural gas increased almost 50 percent, from 1.3360 trillion cubic feet to 2.001 Tcf. Similarly, monthly production of domestic crude oil increased nearly 64 percent, from 126.3 million barrels in September 2005 to 206.8 MMbbl in November 2012.

These increasing supplies of oil and natural gas, by themselves, act to suppress prices. Unlike natural gas, oil has made a very steady and healthy price recovery since the 2009 recession, and now is forecast to range between $88 and $91 a barrel through December 2014. Given today’s natural gas production levels and volumes in storage, coupled with a very mild winter, natural gas prices appear likely to remain in the $3.70-$4.10 an Mcf range at least through December 2014. An additional source of potential natural gas demand that bears watching is the prospect for exporting liquefied natural gas, which also could act to boost the price of gas over time.

Market Reaction

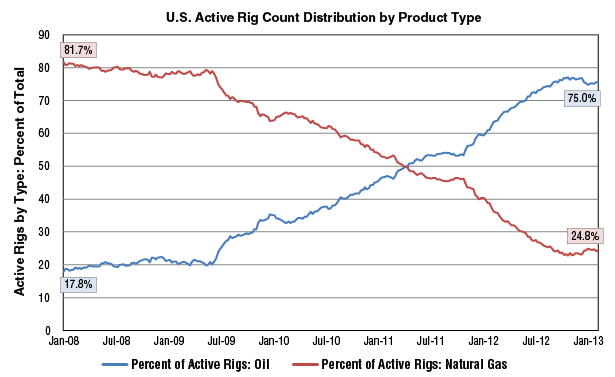

As a result, there has been an enormous shift by domestic exploration companies to search for oil reserves, and away from natural gas. Figure 2 depicts this material change using data from the Baker Hughes rotary rig count as a proxy for oil versus natural gas exploration efforts.

The point of this discussion is simply that the economic environment is not static. Markets continually adjust to price signals. When oil and natural gas prices peaked in 2008, there were massive capital flows into industry, which resulted in increased risk-taking behavior in developing unconventional resources plays–primarily shales–and experimentation with hydraulic fracturing techniques that have unlocked game-changing new supplies of both oil and natural gas.

New supplies came on line and prices fell. Oil prices have recovered, but natural gas prices haven’t yet. However, with the shift in exploratory efforts directed toward oil, one can argue that over time, natural gas production will stabilize, or perhaps even fall, until the economy recovers and prices rise to a level attractive to natural gas producers.

At the same time, should domestic crude oil production continue to increase, given this shift to drilling oil prospects, and should the Keystone XL pipeline from Canada ultimately be given the green light and more Canadian oil begins moving into the U.S. market, we could see downward pressure on oil, and thus gasoline and diesel prices. Given time–and we don’t know how long that will take–oil and natural gas prices may adjust and the price differential between gasoline and CNG could narrow.

Rational consumers, thinking long term, may want to factor in this potential narrowing of the price differential when considering retrofitting existing vehicles or purchasing OEM CNG vehicles.

In addition, even if the price differential between CNG and gasoline/diesel remains large, a consumer may need to drive a significant number of miles to achieve a reasonable payout for the upfront costs involved in acquiring or converting to a CNG vehicle.

OEM Versus Conversion

Natural gas has been used in the transportation sector as a motor vehicle fuel since the 1930s. Ford, General Motors and Chrysler have produced passenger vehicles fueled by CNG–primarily for fleet vehicles–for decades. But over time, particularly in the 1970s and ’80s, fewer CNG-powered vehicles were produced because the price and supply of natural gas were in question, and focus increased on electricity, ethanol, and other alternative fuels.

Domestic automakers essentially withdrew from the NGV market because of slow sales, financial challenges, and the limited CNG fueling infrastructure. Consumers interested in NGVs essentially had one choice. Honda has offered a CNG version of its Civic since 1998, and it began marketing its latest CNG sedan nationwide last year, again based on the Civic.

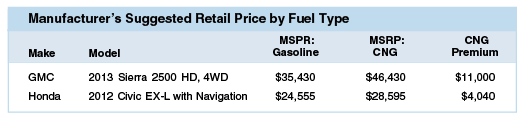

With regard to the cost of an OEM natural gas vehicle versus a gasoline model, it is clear there is a premium for the NGV vehicle. The principal cost difference in constructing natural gas vehicles is the fuel tank. Natural gas and gasoline engines are quite similar, but natural gas requires a storage tank that must be stronger, heavier and larger, given the high-pressure requirements of storing natural gas.

Table 1 shows the manufacturer’s suggested retail price for two vehicles produced to run on either gasoline or CNG and the corresponding premium charged for the CNG model as of Jan. 22, 2013.

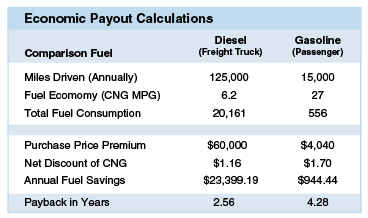

Using the smaller, $4,040 premium for the Honda Civic, Table 2 provides an interesting payout comparison with a freight truck fleet vehicle powered by diesel.

It has been demonstrated that fleet vehicles driving point-to-point and return-to-home can save money and achieve a reasonable payout using CNG versus diesel. Table 2 demonstrates that for a fleet/freight truck that drives an average of 125,000 miles a year, with an average of 6.2 miles per CNG-gallon equivalent (CNG MPG) and a $60,000 purchase price premium, the payback is two and a half years.

Using a similar analysis and assuming a consumer averages 15,000 miles of driving a year, with a city CNG MPG (according to Honda) of 27 and the $4,040 price premium, it would take 4.28 years to pay out the price differential. Clearly, the critical variable is the number of miles an individual drives.

As an alternative, a consumer may choose to convert a gasoline vehicle to CNG, but this can be expensive and there are other negative externalities, including loss of trunk space. There are federal and state tax incentives for conversion, but the conversion still requires Environmental Protection Agency certification (by the entity providing the conversions) to qualify for the tax credits. Obtaining this certificate can be expensive (tens of thousands of dollars) and can take as long as six-eight months.

In addition, installing a CNG conversion kit in a gasoline-powered vehicle generally means sacrificing a large part of the vehicle’s trunk or cargo space. If NGVs take market share from gasoline- and diesel-powered passenger cars, it is much more likely this will occur with OEMs rather than conversions.

Role Of Government

At the federal level, the American Taxpayer Relief Act passed by Congress early this year extended a $0.50-a-gallon tax credit for compressed natural gas vehicles. While it is in effect, this credit will act to increase the price differential between CNG and gasoline or diesel, making CNG more attractive as a transportation fuel, particularly for fleet vehicle owners.

Another issue that needs to be monitored at the federal level is the role the EPA plays in regulating hydraulic fracturing. Any federal regulations that would effectively limit hydraulic fracturing could reverse the course of opening new supplies of domestic energy resources and drive up the price of natural gas, crude oil, gasoline, diesel and other refined products. However, this type of action may not affect the price differential between natural gas and gasoline, since it likely would limit exploration and production of both crude oil and natural gas.

At the state level, a remarkable energy policy was developed in 2011 by Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, which became known as the Oklahoma First Energy Plan. This is a comprehensive plan designed to promote all forms of energy production, support and encourage energy efficiency, and assist in training a highly skilled workforce for energy-related jobs.

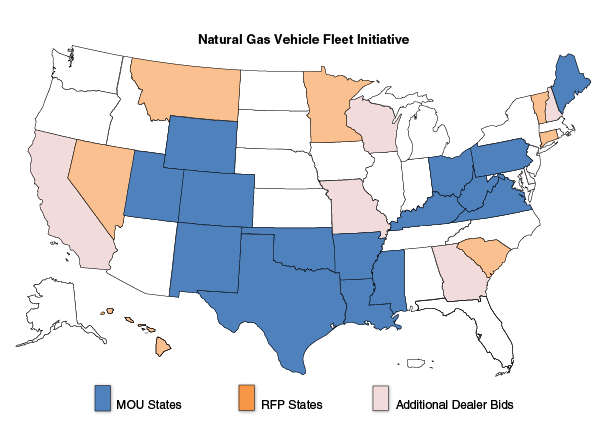

The cornerstone of this plan, announced at the November 2011 Governor’s Energy Conference, was an aggressive push to boost CNG infrastructure through a bipartisan, multistate initiative. A memorandum of understanding was signed on Nov. 9, 2011, by Governor Fallin and Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper. Subsequently, 13 additional governors have executed the agreement.

This initiative calls for these states to commit to purchasing NGVs for their state fleets. The goal is to purchase, as a group, a minimum of 5,000 NGVs a year, which would help incentivize automobile manufacturers to begin producing affordable natural gas vehicles.

During 2012, Governor Fallin and Oklahoma Energy Secretary Michael Ming announced that more than 100 bids had been submitted from dealers in 28 states. Figure 3 provides details.

This is a commendable effort by Governors Fallin and Hickenlooper, and is designed to not only boost demand for NGVs, but in turn, should promote private sector development of natural gas fueling infrastructure. In signing the initiative, Governor Fallin stated, “By supporting natural gas production and consumption, we are supporting an environmentally friendly, American energy resource. Not only will that bolster our economic security by creating jobs, it will improve our national security by helping to wean the United States off foreign oil.”

Oklahoma also provides a 75 percent tax credit for the cost of building CNG fueling infrastructure to qualifying companies, provided they have sufficient tax liability to be offset by the credit.

Fueling Infrastructure

The pace of infrastructure build-out for CNG stations nationwide will be slow. According to Love’s Travel Stops & Country Stores, “The typical footprint for a CNG station is a 20- by 60-foot rectangle for equipment. Capital costs range from $1.25 million to $1.75 million at a given location, not including pipeline improvement costs, if needed.”

Love’s says there is insufficient CNG traffic (nationwide) today to warrant such a capital expenditure in its 300-station, 40-state service area. There are, however, isolated markets–almost entirely related to freight trucking–within large metropolitan areas, point-to-point, return-to-home, and a few regional (triangulation) traffic patterns that are under consideration for CNG stations.

This points to the network externality (chicken/egg) problem. The market for CNG likely would benefit from government intervention, as Oklahoma is doing, not only to increase demand for CNG vehicles, but also to help jump-start infrastructure build-out.

As the U.S. economy grows, the demand for natural gas will continue to grow for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is electric power generation. However, the transition from gasoline and diesel to natural gas as a transportation fuel will be slow. Although it has been argued that using natural gas as a transportation fuel makes economic sense, particularly for fleet vehicles, it will require another important element for this transition to occur with consumer/passenger vehicles.

It is a basic tenet of human nature that behavior is hard to change. A brilliant idea or a cheap, affordable economic solution to a problem may be identified, but if it requires people to change behavior, it may not work.

Educating consumers about the economics of natural gas as a transportation fuel will take time. Educating them about safety, fueling station infrastructure, and how to properly fuel a natural gas vehicle will take time. Educating them about the possibility of having their own home natural gas fueling equipment and the costs of such a delivery system will take time.

Those states that have abundant sources of natural gas and companies that promote its use, will take the lead in this transition because of their familiarity with the economics, handling, and infrastructure. But if the price differential between gasoline/diesel and natural gas persists, or even widens, and the fueling infrastructure is built, there will be a transition and natural gas will see an increasing role as a transportation fuel.

Steven C. Agee is dean and professor of economics at Oklahoma City University’s Meinders School of Business, and is an economist specializing in energy policy, banking, monetary theory and macroeconomic policy. He also is president and chief operating officer of Agee Energy LLC. Prior to forming his company in 2006, Agee served as president and COO of XAE Corporation from 1982 to 2005, and as president and COO of Lee & Agee Inc. from 1988 to 2006. He serves on the Coppermark Bank Board of Directors, as well as on the boards of the Oklahoma City Philharmonic Foundation, Allied Arts, and Oklahoma City Community Foundation. He served six years on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Oklahoma City Branch, including three as chairman. Agee has a B.B.A. in economics from the University of Oklahoma, and an M.S. and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Kansas.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.