Global Markets

New High Expected In Deepwater Liquids Output

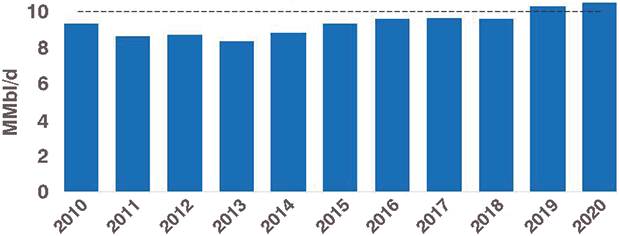

As the international offshore market continues to recover, Rystad Energy says it expects global deepwater liquids production to jump to a record level in 2019 after three consecutive years of stagnant production growth.

Driven by new field startups in the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil, the company says total deepwater liquids volumes will reach 10.3 million barrels a day by year’s end, representing an increase of 700,000 bbl/d compared to 2018 (Figure 1).

Meantime, a report from Wood Mackenzie forecasts “smoother sailing ahead” for the offshore upstream supply chain with increased demand for equipment and services as more final investment decisions are made to move offshore projects forward.

A case in point is the subsea sector, where Mhairidh Evans, a subsea supply chain principal analyst, says activity has already markedly picked up. Wood Mackenzie estimates a 40 percent year-over-year increase in 2018 in international demand for subsea equipment and services.

“Demand for subsea equipment is one of the best leading indicators of offshore market activity,” she relates. “It is likely that demand will remain steady for the next few years, averaging about 300 subsea trees per year–an encouraging sign for the sector.”

Offshore projects remain leaner and phased, with the focus on compact, modular and standard solutions as operators seek the shortest cycle times. “While the subsea market as a whole still remains oversupplied, another busy year in 2019 will change that,” Evans observes. “We think the window of opportunity to lock in preferential conditions in 2019 is dwindling, and this will be more pronounced as we edge closer to 2020.”

Noting that total global subsea manufacturing capacity has been reduced by 25 percent compared to 2014, she says, “The result is manufacturing plants that can tighten much quicker than before, even with the smaller, more efficient operations that today’s projects demand . . . Procurement teams and category management will need to strategize internally and with their preferred suppliers, preparing for anticipated price inflation and potentially increased lead times.”

Meantime, demand for floating production, storage and offloading vessels (FPSOs) also should be on the rise, according to Catarina Podevyn, a senior research analyst at Wood Mackenzie. As with subsea solutions, she says the industry continues to focus on adopting modular and standardized FPSO designs.

“Overspending is a thing of the past. Despite the market’s recovery, we expect development budgets will have to stretch farther than ever,” she comments. “We can expect to see alternative contracting models that reduce technical and financial risk to operators and optimize efficiency.”

That includes a higher uptake of the build-own-operate-transfer (BOT/BOOT) contract models. With this approach, operators lease an FPSO at a higher rate before buying it outright. “This frees them from the upfront financial risk that would normally accompany a turnkey approach,” Podevyn explains. “Contractors, however, take on project execution risk and must hit deadlines or face losses. We expect this will prompt more subcontracting, particularly with many FPSOs nearing award.”

On the drilling side, Wood Mackenzie Principal Analyst Leslie Cook says the offshore floating rig segment has been a buyer’s market, with operators holding contracting power for all but the ultradeepwater, harsh environment rigs, where supply is limited. According to Cook, day rates for floating rigs will remain low through most of 2019, although signs are emerging that indicate the potential for higher demand and higher day rates starting in the latter part of 2019.

“Because of low day rates, drilling contractors have preferred short-term contracts, hesitating to lock in assets on longer charters. Market utilization hovered near 65 percent on continued rig oversupply. This, coupled with rig owners needing to bid aggressively for contracts or else see their assets idle, will keep rates for most rig types low.

“However, exploration is increasing. That, together with the likelihood of further consolidation among rig contractors and older assets being taken off the market, should drive market fundamentals to a point where day rates begin to rise appreciably toward the end of the year,” Cook comments. “We expect the rig market to balance out in 2020.”

Oil Supply Outlook

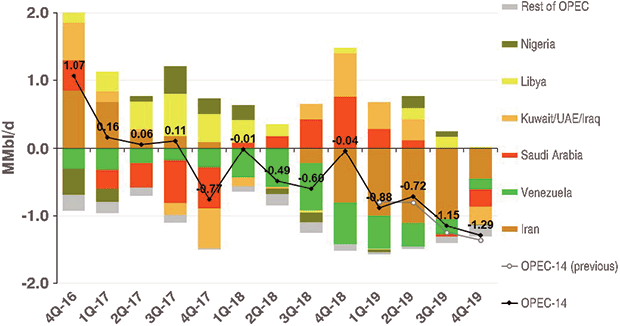

Turning to the broader oil market, Rystad Energy predicts that the combined production of the 14 OPEC member countries will drop to 31.1 million bbl/d on average in 2019, significantly below its quota target of 31.9 million bbl/d under the current OPEC+ deal (Figure 2). Under the agreement, OPEC agreed to cut 800,000 bbl/d from the October reference level of 32.7 million bbl/d.

“Our projection is based on the assumption that Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Iraq target their own quotas instead of compensating for Iran and Venezuela during the first half of 2019, and that OPEC+ production cuts are extended through December,” the report reads. “OPEC will be able to balance the market if members stick to their own quotas and the deal rolled over to December.”

Rystad says it does not expect waivers on U.S. sanctions of Iranian oil exports to be extended past May, leading to Iranian supplies dropping by 265,000 bbl/d by June. “For the first half of 2019, we expect KSA, UAE and Kuwait to comply 100 percent with their country quotas, while Iraq reaches full compliance by April. For the second half of 2019, we expect KSA, UAE, Kuwait and Iraq to compensate for additional losses from Iran, but still restrain output in order to balance the market.”

Nigeria is expected to keep production fairly flat from October 2018 levels, and Libyan production is forecast to average 1.04 million bbl/d in 2019 compared with the 1.12 million bbl/d last October. Output from the remaining OPEC members is largely driven by natural declines with limited upside, making output policy discussions less relevant, Rystad says.

The political crisis in Venezuela–one of OPEC’s founding members–has dominated headlines since early January, but the country’s oil production has been in a freefall for some time and that trend will carry over into 2019 and 2020, according to a Rystad Energy analysis released on Feb. 11. Rystad projects that Venezuela’s already sinking oil production will drop by another 340,000 bbl/d this year and slide even farther next year.

In fact, total output could fall as low as 680,000 bbl/d in 2020 if the political status quo continues and Venezuela is unable to offset the effects of U.S. sanctions and secure new financing. On the other hand, Rystad’s “high case” scenario considers the effects of a regime change where U.S. sanctions are lifted and new financing agreements are secured. Under that scenario, production would average 1.06 million bbl/d in 2020.

One critical factor is Venezuela’s reliance on diluents (naphtha) imported from the United States to mix with the heavy crude produced from the Orinoco Belt in order to make the oil marketable, points out Paola Rodriguez-Masiu, a Rystad Energy analyst. Venezuela has been importing 60,000 bbl/d of naphtha from the United States, mainly from Citgo, the U.S. refining subsidiary of state oil company PDVSA.

“Rystad Energy forecasts that some operators in Venezuela will run out of the crucial diluent by March. Without diluent, 200,000 bbl/d of heavy crude exports are at risk,” Rodriguez-Masiu says.

Accelerating Decline

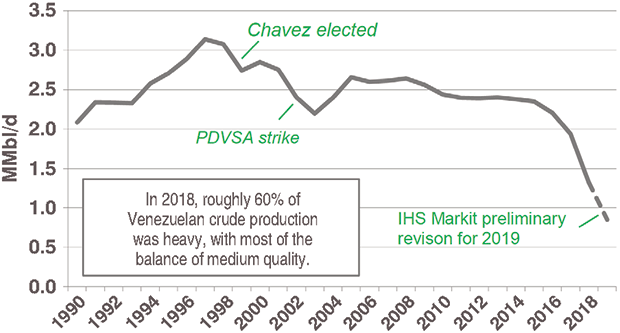

A new report from IHS Markit says the longer the faceoff lasts between Juan Guaido, the U.S.-backed head of the Venezuelan National Assembly, and Russia-supported President Nicolas Maduro, the greater the likelihood of an acceleration in the already steep decline in Venezuelan oil output.

At issue is the country’s 2018 presidential election, which Maduro claims gave him a new six-year term after his previous presidential term expired on Jan. 10. Jim Burkhard, IHS Markit vice president of oil markets research, explains that the election violated Venezuela’s constitution. “In this case, the presidency is currently vacant, and the head of the National Assembly (Guaido) assumes the office until legitimate elections install a new president,” he explains.

In response, on Jan. 28 the United States imposed import sanctions on Venezuelan oil. The sanctions effectively reduce U.S. Venezuelan imports to zero from recent levels of 500,000–600,000 bbl/d, and cut off diluent supply from the United States for blending extra-heavy crude oil into Venezuela’s diluted crude oil (DCO) grade, according to Burkhard.

U.S. sanctions, combined with the limited fungibility of Venezuela’s extra-heavy crude and the burden of paying loans with oil shipments to China and Russia, point to a sharp decline in Venezuelan oil revenues and exports, Burkhard offers, and to an even more severe breakdown of Venezuela’s reeling oil industry.

By IHS Markit’s count, Venezuela’s daily oil output fell by 500,000 bbl/d in 2018 to an average of 1.1 million bbl/d. That was roughly half the nation’s average production in 2015 and only one-third of its peak output in the mid-1990s prior to the election of former President Hugo Chavez (Figure 3). IHS Markit forecasts that daily production will dip below 1 million bbl/d in 2019.

“Although there is much uncertainty . . . our preliminary thinking is Venezuelan production could fall to the 700,000–900,000 bbl/d range in the coming months,” Burkhard reveals. “A reversal of Venezuela’s declining output will require money, expertise, equipment, security and time. The 20-year brain drain from the oil industry cannot be rapidly overcome.”

Noting that the United States is the world’s largest market for heavy oil, accounting for more than half of global heavy crude demand, Burkhard says it remains uncertain how much of the 500,000-600,000 bbl/d of U.S. imports will be absorbed by other buyers and the discounted pricing points at which that might happen.

“PDVSA will be under pressure to offer price discounts and face higher transportation costs if it is to find enough buyers to offset the loss of the U.S. market. Oil provided to China and Russia does not generate cash for PDVSA, but provides payback for loans. Will PDVSA want to divert previously cash-generating exports to pay down loans, especially when the current regime needs cash to survive?” he posits.

Aside from the United States, China and India are the other two major destinations for Venezuelan crude. Even if there is appetite for more heavy Venezuelan oil in China or India, Burkhard points out that PDVSA uses facilities owned by U.S. entities on nearby Caribbean islands to export some of its oil. “PDVSA may no longer be able use these facilities,” he reasons.

While Burkhard suggests that U.S. sanctions by themselves will have minimal implications for the global oil market, he says the larger issues of Venezuela’s long-term production declines and ongoing political chaos add uncertainty to the supply outlook.

“The U.S. ban is not a major global oil supply shock,” he concludes. “(But) in terms of overall global oil supply–of all grades–there is currently about 2.2 million bbl/d that is off the market owing to U.S. sanctions on Iran, Vienna Alliance production cuts, and the Alberta curtailment. Venezuela could make this number bigger, as could a May reduction in waivers granted to import Iranian crude. The ingredients for severe oil price volatility remain in place. Perhaps even more so now.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.