Crude By Rail

Railroad Oil Shipping is Here to Stay

By Kevin Birn and Juan Osuna

HOUSTON–The volume of crude oil shipped on U.S. and Canadian railroads has grown tremendously over the past few years. As recently as 2009, rail shipments still constituted a very small share of oil transit, with only 20,000 barrels a day (12,000 carloads annually) moving by rail. That represented 0.01 percent of all crude oil delivered to North American refineries that year. In 2013, more than 950,000 bbl/d (540,000 carloads annually) were transported by rail, accounting for nearly 9 percent of total North American production.

Compared with pipelines, transporting crude by rail generally involves more parties. Oil is transported from the field to a loading terminal by pipeline and/or truck, and shippers can be producers, refiners or third-party marketing agents. Loading/unloading terminal operators are responsible for the proper loading and unloading of tank cars. It is the responsibility of the terminal operator to ensure that crude oil is loaded into appropriate tank cars in accordance with hazardous material regulations, and that cars are properly labeled. Most crude oil loading terminals are owned by third-party companies, but some are owned by producers or refiners.

Tank car owners are responsible for ensuring that their cars meet regulatory standards. Historically, about 75 percent of the cars in North America are owned by third-party leasing companies. Shippers, receivers and railroads also own tank cars. The railroads are responsible for the safe transport of the crude to market, including ensuring that tracks and equipment are properly maintained.

The North American freight rail industry consists of seven Class 1 (long-haul) railways and more than 500 short-line operations. In the United States, freight rail is dominated by four large Class 1 networks, two of which are concentrated in the east (Norfolk Southern and CSX Corporation) and two in the west (Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Union Pacific). Kansas City Southern is the other U.S. Class 1 railway, with a network stretching from the Midwest to the Gulf Coast and into Mexico. There are two transcontinental networks in Canada (Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway), both of which have significant operations in the United States.

Shipping crude oil has become an important part of North American railroad operations, and is integral to delivering crude oil to market as well as transporting equipment, pipe, proppant and other goods required to support oil production. However, uncertainty surrounds the outlook for crude-by-rail volumes in North America. Key areas of that uncertainty include the timing of new pipeline capacity, the extent of production growth in tight oil plays, current lower oil prices, and regulatory factors.

Several large proposed pipeline projects and expansions exiting western Canada and North Dakota could be online in 2016-19. Since moving crude by pipeline is less expensive than moving by rail, the addition of new pipeline capacity should contribute to the peaking of crude by rail movements at around 10 percent of total North American production.

Bakken Rail Shipments

Most crude-by-rail movements in North America occur in the United States, and the majority of those movements come from North Dakota. Production from the Bakken/ Three Forks tight oil play expanded nearly 500 percent between 2009 and 2013, and with limited access to pipelines and a lack of local refining capacity in the Williston Basin, much of that incremental growth has ended up on the rails. In fact, more than 75 percent of all U.S. rail shipments of crude oil originated in North Dakota in 2013, with more than 50 percent of those shipments terminating in the Gulf Coast.

In August 2014, shipments of crude oil departing North Dakota by railroad averaged 765,000 bbl/d. However, the destination is increasingly shifting toward the East Coast, West Coast and even Midwest as growing production volumes from the Eagle Ford and Permian Basin displace North Dakota production in Gulf Coast refineries. The East Coast market is a particularly good fit for Bakken production, with a number of refineries not connected to pipelines and designed to run imported light crude oil. In 2014, these East Coast refineries collectively consumed about 1.3 MMbbl/d of light, sweet crude oil, making them a natural match for the oil produced from the Bakken/Three Forks play.

The trajectory of all U.S. crude-by-rail volumes is difficult to predict because inland oil transportation is becoming increasingly complex. Pipeline, rail, barge and marine tankers all will be leveraged. Looking further ahead into 2016 and beyond, the outlook for North American crude-by-rail is uncertain, with opposing forces at work that will shape future demand.

Before oil prices declined in late 2014, IHS had anticipated that a combination of new pipelines, a rise in regional refinery demand, and moderation in oil production growth would lead to a peaking of crude rail movements between 2015 and 2016 near 1.5 MMbbl/d (an increase of nearly 400,000 bbl/d over 2014).

Lower-than-anticipated production would lead to the peaking of rail crude transport sooner and at a lower rate. However, the outlook is also linked to the timing of new pipelines. Should pipeline projects meet delays, greater incremental production growth could end up on the rails, pushing crude-by-rail demand higher. With so much uncertainty surrounding oil markets and pipeline timing, it is not yet clear how these factors will ultimately play out.

Here To Stay

Regardless of when shipping volumes peak, oil transportation by railway is here to stay. The revival of shipping crude on railcars is still in the early days, and unconventional oil resource plays are expected to provide opportunities for crude to move by rail for many years to come. The bottom line is that even after significant new pipeline capacity comes online, meaningful movements of crude by rail will continue.

However, as the volume of crude oil moving by rail has increased, a number of accidents have been reported, increasing safety concerns. With even greater rail movements of crude oil expected, regulators are seeking ways to further enhance transportation safety. This effort also encompasses ethanol, of which 250,000 bbl/d (390,000 carloads) were shipped by rail in 2013. A number of measures have been proposed on both sides of the border that could impact future movements.

Those measures include announced plans to phase out 72,000 U.S. Department of Transportation 111 (DOT-111) tank cars–the workhorse of the North American tank car fleet–in favor of the CPC-1232 (TP14877 in Canada) car design. DOT-111 general-purpose tankers are designed to carry both nonhazardous and hazardous liquids, and are the most common tank car specification in North America. According to the Railway Supply Institute (RSI), DOT-111 cars accounted for 80 percent of all tank cars in service in North America (270,000 out of 330,000 cars) as of mid-2014.

The CPC-1232 is a newer design DOT-111 that has been built since November 2011. It comes in various sizes up to 30,000 gallons and has a greater maximum weight capacity. It also includes a number of safety improvements, including partial head shields, insulation, and protection for the top fittings used to load/unload cars and provide pressure relief.

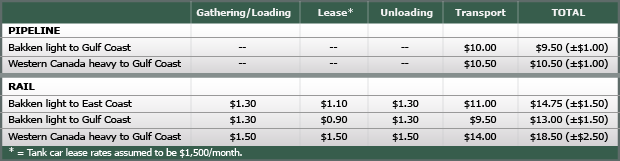

Phasing out older oil tank cars at a time when they are in high demand may place even greater upward pressure on tank car prices. Table 1 compares costs for shipping crude by rail versus pipeline, including average estimates for loading/unloading tank cars at rail terminals, leasing or financing tank cars, and railroad transport charges.

Although pipeline shipping continues to have an advantage over rail in terms of cost, transporting crude by rail has become more efficient over the past few years. Compared with early 2013, costs associated with transit times and gathering/loading have declined. Using unit trains also is reducing costs, allowing shippers to transport more crude oil and deliver it more rapidly with less handling (starts, stops and switching of cars).

The future of oil-by-rail is going where pipelines do not or cannot go. The ability of railroads to connect producers with remote refiners and readily load production in areas where pipelines may be challenged to reach makes rail a permanent feature of delivering inland crude oil production to North American refiners.

Editor’s Note: The preceding article was summarized from an IHS Energy report issued in December, Crude by Rail: The New Logistics of Tight Oil and Oil Sands Growth. The co-authors acknowledge IHS colleagues Carmen Velasquez, Jeff Meyer and Steven Owens, as well as Malcolm Cairns, principal of Malcolm Cairns Research & Consulting, for their contributions to the report.

KEVIN BIRN, director, IHS Energy, is part of the IHS North American crude oil markets team and leads the IHS Energy Oil Sands Dialogue. His expertise includes Canadian oil sands development, infrastructure, crude oil markets, crude-by-rail, crude oil life cycle analysis and Canadian energy policy. Prior to joining IHS, Birn held various senior advisor positions in Canada’s Department of Natural Resources, where he was involved in a number of energy issues. He holds undergraduate and graduate degrees in business and economics from the University of Alberta.

JUAN OSUNA is senior director at IHS Energy Insight. His expertise encompasses oil transportation, marketing, and market fundamentals. Osuna has worked in the energy industry for 10 years, and worked in commodity forecasting and business development at Enbridge Pipeline before joining IHS. He holds an undergraduate degree from the Universidad Rafael Urdaneta in Venezuela and a graduate degree in communication from the University of Calgary.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.