Shale Gas, NGLs Fuel Large-Scale Petrochemical Investments

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

The Ides of March were good to the Marcellus Shale play this year, with Shell Chemical signing a site option agreement on March 15 to construct a petrochemical complex with a “world-scale” ethane cracker in Potter and Center townships in Beaver County, Pa., near Monaca, about 20 miles northeast of Pittsburgh on a bend in the Ohio River.

The company released a statement saying the complex included a steam cracker to turn ethane produced from the Marcellus into ethylene and other petrochemical building blocks. In addition to the cracker, Shell said in the release that it was “also considering polyethylene and monoethylene glycol units to help meet increasing demands in the North American market. Much of the polyethylene and monoethylene glycol production will be used by industries in the Northeast.”

No capacities were given for the various chemical production units, nor did the company specify a date for groundbreaking or commencing operations at the complex. However, the Shell announcement provides evidence of how downstream industries–from chemicals to fertilizers–are moving to take advantage of the bonanza of feedstocks coming out North American unconventional gas plays.

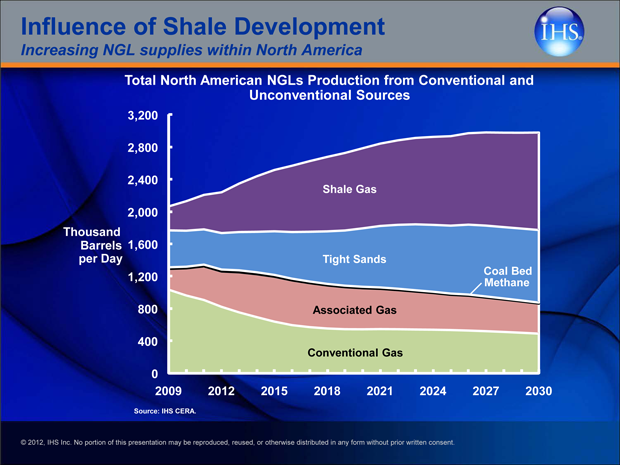

FIGURE 1

Total North American NGL Production from Conventional and Unconventional Sources

Source: IHS

“Bs” have long been industry shorthand for billions of cubic feet of natural gas, but now that so many Bs are flowing out of unconventional plays, Bs also stand for billions of dollars in downstream investment in nonfuel uses for natural gas and associated liquids. Reversing the trend through the better part of the past decade, when historically high natural gas prices led to an overseas exodus of industrial and manufacturing users–especially petrochemical companies–that depend on gas as a feedstock, huge capital investment projects are now on the books that will effectively bring lost petrochemical demand back to the North American market.

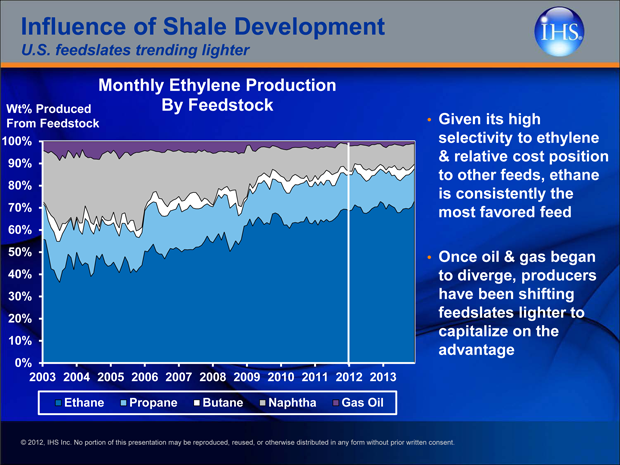

Reflecting the trend lines on increased U.S. crude oil and dry gas production, Figure 1 shows the actual and projected increase in total North American natural gas liquids production from both conventional and unconventional sources. Figure 2 shows monthly U.S. ethylene production by feedstock.

Fundamental Change

Use as a fuel directly and to generate power remain by far the primary markets for natural gas, but the shale revolution has wrought fundamental change in the upstream market. Chemical companies across North America are beginning to believe in the new reality of plentiful and reasonably priced natural gas.

Methane is not simply for turning generators and heating soup on the stove, it is also the feedstock for methanol and ammonia. The main market in North America for ethane is as feedstock for steam crackers to make ethylene, according to NGL marketers. That, in turn, is made into polyethylene (used in everything from milk jugs to plastic wrap) or other derivatives, including ethylene glycol (used as an engine coolant or as a precursor to a variety of polymers).

Propane and butane are mostly fuels, but the shift in steam cracker feedslates from naphtha and mixed natural gas liquids to primarily ethane means more ethylene out of the other end, according to chemical companies. However, it also means they make fewer key co-products, especially propylene and butadiene. Several chemical companies report they are investing in commercial dehydrogenation technologies to produce propylene from propane and possibly butadiene from butane. Other firms say they are exploring methanol-to-olefins and other such building-block conversions.

Propylene is used primarily for polypropylene, another high-volume thermoplastic. Butadiene is an essential component in elastomers. Most tires are styrene butadiene rubber; styrene is made from ethylene plus benzene (ethyl benzene). Polystyrene is the third major thermoplastic, used for cups, plates and other items. Its distinctive smell is known to legions of men who built plastic models as boys.

Much of the chemistry involved was pioneered in North America as part of the war effort in the 1940s. Over the past few decades, the United States lost much of its competitive advantage in commodity petrochemicals to regions such as the Middle East as oil and gas exporting countries sought to gain value by expanding their own downstream industries.

New Methanol Hub

As if to signal the dawn of a new era, the largest methanol producer in the world, Methanex Corporation, said early in January that it would relocate at least one of its idle trains from its complex in Cabo Negro, Chile, to an existing facility near Geismar, La. Site-specific engineering has begun, and the 1 million metric ton-a-year plant is expected to be operational in the second half of 2014. Early in February, Jacobs Engineering was awarded the contract to reconstruct the Geismar plant.

At the time of the announcement, Bruce Aitken, president and chief executive officer of Methanex, commented, “The outlook for low North American natural gas prices makes Louisiana an attractive location in which to produce methanol. It is also a large methanol-consuming region, possesses world-class infrastructure and skilled workers, and is a positive environment in which to do business.”

He added, “This project represents a unique opportunity in the industry to add capacity at a lower capital cost and in about half the time of a new ‘greenfield’ methanol plant. The timing of this project is excellent; there is strong demand growth for methanol globally and there is little new production capacity being added over the next several years.”

The Methanex plant is one of several that will increase North American methanol capacity by 158 percent to 3.48 million metric tons annually by 2014, according to Dewey Johnson, senior director of chemical market research at IHS Chemical in Houston.

It takes 32 MMBtus of natural gas to make one metric ton of methanol, so 3.48 million metric tons of methanol requires 111.36 trillion Btus (111.36 Bcf) of gas, says Johnson. By itself, increased methanol output is not enough to move the needle on U.S. gas prices, but he notes that it is certainly a significant new source of demand. Also, he points out, it is growing primarily in an existing petrochemical region, so transportation and processing capacities are not in question.

Beyond the known methanol additions, there are likely to be further gains, Johnson says. “North America is a net importer of methanol. As domestic production expands, methanol imports will be displaced, particularly from higher-production cost regions such as China.”

The Big Driver

“Methanol and fertilizer from methane certainly are important end-use markets, but we look mostly at olefins, ethylene and co-products, and their derivatives,” says James Cooper, vice president of petrochemicals for the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) Association, a trade group representing companies in the petrochemical and refining sectors. “Ethylene is the big driver. It and its derivatives are ubiquitous in American and global manufacturing. They are not simply in plastics, but also in specialty chemicals and even pharmaceuticals.”

For chemical producers, the shale gas boom has surpassed being merely a benefit to becoming a fundamental change in their business. “Shale gas and the associated NGLs are a game-changer for our members,” says Cooper. “We are reading on a weekly basis about expanded production and new chemistries based on this new supply of energy and feedstocks.”

The association’s name itself reflects the changing importance of chemicals in the American manufacturing base,” Cooper notes. “Before this year AFPM was the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association. That name is only a few years old and was a change from National Petroleum Refiners Association.

“The producers tell us that natural gas is affordable and plentiful, not just today, but on a structural and strategic-planning level. We expect it to be a dependable source for a long time,” Cooper continues. “In only the past year, four or five major companies have announced billion-dollar plus investments either in the new gas producing areas, or in pipeline connections from those to our association members. I have not heard this much excitement in our industry in many years.”

Two of those pipelines will transport ethane from Pennsylvania to major petrochemical centers. Last year, Sunoco inked a deal to move ethane from the Marcellus to Nova Chemical’s giant complex at Sarnia, Ontario. Then in January, Enterprise Products Partners confirmed plans to build a 1,230-mile line from Pennsylvania to the Gulf Coast, to begin commercial operations in the first quarter of 2014.

The Appalachia-to-Texas, or Atex line, will be built with an initial capacity of 190,000 bbl/d of ethane, and transport rates will start at $0.15 a gallon, according to Enterprise reports. Chesapeake Energy will be the anchor shipper, having committed to 75,000 bbl/d over the first five years, the company says.

The Atex line will run from Washington County, Pa., through 600 miles of new pipe to Cape Girardeau, Mo. There, Enterprise says it will reverse an existing line and adapt it to transport ethane to the Gulf Coast, connecting to a new spur to Enterprise’s NGLs storage complex at Mont Belvieu, Tx.

Carlo Barrasa, director of NGLs and cracker economics at IHS Chemical, estimates total U.S. ethane consumption is a little less than 1 million barrels a year, and has been growing strongly since 2006. “Five years ago, cracker feeds were about 40 percent ethane,” he says. “Today, feedslates are 70 percent ethane, and that will continue to creep higher every year. Clearly, olefins producers are going as light as possible on feedstocks.”

Barrasa notes that at $0.44/gallon for ethane, the production cost for ethylene comes to $0.18/pound. “The market price for ethylene is about $0.70/pound, so cracker operators are experiencing a tremendous profit margin right now,” he observed in March. “They are taking any opportunity to optimize their trains to consume ethane.”

Marcellus Crackers

In June 2011, Shell announced that it was developing plans to build a large steam cracker with integrated derivative units in the Appalachian region. “Building an ethane-fed cracker in Appalachia will unlock significant gas production in the Marcellus by providing a local outlet for the ethane,” says Ben van Beurden, Shell’s executive vice president for chemicals. “This fits well with our strategy to strengthen our chemicals feedstock advantage and would be another step in growing our chemicals business to meet increasing demand.”

Shell says it expects North American demand for polyethylene to grow, so the economic and efficiency benefits of a regional cracker make this configuration attractive. And the olefins/polymers complex may be only the start. In a news release, Shell says it has “an array of long-term options to monetize natural gas. Extracting ethane and other natural gas liquids (to produce) petrochemicals is one of these options, which also include developing shipping solutions for LNG; proprietary gas-to-liquids technology to produce fuels, lubricants and chemicals; and gas-for-transport in markets focusing on heavy-duty vehicles, marine and rail transportation.”

The company is fully on board with the new gas paradigm in North America, says Marvin Odum, president of Shell Oil. Of the Marcellus cracker project, he says, “U.S. natural gas is abundant and affordable. Shell has the expertise and technology to responsibly develop this vital energy resource, including associated products such as polyethylene for the domestic market. With this investment, we would use feedstock from the Marcellus to produce chemicals for the region and create more American jobs. As an integrated oil and gas company, we are best-placed in the area to do this.”

Shell owns and operates four U.S. steam crackers and associated derivative plants at Deer Park, Tx., and Norco, La.

“Whether built by Shell or anyone else, a Marcellus cracker should be a strong commercial success,” offers IHS Chemical’s Barrasa. “In fact, in terms of security of supply and a lack of significant ethylene storage infrastructure in the region, you almost need two crackers.”

The situation in the Marcellus is “a classic trapped ethane problem,” observes Mark Eramo, vice president of chemical research and analysis at IHS Chemical. “It is the same thing we saw in Alberta in the 1980s and in Saudi Arabia in the past two decades. You can either build a cracker on site and ship the derivatives, or you can build a pipeline to transport the ethane. Both are viable.”

In the case of the Marcellus Shale, and now emerging activity in the wet-gas window of the Utica Shale in Ohio and Pennsylvania, it looks likely that both options may be played out eventually, Eramo adds.

Propylene And Butenes

As steam cracker feedslates have gotten lighter, the volume of co-product propylene (C3) and butylenes (C4) has decreased. The experts say North America has been structurally short of C4s for some time, and now is experiencing the same with C3s. In 2010, PetroLogistics brought on stream the world’s largest propane dehydrogenation unit on the Houston Ship Channel.

“Some people may have that thought that was crazy at the time,” recalls Chuck Carr, director of propylene studies at IHS Chemical. “But we now forecast about 150,000 bbl/d of propane demand is going to be added in North America by 2020. All of that is from the chemical industry, with the North American fuel market for propane forecast for minimal growth. Beyond domestic use, Enterprise and Targa Resources are adding propane export capabilities.”

The biggest and most recent move in propane is a plan by Dow Chemical to get into dehydrogenation. In January, Dow announced that it had selected the process technology company UOP, now part of Honeywell, to provide technology to produce propylene at Dow’s Freeport, Tx., complex–one of the largest chemical manufacturing sites in the world.

Dow reports that it will use UOP’s Oleflex™ technology in a new propane dehydrogenation unit to convert shale gas-derived propane to propylene. The facility will produce 750,000 metric tons annually of polymer-grade propylene, and is scheduled to come on stream in 2015. The company says the facility will be the first of its kind in the United States, and the largest single-train propane dehydrogenation plant in North America.

“There is a unique opportunity in today’s market where shale gas development is driving lower prices and greater availability of propane as a feedstock for petrochemicals,” Pete Piotrowski, UOP’s senior vice president for process technology and equipment, notes in a statement regarding its role in Dow’s Freeport plant.

The equation for butadiene is more complicated, says IHS Chemical’s Carr. “You need two steps, one from butane to a mixed butenes stream, and then one step splitting and converting to butadiene,” he says. “That is a lot of cats and dogs.”

He also notes that the short market on butadiene has been around for several years and that there is a constant ebb and flow on how best to supply end-use markets.

Honeywell is one of the licensors for methanol-to-olefins technology. Companies, notably France-headquartered Total, are considering such operations, according to published reports. Chinese companies are thought to be moving ahead with commercial operations. The rough calculation is that 2 million metric tons of methanol would produce 500,000 metric tons of olefins in a 50-50 mix of ethylene and propylene, according to industry analysts.

Some market observers indicate they are surprised that one of the simplest chemical conversions–methane to ammonia–has yet to gain a lift from the shale gas boom. The domestic market for ammonia fertilizer is 21 million metric tons, according to IHS Chemical, of which 7.5 million metric tons (36 percent) are imported. Johnson points out that there are also several idle ammonia plants, and to date, only one fertilizer company (CF Industries) has announced restarting a domestic ammonia train, but he says more can be expected to follow.

Different Global Game

Petrochemical companies look at their investments based on costs, cash generation and capital management, says Garrett Gee, director of chemical advisory services at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. “Shale gas represents a once-in-a-century change in the competitive balance worldwide,” he comments. “This is a major capital opportunity to play a global game very differently.”

He stresses that the full story is still unfolding, and that there will be plenty of midcourse corrections. “But the most important thing is that we now have an unprecedented supply of natural gas and natural gas liquids,” Gee says. “Even if the estimates of shale gas supply are off by half, it still represents a huge volume of light hydrocarbons. Even if liquefied natural gas exports of U.S.-produced gas go ahead full out, all that would be hard pressed to change the new dynamics in the North American gas market.”

Producers and analysts agree that firm floors and ceilings are forming in the natural gas market. According to Gee, one likely scenario is a floor in the range of $2.50 an Mcf equivalent at Henry Hub, based on supply and demand forecasts by the Energy Information Administration. At that price, he says, all discretionary production ceases, but there is still production under firm contracts to retain held-by-production acreage and associated gas from wet-gas and oil production operations. The top end, Gee projects, appears to be in the range of $5.50 an Mcf, a price level at which he suggests most dry gas basins would become cash flow positive.

On the NGLs side, the calculus is more complicated. Gee figures there are no fewer than six factors at play in decisions to build a Marcellus ethane cracker. “First, Marcellus drillers are hesitant to lock all available production into long-term contracts. Second, there really are limited NGL hedging options for ethane, but some for propane and butane,” he details. “There is obviously a lack of meaningful infrastructure in the region, but at the same time, ethylene demand is not growing significantly in North America in comparison to the forecasted supply.

“There also are other outlets, notably across the border at Sarnia", Gee goes on. “With a cracker located in the Marcellus region, industry participants can achieve lower costs in managing their respective supply chains,” he says. “Finally, there are some polymer and many converter companies in the region.”

Converters take polymer pellets and form them into either finished plastic products, or into component parts that go into other goods, including electronics and automobiles, Gee explains. By several estimates, two-thirds of the plastics converters in North America are within 500 miles of the Marcellus Shale play.

The American Chemistry Council has completed a study titled Shale Gas and New Petrochemicals Investment: Benefits for the Economy, Jobs and U.S. Manufacturing. It anticipates a $16.2 billion private investment over several years in new plant and equipment for manufacturing petrochemicals. That investment not only would create jobs and additional output in other sectors of the economy, but also would lead to a 25 percent increase in U.S. petrochemicals capacity and $32.9 billion in additional chemical industry output, the study estimates.

In addition to direct effects, the study forecasts indirect and induced effects from those added outputs would lead to an additional $50.6 billion gain elsewhere in the economy, and create more than 17,000 jobs directly in the chemical industry. Those positions would be knowledge-intensive, high-paying jobs, “the type of manufacturing jobs that policymakers would welcome in this economy,” the report states.

In addition to chemical-industry jobs, another 165,000 jobs would be created elsewhere in the economy from the investment in the chemical industry, totaling more than 182,000 jobs, the American Chemistry Council report continues. The jobs and output resulting from the investment would, in turn, lead to a gain in federal, state and local tax collections totaling $4.4 billion per year, or $43.9 billion over 10 years, the report says.

AFPM’s Cooper concurs with the long view. “Our members are thinking decades down the line. When we think of gas prices, we think globally. This is how we expect the market to play out: If our industry has the infrastructure in place, and the demand for our products grows, the natural gas and NGLs are going to be there for us,” he concludes. “Domestic oil and gas producers are going to continue to be able to supply us with the resources we need.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.