Oil Production

U.S. Oil Output Poised To Hit Historic High

WASHINGTON–Domestic crude oil production is forecast to reach an average of 9.9 million barrels a day in 2018, which would surpass the previous record of 9.6 million bbl/d set in 1970, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

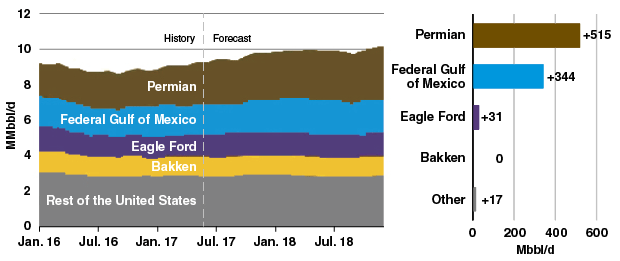

In its July Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO), the agency reported that total U.S. crude oil production was on track to average 9.3 million bbl/d this year, which would represent an increase of 500,000 bbl/d over 2016. EIA says most of the growth in U.S. oil production through the end of 2018 is forecast to come from tight rock formations in the Permian Basin as well deepwater fields in the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1).

By the end of next year, EIA projects that the Permian region will be producing 2.9 million bbl/d, accounting for nearly 30 percent of total domestic crude oil output. In June, EIA estimates that Permian operators produced 2.4 million bbl/d.

Covering some 53 million acres in West Texas and Southeast New Mexico, the Permian Basin contains several prolific conventional formations as well as multiple tight formations such as the Wolfcamp, Spraberry and Bone Spring in the Midland and Delaware sub-basins. “With the large geographic area of the Permian region and stacked plays, operators can continue to drill through several tight oil layers and increase production, even with sustained West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices below $50 a barrel,” the STEO states.

Based on Baker Hughes data, 366 of the 915 onshore rigs active in the lower-48 in June were operating in the Permian. EIA forecasts that the Permian rig count will fall slightly to 345 at the end of this year, but then begin moving upward to 370 by the end of 2018.

“In addition to responding to changes in (oil) price, increases in rig counts are also related to cash flow. In the Permian, operators have been able to maintain positive cash flow because of lower costs, higher productivity, and increased hedging activity by producers, many of whom have sold future production at prices higher than $50/bbl,” EIA points out. “Available cash flows could potentially contribute to the growth of rigs in this region despite relatively flat crude oil prices since December 2016.”

According to EIA, productivity as measured by new well oil production per rig decreased in the Permian in June for the 10th consecutive month. Output per rig is likely decreasing because operators are drilling more wells than they are completing, the agency notes, with the increasing inventory of drilled but uncompleted wells lowering overall output per rig.

“The trend of operators drilling more wells than they are completing does not have a clear cause, but a widening of the WTI-Midland crude oil price discount to WTI-Cushing since the beginning of 2017 suggests the possibility of some minor transportation constraints,” EIA comments. “Lags in well completion may also reflect implementation of strategies that drill more wells from a single pad with completion equipment not deployed until all wells are drilled.”

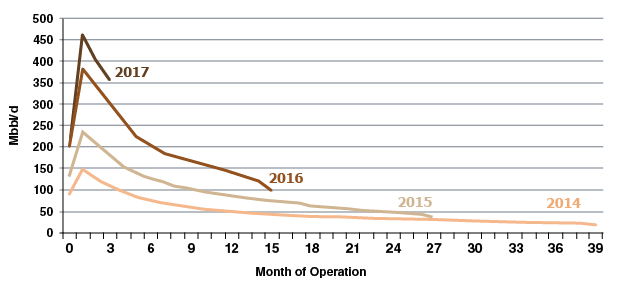

Average output per well shows that productivity based on initial production rates continues to increase in the Permian Basin (Figure 2). Year-to-date initial production based on average output per well is higher than the 2016 annual average, according to EIA. “Many operators are continuing to experiment with completion techniques to maximize output per well, suggesting the 2017 annual average initial production rate could continue to increase,” the agency says.

FIGURE 2

Permian Basin Average Production per Well

Note: 2017 is based on data through April. Other years represent annual averages.

Permian Production Hedges

According to the results of a study conducted by IHS Markit, the oil-weighted, Permian-focused companies it surveyed have 65 percent of their 2017 oil production hedged at an average price of $50/bbl and half of their 2017 gas production hedged at $3/Mcf. That compares with only 19 percent of oil and 29 percent of gas production hedged by an oil-weighted peer group of non-Permian producers.

“The different levels of hedging between the two oil-weighted subgroups of Permian versus non-Permian operators are reflected in the wide disparity of their production growth targets, and the difference is striking,” comments Paul O’Donnell, principal equity analyst at IHS Markit. “The median Permian (company) is expected to increase its oil production by 25 percent in 2017, as compared to those oil-weighted operators outside the Permian, which are anticipating a median decline of 1 percent in oil/liquids production.”

Overall, oil-weighted U.S. companies increased oil hedging from 22 percent to 34 percent since the third quarter 2016 data. “Hedging is still important, especially the more debt-laden companies, which are less likely to withstand sustained low prices or significant price fluctuations,” explains O’Donnell.

To support their aggressive production growth targets, the Permian group of operators already has hedged 25 percent of oil production at $51/bbl and 9 percent of gas at $3/Mcf. In contrast, O’Donnell says the non-Permian producer group is largely unhedged for oil, but also has 9 percent of its gas production hedged.

The Permian operators with the best downside protection should prices drop include Concho Resources, Parsley Energy and Laredo Petroleum, which have hedged prices above $50/bbl for both 2017 and 2018, according to O’Donnell. For Permian operators that have not yet hedged 2018 production, he adds that it would be a challenge to replicate their 2017 hedge positions given the relatively flat futures price curve.

Deepwater Fields Starting Up

In the Gulf of Mexico, EIA reports that eight new projects came online in 2016, allowing oil production in federal waters to set an annual high of 1.6 million bbl/d (surpassing the previous high set in 2009 by 44,000 bbl/d). Another seven projects are anticipated to come online by the end of 2018, increasing Gulf production to an average of 1.7 million bbl/d in 2017 and 1.9 million bbl/d in 2018.

The eight new fields starting production in 2016 were Noble Energy’s Gunflint in 6,138 feet of water, Anadarko’s Heidelberg in 5,271 feet of water, ExxonMobil’s Julia in 7,087 feet of water, BP’s Kodiak in 5,006 feet of water, Shell’s Stones in 9,556 feet of water, BP’s Thunderhorse South Expansion in 6,050 feet of water, Apache’s Wide Berth in 3,700 feet of water, and Anadarko’s Caesar/Tonga Phase II in 5,000 feet of water.

New field starts this year and next include LLOG’s Sun of Bluto 2 in 6,461 feet of water, Freeport McMoRan’s Horn Mountain Deep in 5,400 feet of water, Stone Energy’s Amethyst in 1,200 feet of water, BP’s Atlantis North in 7,128 feet of water, LLOG’s Otis in 3,800 feet of water, and the Hess-operated Stampede-Knotty Head and Stampede-Pony developments in 3,557 and 3,497 feet of water, respectively.

EIA points out that the 15 new field startups in 2016-18 were discovered as long ago as 1998. In fact, only three of the fields (Horn Mountain Deep, Amethyst and Otis) were discovered within the past five years. The time from discovery to first production averaged 10 years for the eight fields that commenced production in 2016, and averages 8.5 years for the seven fields scheduled to begin production this year and next.

“Because of the time needed to complete large offshore projects, oil production in the Gulf is less sensitive to short-term oil price movements than onshore production. However, the number of development and exploratory wells has fallen each year since 2012. The number of rotary rigs operating in the GOM decreased from an average of 55 in 2014 to 22 in 2016.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.